|

As part of their responsibilities of leading the organisation, strategic leaders are responsible for leading change. This article investigated the application of the strategic leadership of change within the church context. A Straussian approach to the grounded theory method was used to generate a substantive grounded theory of organisational change and leadership, particularly focusing on the manifestation and management of organisation inertia in churches within South Africa that were transitioning from a programme based to a cell based church design. This article reported on one aspect of this study and focused on the patterns of leadership roles. It further distinguished between effective and ineffective leadership patterns that either enhanced or compromised the credibility of the leader and by implication, affected the success of the change intervention. The results of the study were discussed from the perspective of social capital theory, thereby contributing to understanding the role of strategic leaders in building social capital within the context of organisation change.

The resource–based view of organisations focuses on the unique internal characteristics (such as strategic leadership) or ‘inner growth engines’ of an organisation that account for its success (Hoskisson, Hitt, Wan & Yiu 1999). According to Boal and Hooijberg (2000):strategic theories of leadership are concerned with leadership ‘of’ organizations … and are marked by a concern for the evolution of the organization as a whole, including its changing aims and capabilities… (Boal & Hooijberg 2000:516) A key element identified in bringing about successful organisational change, is for leaders of change to be able to reduce resistance to change (Kinnear & Roodt 1998). Kinnear and Roodt (1998:44) refer to ‘the resistance of an organization to make transitions and its inability to quickly and effectively react to change’, as organisational inertia and argue that this term incorporates all related concepts describing lethargic responses of organisations to change. Research using the grounded theory method (Strauss & Corbin 1990) was conducted to generate a theory that explained the manifestation and management of resistance to change, or organisational inertia, in churches. All of the churches studied were undergoing a particular kind of change; transitioning from a programme-based to a cell-based model. Pursuing the goals of this article ultimately generated a theory incorporating three areas: firstly, a generic, composite, descriptive account of the change process, secondly, the construction of the concept of a sense of community and finally, leadership activities and patterns that were both engaged in the change process and simultaneously influenced various dimensions of the sense of community. This article focuses on the third area, the leadership patterns and activities.

In this article, a Straussian approach (Strauss & Corbin 1990) to the grounded theory method was followed. The intention of grounded theory is to generate new theory (Glaser & Strauss 1967; Strauss & Corbin 1990). The methodology spans the process of systematically collecting data through to the development of a ‘multivariate conceptual theory’ (Glaser 1999:836). The classical formulation of grounded theory methodology, as developed by Glaser and Strauss (1967), rests upon two interrelated procedures, namely theoretical sampling and constant comparison. Theoretical sampling is a process of data collection that occurs concurrently with data coding and analysis and is dictated by the emerging theory (Glaser & Strauss 1967). A sample of incidents was gathered from 38 in-depth interviews, conducted with ministers who were leading churches of various backgrounds, sizes and denominations in four South African provinces. These interviews explored the interviewees’ experiences in implementing change, including the problems encountered and how these were resolved. Initially, purposive sampling followed by theoretical sampling (Glaser & Strauss 1967) was used to identify suitable interviewees. The interviews were selectively transcribed and analysed. The interview data was analysed using open coding and constant comparison (Strauss & Corbin 1990) to generate categories. Open coding is the ‘process of breaking down, examining, comparing, conceptualising, and categorizing data’ (Strauss & Corbin 1990:61). Constant comparison involves comparing an incident with previous ones and then coding it into as many categories as possible. As the number of incidents grows, comparing of a new incident to each category of incidents would aid in generating the properties of the categories. At this point, through constant comparison and continued questioning, codes or categories are raised to a conceptual level through the specification of the conditions under which the concept occurs, through providing explanations for the occurrence and by making predictions of when it will occur. This forms the basis of the theory that emerges. Through further axial and selective coding (Strauss & Corbin 1990) a grounded theory was developed.

