|

This article explored a methodology to construct the economic–historic context of the addressees of 1 Peter, which could serve as

basis for an economic interpretation of 1 Peter and other New Testament books. After discussing 1 Peter as letter, external sources were

used to construct the economic–historic context of the addressees of 1 Peter. This construction was then refined utilising the letter

itself, by identifying, categorising and interpreting the economically relevant portions of 1 Peter. Finally, the economic–historic

context of the addressees of 1 Peter was concluded and the method summarised.

Various scholars have made important contributions to some of the economic issues in the New Testament and to the history of early Christianity in

relation to the ancient economy. These treatments, however, have tended to be isolated studies focused on particular questions.1

Furthermore, very few of these investigations have been undertaken from the standpoint of the economic histories2 of Greece and

Rome or informed by economic theory in the Graeco-Roman world. In short, the economies and economic theories of antiquity have never been

related to the history of early Christianity in any kind of comprehensive, systematic way.3 Recently, however, an important volume

edited by Bruce Longenecker and Kelly Liebengood was published: Engaging economics: New Testament scenarios and early Christian reception

(Longenecker & Liebengood 2009). Two contributions in this volume are relevant to the present article, ’Methodological issues in using

economic evidence in interpretation of early Christian texts’ (Oakes 2009:7–34) and ’Aliens and strangers? The socio-economic

location of the addressees of 1 Peter’ (Horrell 2009:176–204).

This article wants to contribute towards a delineation of the relationship between early Christianity and the ancient economy by exploring a

method for constructing the economic–historic context of the addressees of 1 Peter. This could then serve as basis for an interpretation

of 1 Peter within this economic–historic context.4

I approach the topic ‘economy’5 as comprehensively as possible, looking at all relevant data, whether dealing with individual

personal finance or with the economies of the relevant towns and countries as far as such data is available. By beginning with the relevant ancient

economies themselves and viewing the ’economy’ broadly, I want to contribute towards not only gaining a better understanding of the Graeco-

Roman world, but also to ground the economic study of 1 Peter securely within its ancient socio-historical context.

To interpret 1 Peter within its economic–historic context, it is necessary to construct this context. Linking on to the definition of the task

of economic history by Morris, Saller and Scheidel (2007:1), I view the task of constructing the economic–historic context of 1 Peter to explain

the structure and performance of economics in the area where the addressees of 1 Peter lived. To explain the ’structure’ means to theorise

about the characteristics of society, which are purported to be the basic determinants of performance (like political and economic institutions,

technology, demography and ideology of a society), with the potential of refutability. Explaining the ’performance’ entails hypothesising

about the typical concerns of economists (like how much is produced, the distribution of costs and benefits and the stability of production), with the

potential of refutability.

I hope to build on 20th century advances in understanding institutions and ideology by attempting to clarify the relationships between structure and

performance. Morris, Saller and Scheidel (2007:7) see this endeavour as the second of three main challenges facing Graeco-Roman economic historians

in the early 21st century.6 This requires continued engagement with the social sciences.

In the following, I discuss 1 Peter as letter. I then construct the economic–historic context of the addressees of the letter utilising external sources

afterwards. Next, this construction is refined utilising 1 Peter itself: the economically relevant portions of 1 Peter is identified, categorised

and interpreted. Finally the economic–historic context of the addressees of 1 Peter is concluded and the method used is evaluated.

It is, however, necessary to first share my view of 1 Peter as letter, because this impacts on the spatial and temporal issues involved in constructing

the economic–historic context of the addressees of 1 Peter.

The date and authorship of 1 Peter

Together with quite a number of recent scholars, I view 1 Peter as a genuine letter and that it is, like 2 Peter, Galatians, Ephesians, James and

Jude, a circular letter (Achtemeier 1996:61–62; Aune 1987:159; Doty 1973:18; Elliott 1986:11; Goppelt 1978:45; ThurÈn 1989:93–94). 1

Peter also exhibits definite characteristics of the contemporary Jewish diaspora letter, as do the other New Testament circular letters (Aune

1987:185; Schnider & Stenger 1987:24–38).

Research has given no persuasive arguments that Peter the apostle could not have written the letter, having dispatched it from Rome.7

Therefore, along with a number of scholars (Selwyn 1952:27–33; ThurÈn 1989:25–28; Van Unnik 1980a:80; Guthrie 1970:792–796), I

take the self identification of the author as a matter of fact. This viewpoint implies that the letter is to be dated before 70 AD.8

The argument of 1 Peter

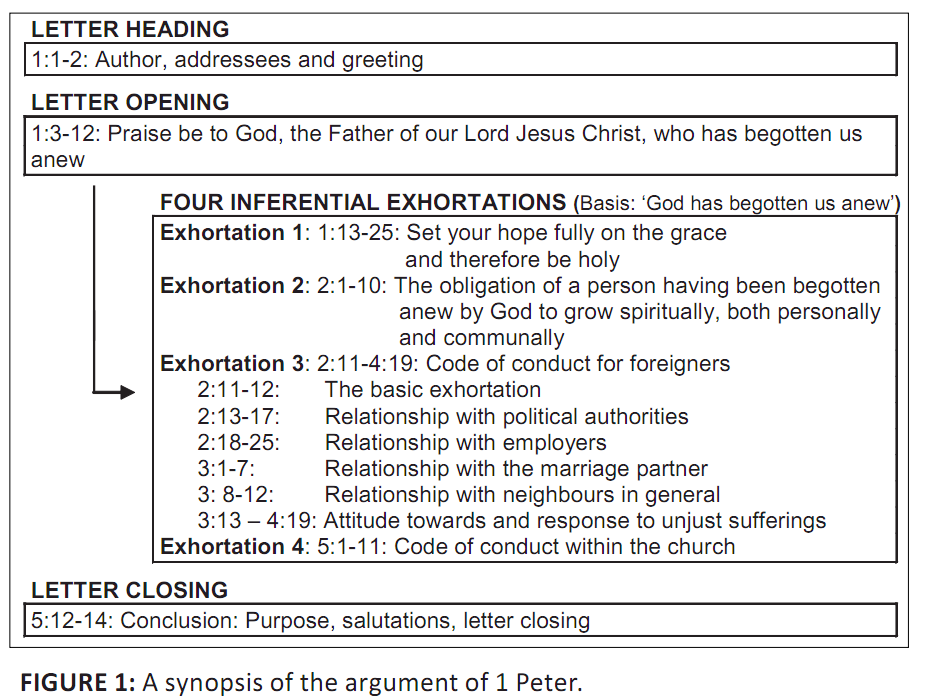

As frame of reference for the identification and interpretation of the relevant portions in 1 Peter, I accept the argument of this letter proposed