|

Essential research findings

|

|

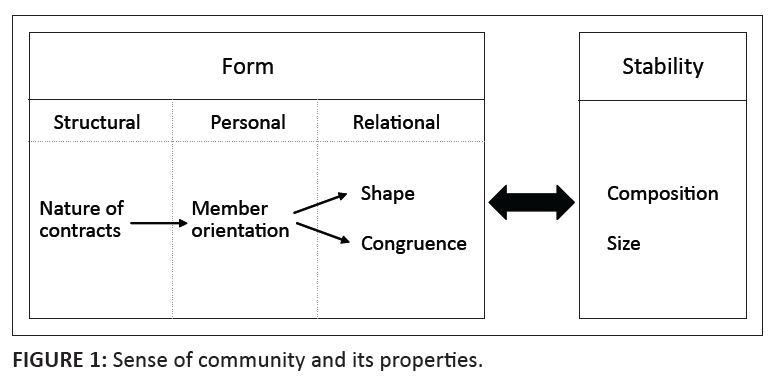

During the process of change where churches transitioned to a cell church design, the central characteristic being affected was the sense of community of the church. This concept of sense of community was

defined as a sense of collective-identity, -purpose and -belonging amongst people who pray for, love, serve, develop and support each other in ‘extended family’ relationships

(Pearse & Smith 2007:161). Sense of community is multi-faceted and was constructed to consist of two main properties, namely its form and the stability of this form. The construction

of the sense of community concept is illustrated in Figure 1.

The form of community is the dominant property of community and can be described in terms of its sub-properties. The first sub-property of form reflects the structural aspects of community and addresses questions such as: ‘who is in community, at both the collective and individual levels?’, ‘how do they come into and maintain contact with one another?’ and ‘what is the qualitative nature of these contacts?’ The second sub-property, member orientation, refers to the orientation of the individual members with respect to their focus, their perceived role in the church and the degree of concern shown about the role of the church in society. This can be thought of as the mindset that develops out of the interactions that the structural aspects promote. Thirdly, community has a shape. This shape has depth, which is characterised by the degree of intimacy and genuineness of relationships. It also has breadth, a quantitative measure of how many people (or groups) are part of the community. The shape of community may also be seen to exist at a number of levels. For example, at one level a sense of community may exist amongst the top leadership group of the church, whilst at another level it is reflected within a single small group. This final sub-property of the form of community is referred to as its degree of congruence. That is, the degree to which community retains a coherent characteristic form across the organisation and at different levels. Stability of community is a secondary property of sense of community, reflecting the dynamic nature of the sense of community over time and can be described in terms of changes in member composition and changes in membership size. Stability of community is therefore related to the degree of movement of people into and out of community. In considering the transition of churches in this study, it was evident that the change process had direct and indirect effects on various properties of the sense of community. Before initiating the transition, the leadership core of the church described how they had become increasingly aware of deficits in the church’s sense of community, most noticeably its weakness in not being relevant to or having an impact on society and the lack of breadth as expressed in evangelistic activity. This translated into concerns about the lack of growth in membership size, not for its own sake, but as an indicator of carrying out their Biblical mandate to make disciples. Whilst leaders were concerned that the church members were too internally focused, they were also concerned about the relatively impersonal nature of the contacts that were created within the church through its programmes; therefore, both the current state of the church as well as the ideal state of the church post-transition could be described in

terms of the properties of sense of community. It is not surprising then, that once the change was initiated it began to affect the state of the sense of community. This, in turn, gave rise to resistance to change or organisational inertia in various forms.

|

FIGURE 1: Sense of community and its properties.

|

|

Part of the selective coding process of grounded theory is re-arranging the data according to patterns that are being observed, so that the specificity of the theory can be enhanced, or the conditions of its occurrence specified (Strauss & Corbin 1990). In this section, the interaction of leadership patterns with sense of community is developed in the context of the cell-church transition. Furthermore, the leadership activities underpinning these patterns are described, followed by a description of the implications for the credibility of the leadership. The effective and ineffective leadership patterns respectively enhanced or compromised the credibility of the leader and by implication, affected the success of the change intervention.

Patterns of leadership action

In examining the actions of leaders, three effective, interacting and interrelated patterns of leadership action emerged. These patterns have been referred to as the freewheeler, the focused-pioneer and the reflexive-accommodator pattern. Corresponding to each of these effective patterns are three ineffective patterns that arise when elements of each of the corresponding effective patterns are overemphasised. These ineffective leadership patterns have been labelled the static non-leader, the rigid combatant and the popular people pleaser pattern, respectively. Figure 2 illustrates the relationship between the various leadership patterns and sense of community. These leadership patterns should not simply be interpreted as leadership styles that are ascribed to various leaders. Rather, they are patterns arising because of the interaction between leaders and their context over a particular period of time. That is, a series of incidents or events and a leader’s activities in response thereto, usually typified a pattern. To further develop this point, there were times when the same individual displayed different patterns in different churches they had ministered in. There are also cases where the same leader in the same church displayed a variety of patterns at different times. Furthermore, it is proposed that effective leadership entails balancing the three effective patterns so as to avoid their ineffective counterparts. In other words, the three patterns are interrelated and the application of one pattern prevents the emergence of the ineffective counterpart of another. The organisational context that leaders confronted when transitioning the church varied in terms of the level of organisational inertia that was manifested in response to modifications being made to the sense of community. That is, high organisational inertia was prevalent when there was much in the organisation that needed to be changed in order to bring it in to line with the desired state and in doing so, the existing sense of community was greatly altered. In this instance, the organisation could be thought of as needing to be turned around, as its velocity is currently propelling it in the ‘wrong’ direction. In contrast, instances of low inertia arose when the organisation was already moving in the desired direction. Similarly, when leaders tried to change the direction of a church, such as in transitioning from a programme-based model to a cell-based model, successfully negotiating this change involved on the one hand steering the church in the new direction and allaying member’s concerns on the other. The leader had to manage the delicate balance between pushing ahead with change and thereby compelling the church to fulfil its perceived purpose and slowing down the pace of change to accommodate members’ needs. Accordingly, when the focused pioneer pattern produced high levels of organisation inertia, the reflexive accommodating pattern was needed to balance it out and allay members’ concerns. Excessive forcing of change is ineffective leadership as described in the rigid combatant pattern, whilst accommodating concerns at the expense of fulfilling the purpose of the church, is also ineffective, as described in the popular people pleaser pattern. When organisational inertia was low, this was because the organisation was already moving in the direction of desired change. The current velocity simply needed to be maintained. This is what the freewheeler pattern entails. However, if there is no leadership influence, the velocity of change is lost. According to Newton’s law, this is because there are forces, such as friction and gravity, working against the current motion. Similarly, organisations can lose their velocity in the absence of active leadership. This inactive leadership is expressed in the static non-leadership pattern. Leaders needed to keep reminding their followers of the direction that had been set and keep exercising influence to ensure that the member orientation properties of sense of community continued to mature in the desired direction. If the leader failed to do this, there was a tendency for members to pursue their disparate individual needs or preferred directions.