Van Rensburg (2006:481–488). According to this interpretation, the basic statement in 1 Peter is that the Father has begotten anew the first

readers (πατὴρ τοῦ κυρίου ἡμῶν Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ … ἀναγεννήσας ἡμᾶς

[‘Father of our Lord Jesus Christ … who has begotten us anew’], 1:3) (1:3–12). This statement functions

as the basis for four inferences that are given as four exhortations:

• set your hope fully on the grace and therefore be holy (1:13–25)

• the obligation of a ’new’ child of God to grow individually, as well as together with fellow-believers (2:1–10)

• code of conduct for πάροικοι [resident foreigners] and

παρεπίδημοι [visiting foreigners] (2:11–4:19)

• code of conduct within the church (5:1–11).

This view of the argument of 1 Peter and specifically the coherence between the letter opening (1:3–12) and the body of the letter can be

represented in Figure 1.

|

FIGURE 1: A synopsis of the argument of 1 Peter.

|

|

The section 1 Peter 3:13–4:19 (Attitude towards and response to unjust sufferings) covers a large portion of the letter. Therefore it is

necessary also to give my interpretation of the inter-relationship of the subsections of this part of the letter:

• In 3:13–17, the third exhortation (2:11–12) is applied to the attitude towards and response to unjust suffering, stating

inter alia that only Christ should be revered as Lord.

• The section 3:18–22 gives the reason for revering only Christ as Lord, pointing to the fact that Christ is in the position of authority

after all powers had been subjugated to him.

• Christ’s position of authority, however, has a consequence for the way the readers should view their suffering (4:1–7a). The

addressees are also assured that their suffering will not last forever, because the time when Christ will judge the living and the dead is near.

• In 4:7b–11, the addressees are exhorted to a specific lifestyle as a consequence of the statement that the end of all things are near.

• The final section, 4:12–19, summarises the whole of 3:13–4:11 by indicating how the addressees should view their unjust suffering

and how they should respond to it.

This interpretation of the argument of 3:13–4:19 can be represented in Figure 2.

Having given my interpretation of the argument of 1 Peter, I will now, in the following section, construct the economic–historic context of the addressees.

|

The Economic–Historic context of 1 Peter Constructed from External Sources

|

|

The economic–historic context is constructed in a two-step process by utilising first sources other than 1 Peter and then the text of 1 Peter itself.

To begin with, I focus on relevant economic tendencies in the 1st century Graeco-Roman world in general and afterwards construct the structure and performance

of economics in the area where the addressees of 1 Peter lived.

Economic tendencies in the 1st century Graeco-Roman world

In the 1st century, the word οἰκονομία [household management] did not

refer to the study of how nations and societies produced, distributed and consumed goods, but rather designated the management

of the private household (οἶκος [household]),9 the basic unit of production as well

as consumption in the Graeco-Roman world (Saller 2007:87). Ancient households (typically comprising a two-generation nuclear family,

free and unfree dependants, slaves, animals, land and other property; see Saller 2007:91–92) endeavoured to be as self-sufficient

as possible (Cartledge 1996). In a similar fashion, so did most cities and nations, but the vicissitudes of life (for example weather,

war and illness), as well as the opportunities created by trade guaranteed that individuals, communities and nations were dependent on

goods and services from external sources to various degrees.

Some classical scholars assert that relevant economic thought did not arise until the Enlightenment, as early economic thought was based on

metaphysical principles that are incommensurate with contemporary dominant economic theories such as neo-classical economics (Meikle 1995;

Finley 1970). However, several ancient Greek and Roman thinkers, especially Aristotle and Xenophon, made various economic observations.

Many other Greek writings also show understanding of sophisticated economic concepts.

It is acknowledged that, in dealing with issues of exchange and accumulation, ancient economic theory gave greater attention to ethical concerns

than to technical considerations. In addition, it did not share the frequent present day assumption about the autonomy of economics (Nussbaum 1996).

The economies of ancient Greece and Rome, as well as the economies of the most important Hellenistic kingdoms, were not only diverse but changed

over time. Major shifts from exclusively rural and village-based agricultural economies to those that included port cities, large mining operations

and major urban centres, populated with many transient workers, foreigners and immigrants took place.

Trade and commerce in the Roman world from the late 1st century BC until the 4th century AD underwent some fundamental alterations, yet there were

some aspects which remained basically unchanged (Sidebotham 1996). At the beginning of the period, the Mediterranean basin contained a number of

independent or semi-independent political states in commercial-diplomatic contact and conflict with one another and with Rome. The larger states,

Seleucid Syria (until 64 BC), Ptolemaic Egypt (until 30 BC), Hasmonean and later Herodian Judea (until the 1st century AD), Nabatean Arabia (until

AD 106), states in Asia Minor like Galatia (until 25 BC), Cappadocia (until AD 18), and Commagene (until the 1st century AD) and other smaller

eastern powers, nominally independent client states of Rome and autonomous entities, as well as the few independent states in the West (the

kingdom of Mauretania until the 1st century AD), interacted as commercially independent, if not completely politically autonomous states.

Falling transport and communications costs in this era allowed seaborne trade of staples such as food, metals and stone in unprecedented

quantities (Morris, Saller & Scheidel 2007:10).

By the 4th century AD, the entire Mediterranean basin had been unified politically under the aegis of Rome.

Political unification also brought with it a unified system of coinage and laws regulating the commerce, although not a completely unified

economy. This 4th century economy was less laissez-faire than that of the 1st and 2nd centuries. The state and the church

took an increased interest and role in commerce, often at the expense of the independent entrepreneur. This transformation took place gradually

from the 1st century BC until the 4th century AD, the by-product of a series of patchwork-stopgap solutions to economic problems rather than a

deliberate long-term policy initiated by the Roman central government.