Leadership activities

In the research, three sets of leadership activities were identified, namely searching activities, influencing activities and configuring activities. Searching activities are concerned with collecting information that will assist in clarifying, setting and confirming the purpose and direction of the local church. Influencing activities are primarily focused on changing the ideas, beliefs, values and behaviour of people. Some of these activities are intentionally influencing, or instrumental; whilst others are relational and enhance the influence of the leader as a result of the stronger relationship that is being developed. Configuring activities involve designing, structuring and restructuring the socio-technical systems and structures of the local church. The linkage between the sense of community and the various leadership patterns can be understood more fully by examining the effects of the various leadership activities that characterise each of the patterns of leadership, on the sense of community.Searching activities can be construed as seeking to hear the ‘voice of God’, as opposed to seeking to hear the voice of the people. The effective patterns try to manage the tensions between these two voices, with the reflexive accommodator placing more emphasis on ‘trialogue’. Looking at the ineffective styles, the static non-leader tends to ignore the voices, whilst the popular people pleaser harkens to the voice of the people. Finally, the rigid combatant, in believing to have heard the ‘voice of God’, is deaf to other voices. Configuring activities are pervasive within the focused pioneer pattern. Configuring activities incorporate composing, as well as developing systems and procedures. In composing the organisation, leaders create and/or remove opportunities for church members to interact. Thus, the structural nature of contacts within the church is affected. As this is the foundation for the other dimensions and sub-dimensions of sense of community, these configuring activities may have broad-based implications for the form and stability of the sense of community in the church. Depending on their nature, developing systems and procedures may also impact the form of community. For example, some of the training systems adopted as part of the church transition are designed to change the role of members so that they become service-oriented producers. Influencing activities are divided into two clusters, namely instrumental and relational influence. Focused pioneers typically used instrumental influence to promote their change agenda. One of the intentions behind utilising instrumental influence was to alter the member orientation component of sense of community. For example, preaching on the vision and values of the church or modelling appropriate behaviour encouraged people to become more active in the church and to be more concerned about others than themselves. Instrumental influence also advances a new shape of community. For instance, as people were encouraged and shown how to reach out to others in the church and outside the church, the depth and breadth of sense of community was shaped accordingly. Leaders who demonstrated relational influence developed closer relationships with people. This had the effect of increasing the depth of sense of community by promoting intimacy and genuineness at a number of levels within the church, most notably amongst current and potential leadership groupings. Relational influence was usually the type of leadership activity that reflexive accommodators first resorted to. Table 1 summarises the linkage between leadership patterns, leadership activities and sense of community that has been developed here. The table ‘quantifies’ the prevalence of a particular set of leadership activities within each leadership pattern. These need to be read in conjunction with the qualitative characteristics described above.

|

TABLE 1: Relationship between leadership activities and leadership patterns.

|

Leadership patterns and leadership credibility

The findings of the research suggested that as the process of change was embarked upon, the overreliance on ineffective patterns of leadership adversely affected the credibility of the leader, whilst the effective handling of the change initiative enhanced their credibility. Those leaders who drove the change process hard tended to begin to adopt the rigid combatant leadership pattern, which led to a decline in their credibility. On the other hand, with the popular pleaser or static non-leader patterns, where there was a loss or lack of momentum of the change initiative, this was equally damaging to leader credibility. This suggests that varying the pace of change affected leader credibility. Without credibility, the influence of the leader was undermined and the ability to continue with a change initiative compromised. In some situations, credibility of leadership was compromised to the point of separation of leader and followers. Whilst some of these departing followers may well have been laggards, the

leader’s actions had certainly contributed to their departure. Where the leader succeeded in maintaining an acceptable pace of change, their credibility was enhanced. This was more typically associated with the effective leadership patterns.

In this article, three effective patterns of leadership have been described along with their ineffective counterparts. These patterns were characterised by a particular combination of leadership activities, which have also been described. It was further noted that effective leadership of change involves balancing these three effective patterns over time. In research investigating radical change, Huy (2002) made a similar discovery about the importance of balancing, with the focus in that study being on emotional balancing. On the other hand, a lack of flexibility, or persistence in pursuing only one pattern of leadership for an extended period of time meant that the leader failed to achieve a balance and thereby produced an ineffective pattern. This infectiveness of leadership undermined the perceived credibility of the leader, as their actions harmed the sense of community, which in turn adversely affected the momentum of the change initiative. Given the resonance of the construct sense of community with the literature on social capital, the results of the article are discussed from the perspective of social capital theory and highlight the role of leadership in either developing organisational social capital or eroding it.