The Greek and Roman states were strong enough to protect property rights, but too weak to predate on their subjects so viciously that they smothered

economic activity (Morris, Saller & Scheidel 2007:11). The structures of citizenship were both positive and negative factors. On the positive side,

it is clear that ’free male citizens controlled their own fates to a degree that few ancient societies matched’ (Morris, Saller &

Scheidel 2007:11). On the negative side:

The ideology of egalitarian male citizenship drove many forms of economic activity to the margins of respectable society, sometimes creating a

demi-monde dominated by aliens, women and slaves; the high cost of citizen labour created strong demand for chattel slaves in some periods and places.

(Morris, Saller & Scheidel 2007:10)

Utilising information from the New Testament, Hock (1985) offers a helpful description of economics in New Testament times.10

He uses the terms ‘city,’ ‘countryside’ and ‘wilderness’ as general analytic categories for

classifying and organising the New Testament data into a coherent description of the ancient economy. These three terms are taken

from Mark 1:4–5, where the author of this Gospel describes John as preaching ‘in the wilderness’ and as drawing

people to him ‘from the whole Judean countryside and the city of Jerusalem’.

Sidebotham’s description of the commerce in the Roman Empire (1996) is very helpful.11

Although the rising volume of trade allowed some exploitation of comparative economic advantages around the Mediterranean, accomplished

largely through private enterprise and markets, Morris, Saller and Scheidel (2007) warn that:

States remained major economic actors; markets were fragmented and shallow, with high transaction costs; investment opportunities were limited;

money and markets generated intense ideological conflicts; and the economy remained miniscule by modern standards.

(Morris, Saller & Scheidel 2007:10)

Against this background of the general tendencies of the economics of the 1st century Graeco-Roman world, in what follows I narrow the focus down

to the era when and area where the addressees of 1 Peter lived.12

The structure of economics in the area where the addressees of 1 Peter lived

The geography of the areas identified in the address of 1 Peter

Four areas are designated in the address in 1 Peter 1:1: Πόντου,

Γαλατίας,

Καππαδοκίας,

᾽Ασίας καὶ Βιθυνίας

[Pntus, Galatia, Cappadocia, Asia end Bithynia]13 This is part of what is referred to as ’The

Eastern Mediterranean’, which around AD 106 included Achaea and Macedonia in modern Greece and the Republic

of Macedonia (former Yugoslavia), various divisions within the nation state of Turkey (Asia, Bithynia and Pontus,

Galatia, Cappadocia, Lycia and Pamphilia, Cilicia), as well as Syria, Judaea (later Palestine) and Arabia in the

Levant (Alcock 2007:674). Greek was the common language of the region’s elite, but numerous local languages

survived under the empire.

The area had a variety of micro-climates, with direct implications for agricultural success and the concomitant need for exchange.

This contributed to the fact that economic opportunities and options varied substantially, depending where in the region one operated

(Alcock 2007:674–5). Coastal or near-coastal communities had access to water transport, with harbour complexes, for example the

one at Ephesus, whilst the high tablelands of Anatolia remained relatively landlocked.

The demography of the areas identified in the address of 1 Peter

Long before the Greeks brought the plains and southern and western coastal regions of Asia Minor under their control, tribes of Hittite origin

lived in the valleys and dales of the Taurus Mountains (Breytenbach 1998:358). Since 133 BC, these areas slowly came under Roman rule. The Roman

government, however, had little interest in distant areas. Therefore they gave areas such as the northern cliffs of the Taurus Mountains, where

the Isaurians and the Hammonadians lived, to local small kings of Asia Minor, such as King Amyntas of Galatia. By subjecting the local population,

he could occupy the region with the approval of Rome and thus maintain stability there. This province was an administrative unit which encompassed

in the north the region of Galatia and in the south the areas of Pisidia, Lycaonia and Isauria (Breytenbach 1998:358).

The Augustan takeover appears to have inaugurated and extended an epoch of peace, taking disruptions of a more local character for granted. Only

in the 3rd century was the pax Romana significantly universally disrupted. There was, however, a price to be paid: taxation (in kind and

in cash) became a regular and more or less universal element in the economic configuration of the region (Alcock 2007:675–676).

Two essential parameters govern and are governed by the workings of the economy: the number of people in a region and their distribution in space

(Alcock 2007:676). The four areas mentioned in 1 Peter 1:1 cover about a quarter of a million square kilometres. Estimates of the number of inhabitants

during the last quarter of the 1st century range from four to eight million. The topography of the area varies much and it had different nations with

diverse cultures, languages, faiths and political histories (Elliott 1981:60–61). There were little urbanisation and military colonisation

(Broughton 1938:734). There is evidence that cities in parts of Cappadocia never had more than a 3rd of the surrounding area under their administration

(Broughton 1938:738). One of the consequences was that most of the people lived in small independent towns and villages. It furthermore seems as if

the borders of urbanisation were the borders of hellenisation as well.

Alcock (2007:677) shows that at least Ephesus could potentially have approached 100 000 inhabitants; most city units, however, comprised populations in the range

of 10 000–15 000, with an additional proportion of people dwelling outside the urban centre. Mitchell (1993:243–244) concurs,

arguing that relatively few of the estimated 130 cities in the various Anatolian provinces would have had more than 25 000 inhabitants.

Seemingly, there were no group loyalties surpassing local and regional differences (Elliott 1981:62), although at least religions, and Roman citizenship

could have been such unifying factors.

The main source for information about Jewish communities in the Roman provinces in Asia Minor is epigraphic and archaeological material

(Breytenbach 1998:332).14 Sch¸rer (1973:17–38), as well as Stern (1974:153), gives evidence from inscriptions and other documents

that there were Diaspora in all the areas mentioned in 1 Peter 1:1.15

There is not enough data to allow full clarity on the number of Jews in these areas,16 but estimations range from a quarter of a

million Jews out of a total population of 4 million (Reicke 1964:302–313), to one million Jews from a total population of eight million

(Broughton 1938:815). A reason for the growth in numbers was that during the 1st century AD, proselytism experienced a boom (Stern 1974:117).

There is also evidence that during the 1st century there was much stability in the economies of the Diaspora-Jews in these areas (Applebaum 1976:702).

These Jews, although fully participating in the Hellenistic culture and society, still viewed themselves as Jews, in spite of living abroad

(Safrai 1974:185). Frequent visits to Jerusalem, also by proselytes (Safrai 1974:199–205) witness to the fact that Judea was viewed as home.

It is therefore quite possible that, also in these areas, Christianity moved into the world via the bridge of Hellenised Diaspora Judaism (Breytenbach 1998:330).

The performance of economics in the area where the addressees of 1 Peter lived

In this section I theorise about the typical concerns of economists (like how much is produced, the distribution of costs and

benefits, or the stability of production in the relevant societies), focusing on production, distribution and consumption. The

work done by Alcock (2007) has been most helpful in this endeavour.

Production

Alcock (2007:678–682) paints a clear picture. The mosaic of landownership was exceedingly complicated. There was trend towards

increasing stratification in the control of agricultural wealth and the external interventions worked in favour of expansive, often

imperially privileged, landowners. The minor landowners, whose small-scale production continued to be important in the Roman Empire,

were still operative. Tenancy, together with the periodic hiring of free labour, was a very common means of organising production. In

the early imperial period there was an increase in agricultural activity and intensity of production. In some areas this was linked to

the market offered by a nearby conurbation, for others it might have been as a result of the stimulus of local natural resources (such

as timber, ore, or marble), their exploitation and the need to feed specialist workers. ‘There must have been successful surplus

production of basic necessities to feed, clothe and otherwise supply and support those units’ (Alcock 2007:682).

Alcock (2007:682–686) gives a survey of non-agrarian production, including ceramics, textiles and mining and quarrying.

Distribution

Alcock (2007:686–692) considers the distribution of goods in space, at the local, regional and long distance scale. ‘Local exchange’

covers the ambit of a particular city or large village, or a close nexus of these entities. ‘Regional distribution’ is the movement of goods

across distances exceeding travelling times between neighbouring cities, yet remaining in the ambit of the eastern provinces. There is clear evidence of

an increasingly vibrant network of regional interaction. ‘Long distance’ trade refers to the distribution of raw materials or finished

products either to Italy and the west, or their conveyance to (or through) the east from beyond the bounds of the empire. The agents involved in these

interactions were the Roman state, shippers [naukleroi] and merchants [emporoi], together with negotiatores of western origin

(Alcock 2007:691).

Consumption

The 3rd axis, consumption, drives the dynamics of both production and distribution. Alcock (2007:692–694) gives a summary of this axis,

the most difficult of the triad. There is a basic division between public and private and also huge gulfs of difference between super-cities and

villages, between the urban aristocracy and the rural poor. Local and regional efforts largely provided what civic populations needed to live.

There is great variety in civic access to and use of, goods, as well as in the factors underlying such variation. Up and down the social scale

the acquisition and utilisation of goods extended beyond the immediate local sphere. The denunciation in Revelation 18:12–14, revelling in

the destruction of a great city and its material abundance, provides a list of goods that would have been typical:

12 cargo of gold, silver, jewels and pearls, fine linen, purple, silk and scarlet, all kinds of scented wood, all articles of ivory,

all articles of costly wood, bronze, iron and marble, 13 cinnamon, spice, incense, myrrh, frankincense, wine, olive oil, choice flour

and wheat, cattle and sheep, horses and chariots, slaves—and human lives. 14 ‘The fruit for which your soul longed has

gone from you and all your dainties and your splendour are lost to you, never to be found again!’ (Rv 18:12–14)

To conclude this section then, the plurality of the ancient economy in the Roman east is clear. Alcock (2007:695) suggests a spatial perspective

on the organisation of economic process, be it for local patterns, regional cadences, or inter-regional flows, as one way to follow out alternative

sets of behaviour, whilst still allowing for their mutual influence.

On the issue of growth, Alcock sees many indicators to point in the following direction:

The development of urban hierarchy, the increase (however modest) in overall population, the expansion of rural settlement, the density of merchant

networks, the material evidence for more exchange and more consumption of more types of goods.17 (Alcock 2007:696)

|

The Economic–Historic Context of 1 Peter Constructed from 1 Peter

|

|

To construct the economic–historic context of the addressees of 1 Peter from the text, the relevant utterances need to be

identified and categorised. This can be done in different ways. In my own identification and categorisation, care has been taken

to use concepts and categories suggested by the text, as well as by the construction of the economic context of the addressees

from external sources and not to superimpose concepts and categories on the text of 1 Peter.18 The same care has been

taken to be emic in approach, optimally utilising the economic theory relevant to the 1st century AD and the probable economic

circumstances of the addressees.

The relevant portions of 1 Peter can be categorised into four main sections:

• the πάροικοι καὶ παρεπιδήμοι

[resident and visiting foreigners] label that the author gives the addressees

• teachings and exhortations concerned with economic matters

• mention of the precious metals silver and gold

• the metaphoric use of economic concepts and terminology.

The contribution each of these utterances makes towards constructing the economic–historic context of the addressees of 1 Peter is now investigated.

The πάροικοι καὶ παρεπιδήμοι

[resident and visiting foreigners] label of the addressees

Labelling the addressees19 as παρεπιδήμοις

διασπορᾶς ([visiting foreigners of the Diaspora], 1:1; 2:11) and

πάροικοι] ([resident foreigners], 2:11) and referring to their sojourn as the time of their

παροικίας [dwelling as resident foreigners] (1:17) do not imply a mere metaphoric,

figurative state of Christians being strangers in the world because they are citizens of heaven.20 Rather, the addressees were, already

before their conversion to the Christian faith, ’visiting and resident foreigners’ in the literal socio-political sense of the words.21

There is, however, apart from being foreigners in the literal socio-political sense of the word, a second level on which they (or at least some of them)

are παρεπιδήμοι [visiting foreigners]

(διασπορᾶς [of the Dispersion]) and

πάροικοι [resident foreigners]. This is the fact that they could have

been, before their conversion, proselytes and God fearers22 (the φοβούμενοι

[fearers] and the σεβόμενοι τόν θεόν

[those honouring God] as has been argued by Van Unnik (1980a:72–74).23 Labelling the addressees as

πάροικοι καὶ παρεπιδήμοι

[resident and visiting foreigners] (διασπορᾶς [of the Dispersion])

therefore does not merely describe their social position, it could indicate their previous status as ‘God-fearers’ as well.