Organisational social capital

The concept of social capital has been applied widely (Leana & van Buuren 1999), but of particular interest here is its applicability to the organisational level, or in organisational social capital (OSC). Leana and Van Buuren (1999) define OSC as:

a resource reflecting the character of social relations within the firm … realized through members’ levels of collective goal orientation and shared trust, which create value by facilitating successful collective action. (Leana &Van Buuren 1999:538)Furthermore, in the light of the grounded theory that has been developed, with sense of community central to it, the spotlight on OSC can be narrowed down even more, to focus primarily on internal social capital, the ties an actor maintains within a collective, rather than with outsiders (Adler & Kwon 2002; Hitt & Ireland 2002). Internal social capital has to do with ‘the relationships between strategic leaders and those whom they lead as well as relationships across all of the organization’s work units’ (Hitt & Ireland 2002:5). Hitt and Ireland (2002) describe the process used by strategic leaders to manage human and social capital resources in companies in order to attain a competitive advantage. Whilst recognising the differences in the organisational context and purpose between churches and companies, the resource management process described by these authors provides a useful framework within which to look at the management of the church’s social capital. This continuous process consists of three interdependent components, namely resource inventory, resource bundling and resource leveraging.

Resource inventory

Resource inventory consists of three continuous and interdependent stages that are not necessarily sequential; namely resource evaluation, resource shedding and adding resources (Sirmon & Hitt 2003:344–348). Analogous to raw material inventory, resource evaluation involves determining current levels of social capital, recognising both strengths and deficiencies, including peoples’ ability to learn and develop new capabilities (Hitt & Ireland 2002:7–8). This evaluation needs to incorporate individual resource stocks, as well as the quality of relationships (Hitt & Ireland 2002). For Kay (1993) the value of social capital (what he refers to as architecture) lies in its capacity for knowledge creation, flexibility and information exchange.There are indications that part of the dissatisfaction that leaders experienced and that prompted them to search for a new model by which to lead the church, was their recognition that the social capital potential that was embedded in church relationships was not being realised. However, during their search activities, there was little evidence of leaders contemplating the capacity of their members to learn and develop the capabilities that were required to transition successfully. At the organisational level, the overall health of the church and its readiness for change was considered in some instances, but not the learning capacity of the individual members. This is an aspect that may require more careful consideration prior to embarking upon future transitions. An area that was sometimes given more thought was an ongoing assessment of the quality of relationships, those that the leader had with the members especially, but also those between members. It would seem that a rigid combatant pattern of leadership was particularly weak in this area, whilst it was the reflexive accommodator pattern’s strength. A second stage in the resource inventory component is resource shedding. Given the opportunity costs of maintaining and leveraging resources, it is often advisable to shed resources of low value that are not contributing to competitive advantage (Sirmon & Hitt 2003). This is not an easy thing to do in a family business setting, where it may, for example, involve releasing a family member from the business. Emotional ties, nostalgia and escalation of commitment have to be reckoned with, but failure to do so can lead to inertia (Sirmon & Hitt 2003). In the case of the churches investigated, those configuring activities of leaders that involved closing down particular church programmes, as well as some of the instrumental influence actions that overlooked the relational needs of members, can be understood as forms of resource shedding. These activities are particularly prevalent in the focused pioneer and rigid combatant patterns. The opportunity costs of such activities were also evident here. Leaders who maintained and supported programmes may have been popular with those involved with them, but also recognised that their continuation contributed to inertia. On the other hand, closure of programmes sometimes proved to be very difficult for leaders and traumatic for participants. The third stage of the resource inventory component involves adding resources ‘that can be integrated to create resource bundles that are valuable, rare, difficult to imitate, and non-substitutable, and that can be leveraged by a strategy’ (Sirmon & Hitt 2003:348). Family firms often have deficiencies in human capital that they need to address. There are a number of options here, such as (Sirmon & Hitt 2003:349–350): • recruiting heterogeneous human capital from outside the firm and utilising the existing social capital to facilitate its integration