The author of 1 Peter links on to this sense of πάροικοι καὶ

παρεπιδήμοι [resident and visiting foreigners]

(διασπορᾶς [of the Dispersion]), transforming the (in some ways) abusive title

to a proud self-identification by giving it a deeper and specific theologically positive sense. In a way it is part of the adoption of

the honorific titles of the Old Testament people of God and in another way it has been transformed into a proud self-identification in its

own right (Feldmeier 1992:104).24

Van Unnik (1980b:113) has already acknowledged that the historical data on the identity and circumstances of the addressees is not as extensive

as we could wish, or sufficient to allow us an exact definition of the situation. The data from the epistle, however, is sufficient to allow a

valid construction of the situation.25

The letter does not give any explicit cause for the πάροικοι καὶ

παρεπιδήμοι [resident and visiting foreigners] status of the addressees.

It is improbable that official persecution was the cause.26 The backdrop rather seems to be the socio-political status of

the Christian groups in the Diaspora, their daily relationships with Jews and other non-Christians and the difficulties that they, as

’resident and visiting foreigners’27 had to face daily. Their suffering, therefore, was most probably not caused

by official persecution, but by spontaneous local social ostracism28 (Balch 1981:95;29 Elliott 1976:252;

Elliott 1986:14;30 Van Unnik 1980a:79–80;31 Van

Unnik 1980b:113,116; see also Moule 1956–1957:1–1132).

p>

The hardships were, by and large, experienced within the smaller circle of the household.33 The

κύριος [owner] had more or less full authority over his wife or wives, children, servants and slaves

(see 1 Pt 3:1). When the κύριος did not convert to the Christian faith when any member of the household

did, it could result in severe discrimination against those who converted, with negative economic consequences. The

κύριος had the power to excommunicate any such member, leaving that person without the

protection and economic security of the household.

The mere fact that they were πάροικοι καὶ

παρεπιδήμοι [resident and visiting foreigners] would have

impacted negatively on their economic situation. Many of the πάροικοι

[resident foreigners] lived outside the cities, working as labourers on the farms of the landowners living in the cities

(Rostovtzeff 1957:255–257; Dickey 1928:406; Broughton 1938:628–648).

Teachings and exhortations on economic matters

Direct teachings and exhortations on economic matters are scarce, which could be an indication that economic matters were not really part of the

overt agenda in writing the letter. Only three exhortations touch on economic matters: pertaining to labour (the relationship of the

οἰκέται [household servants] with their

δεσπόται [employers], 2:18–25), the attitude towards greed and earthly goods

(nobody must be a thief, 4:15) and directives to women for the braiding of hair and wearing gold ornaments or fine clothing, 3:3).

Labour

The pericope 1 Peter 2:18–25 contains explicit exhortations to the οἰκέται

[household servants] for their relationship with their δεσπόται [employers].

The mere fact that only the οἰκέται are addressed could be an indication that not many

δεσπόται counted amongst the addressees. This in itself could signify that many of

the addressees shared the economic realities which faced οἰκέται.

Attitude towards greed and earthly goods

The author applauds willingness to suffer for what is good. Suffering because of theft, however, is not commended:

μὴ γάρ τις ὑμῶν πασχέτω

ὡς … κλέπτης ([‘But let none of you suffer as …

a thief’], 4:15). Theft need not necessarily point to the thief being poor. However, it may be motivated by an

urge to survive in a situation of severe poverty.

From the exhortation to wives in 1 Peter 3:3–4 not to adorn themselves outwardly by braiding their hair and by wearing gold

ornaments or fine clothing (ἔστω οὐχ ὁ ἔξωθεν

ἐμπλοκῆς τριχῶν καὶ

περιθέσεως χρυσίων ἢ

ἐνδύσεως ἱματίων κόσμος

[‘there should not be outward adornment: arranging of hair and wearing of gold or putting on clothes’]), it becomes clear

that (at least some of) the addressees had the means to braid their hair and wear jewels and fine clothes. This would indicate households

where more than the bare necessities could be afforded and that the women had access to the luxuries mentioned.

Silver and gold

Precious metals are used twice (gold, 1:7; silver and gold, 1:18), acknowledging its preciousness, but arguing that a spiritual gain is worth much more.

In 1:7 the genuineness of faith is compared with the preciousness of gold: ’… so that the genuineness of your faith – being more

precious than gold [πολυτιμότερον

χρυσίου]

that, although perishable, is tested by fire – may be found to result in praise and glory and honour’. In 1:18 silver and gold are mentioned:

‘You know that you were ransomed from the futile ways inherited from your ancestors, not with perishable things like silver or gold

[ἀργυρίῳ ἢ χρυσίῳ], but with the precious blood of Christ’.

Not much can be deduced from the mere mentioning of these precious metals. The fact that the author knew he would be understood need not mean that

the addressees possessed silver and gold themselves. It is, however, an indication that silver and gold were at least well known in their society

and could therefore be used effectively in the comparisons.

Metaphoric use of economic concepts and terminology

Whilst the teachings and exhortations on economic matters in 1 Peter are scant and commodities such as silver and gold mentioned only once,

the metaphoric use of economic concepts and terminology abounds. These function in the imageries of financial or judicial language (ransom

[ἐλυτρώθητε], 1:18; heir-image

[εἰς κληρονομίαν, 1:4;

συγκληρονόμοις, 3:7;

κληρονομήσητε, 3:9]; debt

[ἀποδιδόντες, 3:9]) and slavery

([θεοῦ δοῦλοι], 2:16); (3) household

([τοῦ οἴκου τοῦ θεοῦ], 4:17;

οἰκονόμοι ποικίλης

χάριτος θεοῦ [house managers of the manifold grace of God], 4:10).

Financial or judicial language

Ransom: In 1:18–19 the author reminds the addressees that they were ransomed with the precious blood of Christ

(ἐλυτρώθητε [you were ransomed]) from the futile ways inherited

from their ancestors. Although money (or some form of payment) is present in this ransom-image, the image itself gives no

window on the economic context of the addressees of the letter, other than that they know the ransoming convention.

Heir or to inherit: The author of 1 Peter uses the heir-image three times, in 1:4

(εἰς κληρονομίαν [to an inheritance]), 3:7

(συγκληρονόμοις [co-heirs]) and 3:9

(κληρονομήσητε [you may inherit]).