• forming alliances

• developing internal resources

• learning from failure. In considering the cell-church transition, this scenario of human capital deficiencies can firstly be translated into the situation where there is the appointment of new leaders to promote, develop, or manage the cell-church model. This was only feasible in larger churches, where often, someone was appointed to assist the senior minister by administering the cell system. In smaller churches, additional employed staff could not be supported financially and so this was less likely. One possibility is that a successor to the current leader be appointed, but most often it was the current leader who was instrumental to driving this transition. In reality, churches struggled to develop their human capital base through new appointments and rather resorted to developing the existing human capital through configuring training and development activities. Where search activities were prevalent, the arrangement and development of these training activities were often facilitated by alliances with other churches in

the local fraternal, or denomination, through conference attendance or by using the services of training consultants. This was particularly evident in the reflexive accommodator pattern. Reflexivity was also evident when leaders adapted their leadership patterns through learning from their own mistakes and those of others, particularly if their credibility levels were being eroded.

Resource bundling

The resource bundling and leveraging components follow on from the resource inventory component (Sirmon & Hitt 2003). These components involve configuring resources into bundles, and then using these bundles ‘to formulate a strategy that exploits opportunities and creates a competitive advantage. In this way, managers leverage the firm’s resources to create wealth.’ (Sirmon & Hitt 2003:350). The configuring of resources often entails establishing integrative and coordinating mechanisms to link ‘silos’, requiring leaders to possess co-ordinating and persuasive skills so that groups are not only linked up, but also co-operative (Sirmon & Hitt 2003). Integrating human capital through coordination also makes use of the social capital of the group and leader (Hitt & Ireland 2002). Within the churches, resource bundling was evident in the configuring and relational influence activities of leaders. Configuring new structures to support the cell church transition

created new types of interactions between members that in turn lay the foundation for the bundling of new social capital resources. When this was combined with relational influence, trust was cultivated, further strengthening the social capital. This example highlights the delicate balance required between the focused pioneer and reflexive accommodator patterns, each of which places a premium on one of these sets of activities.

Leveraging resources

Leveraging resources involves using bundled resources to pursue strategic ends. Adler and Kwon (2002:32) suggest that social capital is only of value to an organisation to the extent that it is contributing to its objectives (task contingent) and valued by the surrounding environment (symbolically contingent). Task and symbolic contingencies are primarily the responsibility of the strategic leader. Hitt and Ireland (2002:9–10) describe the process of leveraging through leadership as requiring leaders to be facilitative, rather than controlling of members’ activities: • learning, absorbing and diffusing new knowledge

• shaping and structuring co-operative relationships

• using relational skills to build relationships with others

• essentially, building a collaborative mindset in the organisation. They propose a number of ways in which strategic leaders could build internal social capital, two of which were evident in this study. Firstly, leaders need to engage in building and utilising a team ‘as a means of developing effective, collaborative relationships.’ That is to say, there is a recognition that they cannot succeed on their own. Several church leaders who were interviewed highlighted the strength and unity of the leadership team as a critical factor responsible for the success of the church transition. The sense of community that was desired in the church had to first be reflected in the relationships at this level. Secondly, effective relationships within a team will arise from the engendering of a climate of trust within the group and from the leaders selectively showing their weaknesses or humanness. It is largely the form that day-to-day interaction takes that will determine the quality of relationships. Examining leadership actions in this study, particularly with the cell group leaders, relational influence activities such as validating others, befriending them, supporting others and accommodating their needs, promoted effective relationships.

Social capital and leadership

The resource–based view of organisations focuses on, inter alia, strategic leadership as a resource within an organisation that accounts for its success (Hoskisson et al. 1999). Similarly, organisational social capital would constitute a resource. This article has examined the role of strategic leadership in mobilising organisational social capital so as to bring about organisational change. In this case, examining churches that were undergoing the cell church transition, their leaders needed to first recognise the social capital potential that was embedded in church relationships, which had created a sense of community and that the change initiatives and their associated leadership actions had the potential to shed or build this resource. Secondly, leaders needed to configure the social capital resources so that groups were linked up and cooperative, thereby building a new sense of community. Thirdly, strategic leaders leveraged resources in order to support the intended change,

namely the transition to a cell based church. This also had the effect of reshaping the sense of community. The research further illustrated the complex challenge that strategic leaders faced in mobilising social capital had highlighted the importance of maintaining a balanced pattern of effective leadership.

This article has examined the way in which church leaders have tried to implement change and has focused particularly on leadership activities and patterns of leadership, noting the effect of these on the leader’s credibility. It has provided insight into some of the social aspects related to leading change and alerts leaders to both the potential and challenge of mobilising an organisation’s social capital towards organisational purposes.Building on the work of Hitt and others, who explain the role of strategic leaders in developing competitive advantage through advancing social capital, this article extends the literature on internal organisational social capital into the domain of church organisations and their leading of the cell church transition. In doing so, this article contributes to understanding the role of strategic leaders in building social capital, particularly as it relates to leading organisation change. Glaser and Strauss (1967) distinguished between substantive (or local) theories and formal (or general) theories, indicating that a substantive theory could be developed into a formal theory. Thus, substantive and formal theories differ in terms of level of generality and ideally, a formal theory should be developed from substantive theory (Glaser & Strauss 1967). It is therefore recommended that this contribution can be developed through further research that examines other forms of change and which investigates a wide range of organisation contexts, so as to advance towards the development of a formal theory.

Feedback from anonymous reviewers of this conference is acknowledged and appreciated.

Adler, P.S. & Kwon, S., 2002, ‘Social capital: Prospects for a new concept’, Academy of Management Review 27(1), 17–40.

doi:10.2307/4134367Boal, K.B. & Hooijberg, R., 2000, ‘Strategic leadership research: Moving on’, Leadership Quarterly 11(4), 515–549.

doi:10.1016/S1048-9843(00)00057-6 Glaser, B.G., 1999, ‘Keynote address from the Fourth Annual Qualitative Health Research Conference’, Qualitative Health Research 9(6), 836–845.

doi:10.1177/104973299129122199 Glaser, B.G. & Strauss, A.L., 1967, The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research, Aldine Atherton, Chicago, IL. Hitt, M.A. & Ireland, R.D., 2002, ‘The essence of strategic leadership: Managing human and social capital’, The Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies 9(1), 3–14.

doi:10.1177/107179190200900101 Hoskisson, R.E., Hitt, M.A., Wan, W.P. & Yiu, D., 1999, ‘Theory and research in strategic management: Swings of a pendulum’, Journal of Management 25(3), 417–456.

doi:10.1177/014920639902500307 Huy, Q., 2002, ‘Emotional balancing of organizational continuity and radical change: The contribution of middle managers’, Administrative Science Quarterly 47, 31–69.

doi:10.2307/3094890 Kay, J., 1993, Foundations of corporate success: How business strategies add value, Oxford University Press, Oxford. Kinnear, C. & Roodt, G., 1998, ‘The development of an instrument for measuring organisational inertia’, Journal of Industrial Psychology 24(2), 44–54. Leana, C.R. & van Buren, H.J., 1999, ‘Organizational social capital and employment practices’, Academy of Management Review 24(3), 538–555.

doi:10.2307/259141 Pearse, N.J. & Smith, C.K.O., 2007, ‘Sense of community: An explanation of organizational inertia in cell church transitions’, Practical Theology in SA 22(2), 158–177. Sirmon, D.G. & Hitt, M.A., 2003, ‘Managing resources: Linking unique resources, management, and wealth creation in family firms’, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 27(4), 339–358.

doi:10.1111/1540-8520.t01-1-00013 Strauss, A. & Corbin, J., 1990, Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques, Sage Publications, Newbury Park, CA.

|