In 1:4 the author indicates the end goal of God’s re-begetting of the addressees as ’an inheritance

[εἰς κληρονομίαν] that is imperishable,

undefiled and unfading, kept in heaven for you’. In 3:7 he uses the same imagery, but now reminding the husbands

that their wives are co-heirs with them of the gracious gift of life

[συγκληρονόμοις

χάριτος ζωῆς]. And just two versus later, in 3:9 the author

admonishes the addressees to repay evil and abuse with a blessing, so that they may inherit a blessing:

ἵνα εὐλογίαν

κληρονομήσητε.

The heir-imagery shows that salvation in 1 Peter represents a present reality and anticipates the complete fulfilment thereof

in the future. A person that is an heir has this status in the present (see Gl 4:7).34 The inheritance itself,

however, is future and heirs can have absolute certainty that they will receive this inheritance.35 However, the

imagery in itself does not really shed light on the economic context of the addressees. At least its use shows that the author

had reason to believe that the image would speak to the addressees.

Debt: When exhorting the addressees not to retaliate, the author uses a concept from commerce,

ἀποδίδωμι [repay]: ’Do not repay

[μὴ ἀποδιδόντες] evil for evil or abuse for abuse;

but, on the contrary, repay with a blessing’. This metaphoric use of repayment shows that the addressees were at any

rate familiar with the phenomenon of debt.

Slavery

The author labels the addressees as ’slaves of God’ in 2:16: ’As slaves of God

[ὡς θεοῦ δοῦλοι],

live as free people, yet do not use your freedom as a pretext for evil’. Nothing much can be

deduced from the fact that the author uses this image. At least it shows that the addressees were familiar with slavery.

Household

The author uses the concepts of ’household’ and ’household management’ to portray the relationship between the addressees

(including himself) and God. In 4:17 he argues that the judgment begins with the household of God

(ἀπὸ τοῦ οἴκου τοῦ θεοῦ

[from the household of God]), referring to all Christians. The referent of the ’household of God’ is the household that the

addressees probably know and are members of. The exhortation in 4:10, that the addressees should serve one another like good stewards

[ὡς καλοὶ οἰκονόμοι] of the manifold

grace of God, with whatever gift each of them has received, also clearly functions within the household image.

Households, both urban and in the countryside, were the principal locus of economic activity and power (Hock 1985). The great urban households were

large.36 They included not only the householder and his wife, or wives and children, but also slaves (as is evidenced by the household

codes both inside and outside of the New Testament). These households might also have contained other persons on occasion or even for extended

periods of time.37

The referent of household is very clear, but the fact that the author uses this imagery does not disclose what type of households the addressees

were members of, or even what their position and function in these households would have been. What is clear, however, is that the addressees knew

a household and how it functioned.

The economic–historic context of the addressees of 1 Peter

The construction of the economic–historic context of the addressees, taking into consideration ’the minimal data on which any

socioeconomic profile of the addressees of 1 Peter’ (Horrell 2009:202) can be constructed, could be done quite successfully:

They lived in the districts comprising all of Asia Minor from the Cappadocian Mountains and the Anatolian Highlands down to the Black Sea in

the north. The economy was essentially agricultural. The vast majority lived as farmers and herders in the countryside that surrounded a city

and worked on land that was usually owned by an urban aristocracy, who lived off its surplus. The two groups, the one producers of wealth, the

other consumers of it, were related socially through the institution of the household and surrounded geographically by economically marginal

hills, mountains, or deserts, all lumped together as ’wilderness’. There was some, perhaps considerable, commercialisation, but the

economy remained fundamentally tied to agriculture. There could also have been the activities of free artisans and shopkeepers in the city

(and rural villages) and of brigand gangs in the caves of the wilderness and along its trade routes.

The addressees of 1 Peter were visiting and resident foreigners, people who had formerly been pagans. Most of them had probably had an intermediate

state as ’God-fearers’, having joined the Synagogue. Their πάροικοι [resident foreigners]

status impacted negatively on their economic situation. It is possible that many of them shared the economic realities which faced

οἰκέται [household servants]. They may have been so poor that they were drawn to theft.

However, there are indications that (some of) the households could afford more than the bare necessities, evidenced by the fact that

women had access to luxuries like hair braiding, gold ornaments and fine clothing. Furthermore, silver and gold were well known amongst

the addressees and could therefore be used effectively in his comparisons.

The metaphoric use of economic concepts and terminology at least indicates that the author expected his addressees to understand the images

he used: finance and judicial language (ransom, heir and debt) and slavery and household imagery. This could hardly have been the case if the

addressees were abjectly poor.

When these foreigners became Christians, it had positive and negative social consequences. On the positive side, they became part of a Christian

group and were no longer isolated individuals or small groups. Those who had been God-fearers and could not become full proselytes were no longer

second class members of the new Christian group. The new Christians, however, also had to cope with negative consequences as a result of their new

alliance. The unjust suffering which they had to endure as foreigners became even more severe, given that now one more dimension have been added

to their ’otherness’, the fact that they aligned themselves with an obscure foreign sect.

This resulted in further and more intense ostracisation and discrimination, with the inevitable economic consequences. These circumstances forced

them to either retaliate the injustices they suffered or forsake their new commitment to the Christian faith.

The author uses the letter to persuade the addressees of their status before God as saved persons, of the loving care he has for them and of

Christ’s vicarious suffering and subsequent glory and supreme power. He exhorts them to have a ‘good’ lifestyle

(τὴν ἀναστροφὴν ὑμῶν …

ἔχοντες καλήν [you must have your lifestyle as a good one], 2:12)

and to persevere in doing good (ἐν ἀγαθοποιΐᾳ [in good-doing], 4:19),

even amidst and in spite of their own suffering. In this way they must live up to their status as persons of whom it is said:

ὁ θεὸς … ἀναγεννήσας ἡμᾶς

[God … has begotten us anew] (1:3).

This means that, whatever their economic status, they could cope, because they had an inheritance kept in heaven.

Summarising the method for the construction of the economic–historic context

This method first of all entails that the genre of the New Testament letter is discussed, especially the issues of the identity and locality of the

addressees, as well as the dating of the letter. This impacts on the spatial and temporal issues involved in constructing the economic–historic

context. Then, as the second phase, the argument of the letter is explained, because this becomes a guiding principal in the economic analysis of the

letter. The third phase is the construction of the economic–historic context of the addressees, utilising external sources. This enables the

researcher to establish the general economic context of the 1st century Graeco-Roman world and to narrow it down to the era and area relevant for

the addressees. Then, as the fourth phase, the research returns to the text of the letter. The construction of the third phase is refined, utilising

the text of the letter. In this fourth phase the economic relevant portions of the letter are identified, categorised and interpreted. The fifth and

final phase is to formulate the economic-historic context of the addressees by synthesising the results of the different phases.

In honour of Andries van Aarde, New Testament scholar, colleague and friend.

Achtemeier, P.J., 1996, 1 Peter. A commentary on First Peter, Fortress Press, Minneapolis.

Applebaum, S., 1974, ‘The organization of the Jewish Communities in the Diaspora’, in S. Safrai & M. Stern (eds.),

The Jewish People in the First Century: Historical geography, political history, social, cultural and religious life

and institutions, pp. 464−503, Van Gorcum, Assen.

Aune, D.E., 1987, The New Testament and its literary environment, Westminster Press, Philadelphia.

Alcock, S.E., 2007, ‘The Eastern Mediterranean’, in I. Morris, R. Saller & W. Scheidel (eds.), The

Cambridge Economic History of the Greco-Roman World, pp. 671−697, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

doi: 10.1017/CHOL9780521780537.026

Balch, D.L., 1981, Let wives be submissive: The domestic code in 1 Peter, Scholars Press, Chicago.

Bassler, J.M., 1991, God and Mammon: Asking for Money in the New Testament, Abingdon, Nashville.

Beare, F.W., 1970, The First Epistle of Peter, 3rd edn., Blackwell, Oxford.

Berger, A., 1953, ‘Peregrinus’, in Encyclopedic Dictionary of Roman Law, vol. 64, part 2, pp. 626−627, The American

Philosophical Society, Philadelphia.

Bietenhard, H., 1979a, ‘Ξένος’ [Alien], in C. Brown (ed.),

The New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology, vol. 1, pp. 686−690, Paternoster Press, Exeter.

Bietenhard, H., 1979b, ‘Παρεπίδημος’

[Visting foreigner], in C. Brown (ed.), The New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology, vol. 1, p. 690, Paternoster Press, Exeter.

Bietenhard, H., 1979c, ‘Πάροικος’ [Resident foreigner],

in C. Brown (ed.), The New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology, vol. 1, pp. 690−691, Paternoster Press, Exeter.

Breytenbach, J.C., 1998, ‘Facets if Diaspora Judaism’, in A.B. du Toit (ed.), Guide to the New Testament, Volume II: The

New Testament Milieu, pp. 327−374, NG Kerk Boekhandel, Pretoria.

Broughton, T.R.S., 1938, Roman Asia Minor, The Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore.

Brox, N., 1979, Der erste Petrusbrief, Benziger, Z¸rich.

Cartledge, P.A., 1996, ‘Economy, Greek’, in Oxford Classical Dictionary, 3rd edn., Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Dickey, S., 1928, ‘Some economic and social conditions of Asia Minor affecting the expansion of Christianity’, in F.C. Porter, B.J.

Bacon & S.J. Case (eds.), Studies in Early Christianity, pp. 393−416, The Century Co, New York.

Doty, W.G., 1973, Letters in primitive Christianity, Fortress Press, Philadelphia.

Elliott, J.H., 1976, ‘The rehabilitation of an exegetical step-child: 1 Peter in recent research’, Journal of Biblical

Literature 95(2), 243−254.

doi: 10.2307/3265239

Elliott, J.H., 1981, A Home for the Homeless: A sociological Exegesis of 1 Peter, its Situation and Strategy, Fortress Press, Philadelphia.

Elliott, J.H., 1986, ‘1 Peter, its situation and strategy: A discussion with David Balch’, in C.H. Talbert (ed.), Perspectives on

First Peter, pp. 61−78, Mercer University Press, Macon.

Feldmeier, R., 1992, Die Christen als Fremde: Die Metapher der Fremde in der antiken Welt, im Urchristentum und im 1, Mohr, T¸bingen.

Finley, M.I., 1970, ‘Aristotle and economic analysis’, Past & Present 70, 3–25.

doi: 10.1093/past/47.1.3

Frend, W.H.C., 1967, Martyrdom and persecution in the Early Church, Doubleday, Garden City.

Gnuse, R.K., 1985, You Shall Not Steal: Community and Property in the Biblical Tradition, Orbis, Mayknoll.

Goldstein, H., 1974, ‘Die politischen ParÎnesen in 1 Petr und Rom 13, Bibel und Leben 15, 88−104.

Goppelt, L., 1978, Der erste Peterbrief, 8. Aufl., Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Gˆttingen.

Grant, R.M., 1977, Early Christianity and Society: Seven Studies, Harper & Row, San Francisco.

Guthrie, D., 1970, New Testament Introduction, Intervarsity Press, London.

Hammer, P.L., 1996, ‘Inheritance (NT)’, in D.N. Freedman (ed.), The Anchor Bible Dictionary, vol. 3, pp. 415−416, Doubleday, New York,

Hanson, K.C. & Oakman, Douglas E., 2008, Palestine in the Time of Jesus: Social Structures and Social Conflicts, 2nd edn., Fortress, Minneapolis.

Hengel, M., 1974, Property and riches in the Early Church: Aspects of a social history of early Christianity, Fortress Press, Philadelphia.

Hock, R.F., 1985, ‘Economics in New Testament Times’, in P.J. Achtemeier (ed.), Harper’s Bible Dictionary, Harper &

Row, San Francisco. (Accessed using Libronix)

Horrell, D.G., 2009, ‘Aliens and Strangers? The Socio-economic Location of the Addressees of 1 Peter’, in B.W. Longenecker & K.D.

Liebengood (eds.), Engaging economics: New Testament scenarios and early Christian reception, pp. 176−202, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids.

Janse van Rensburg, F., 2006, ‘A code of conduct for children of God who suffer unjustly: Identity, Ethics and Ethos in 1 Peter’,

Beihefte zur Zeitschrift f¸r die neutestamentliche Wissenschaft und die Kunde der ‰lteren Kirche 141, 473−510.

Johnson, L.T., 1977, The Literary Function of Possessions in Luke-Acts, Scholars Press, Missoula.

Judge, E.A., 1960, The social pattern of the Christian groups in the first century: Some prolegomena to the study of the New Testament

ideas of social organization, Tyndale, London.

Lewis, N. & Reinhold, M. (eds.), 1966, Roman civilization: Sourcebook II: The Empire, Harper & Row, New York.

Lohse, E., 1954, ‘Par‰nese und Kerygma im 1. Petrusbrief’, Zeitschrift f¸r die Neutestamentliche Wissenschaft und die Kunde der

‰lteren Kirche 45, 68−89. doi:10.1515/zntw.1954.45.1.68

Longenecker, B.W. & Liebengood, K.D. (eds.), 2009, Engaging economics: New Testament scenarios and early Christian reception, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids.

Louw, J.P, & Nida, E.A., 1996, Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament: Based on Semantic Domains, electronic edn. of the 2nd edn.,

United Bible Societies, New York.

MacMullen, R., 1966, Enemies of the Roman Order: Treason, unrest and alienation in the Empire, Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

McCaughey, J.D., 1969, ‘Three “persecution documents” of the New Testament’, Australian Biblical Review 17, 27−40.

Magie, D., 1950, Roman rule in Asia Minor to the end of the third century after Christ; Volume 1: Text; Volume 2: Notes, Princeton University Press,

Princeton.

Meikle, S., 1995, Aristotle’s Economics, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Mitchell, S., 1993, Anatolia: Land, Men, and Gods in Asia Minor: The Celts and the Impact of Roman Rule I, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Morris, I., Saller, R. & Scheidel, W. (eds.), 2007, The Cambridge Economic History of the Greco-Roman World, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Moule, C.F.D., 1956−1957, ‘The nature and purpose of First Peter’, New Testament Studies 3, 1−11.

doi: 10.1017/S0028688500017409

Nussbaum, M.C., 1996, ‘Economic theory, Greek’, Oxford Classical Dictionary, 3rd edn., Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Oakes, P., 2009, ‘Methodological issues in using economic evidence in interpretation of Early Christian Texts’, in B.W. Longenecker & K.D.

Liebengood (eds.), Engaging economics: New Testament scenarios and early Christian reception, pp. 9−34, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids.

Oakman, D.E., 2008, Jesus and the Peasants, Cascade, Eugene.

Reicke, B., 1964, The Epistles of James, Peter and Jude, Doubleday, Garden City.

Richard, E., 1986, The functional Christology of First Peter, in C.H. Talbert (ed.), Perspectives on First Peter, pp. 121−139, Mercer

University Press, Macon.

Rostovtzeff, M., 1957, The social and economic history of the Roman Empire, 2nd edn., rev. P.M. Fraser, Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Safrai, S., 1974, ‘Relations between the Diaspora and the land of Israel’, in S. Safrai & M. Stern (eds.), The Jewish People

in the First Century: Historical geography, political history, social, cultural and religious life and institutions, pp. 184−215,

Van Gorcum, Assen.

Saller, R.P., 2007, ‘Household and gender’, in I. Morris, R. Saller & W. Scheidel (eds.), The Cambridge Economic History of the

Greco-Roman World, pp. 87−112, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

doi: 10.1017/CHOL9780521780537.005

Schaefer, H., 1949, ‘Paroikoi [Aliens]’, in Paulys Realencyclop‰die der classischen Altertumswissenschaft, neue Bearbeitung,

Sechsunddreissigster Halbband, letztes Drittel, Band 28, vol. 4, pp. 1695−1707, Metzlersche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Stuttgart.

Schmidt, K.L. & Schmidt, M.A., 1967, ‘Πάροικος

[Alien]’, in Theological Dictionary of the New Testament, vol. 5, pp. 841−853, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids.

Schnider, F. & Stenger, W., 1987, Studien zum neutestamentlichen Briefformular, New Testament Tools and Studies, Brill, Leiden.

Sch¸rer, E., 1973, The history of the Jewish People in the age of Jesus Christ (175 B.C.–A.D. 135), 3 vols., transl. & ed.

G.Vermes, F. Millar, & M. Black, T&T Clark, Edinburgh.

Schweiker, W., & Mathewes, C. (eds.), 2004, Having: Property and Possession in Religious and Social Life, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids.

Seland, T., 2005, Strangers in the light: Philonic perspectives on Christian identity in 1 Peter, Brill, Leiden.

Selwyn, E.G., 1952, The First Epistle of St. Peter, MacMillan, London.

Sidebotham, S.E., 1996, ‘Roman Empire’, in D.N. Freedman (ed.), The Anchor Bible Dictionary, vol. 6, p. 629, Doubleday, New York.

Sleeper, C.F., 1968, ‘Political responsibility according to 1 Peter’, Novum Testamentum 10, 270−286.

doi: 10.2307/1560001

Stegemannn, E. W. & Stegemann, W., 1999, The Jesus Movement: A Social History of its First Century, transl. O.C. Dean, Jr., Fortress,

Minneapolis.

Stern, M., 1974, ‘The Jewish Diaspora’, in S. Safrai & M. Stern (eds.), The Jewish People in the First Century: Historical

geography, political history, social, cultural and religious life and institutions, vol. 1, pp. 117−183, Van Gorcum, Assen.

ThurÈn, L., 1989, ‘ “Imperative participles” and the rhetorical strategy of 1 Peter’, PhD Thesis, Department

of Theology, University of Uppsala.

Van Unnik, W.C., 1942 [1980a], ‘The Redemption in 1 Peter i 18–19 and the Problem of the First Epistle of Peter’, in C.K.

Barrett (ed.), Sparsa collecta: The collected essays of W.C. van Unnik, part 2, pp. 3−82, Brill, Leiden.

Van Unnik, W.C., 1956 [1980b], Christianity according to 1 Peter, in C.K. Barrett (ed.), Sparsa collecta: The collected essays of W.C.

van Unnik, part 2, pp.111−120, Brill, Leiden.

Young, F.M., 1973, ‘Temple cult and law in early Christianity: a study in the relationship between Jews and Christians in the early centuries’,

New Testament Studies 19, 325−338.

doi: 10.1017/S002868850000816X

|