|

Article Information

|

Author:

Johannes L. van der Walt1

Affiliation:

1School of Education, North-West University, Potchefstroom campus, South Africa

Note:

Hannes van der Walt, who retired at the end of 2000 as Dean of the Faculty of Education at the former

Potchefstroom University, is a specialist researcher attached to the Faculty of Education Sciences of

the North-West University (Potchefstroom campus). He specialises in Philosophy of Education and Religious Education Studies.

Correspondence to:

Hannes van der Walt

Email:

hannesv290@gmail.com

Postal address:

18 The Vines, Luneville Road, Lorraine, Port Elizabeth 6070, South Africa

Dates:

Received: 27 July 2010

Accepted: 16 Dec. 2010

Published: 04 July 2011

How to cite this article:

Van der Walt, J.L., 2011, ‘Understanding the anatomy of religion as basis for religion in education’,

HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 67(3), Art. #924, 7 pages.

doi:10.4102/hts.v67i3.924

Copyright Notice:

© 2011. The Authors. Licensee: AOSIS OpenJournals. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License.

ISSN: 0259-9422 (print)

ISSN: 2072-8050 (online)

|

|

|

|

Understanding the anatomy of religion as basis for religion in education

|

|

In This Original Research...

|

Open Access

|

• Abstract

• Introduction

• Methodology

• Conceptual-theoretical framework

• The numen at the heart of religion as dynamic entity

• The numen at the heart of religion

• The dynamic nature of religion

• The ‘test’: The complex structure of religion and the current South African Policy on Religion and Education (2003)

• Conclusion

• References

• Footnotes

|

|

This article sprung from previous structural analyses of religion as onticity, but went somewhat further by placing more

emphasis on encounters with the numinous as the core of religion, as well as on the dynamic character of religion. In doing

so, this analysis methodologically transcended the limitations of a structuralist view of religion. The post-structuralist

approach that was followed, assigns greater prominence to the interpretive and constructivist activities of the actors involved

in religious experience. Application of this expanded view of religion to the South African Policy on Religion and Education

(2003) demonstrated that the Policy caused a break between the various facets of religion education and resultantly disrupted

the wholeness of religion education.

Religion in education (schools) has for a long time now been a controversial subject in South Africa and elsewhere (Van der Walt

2009a). In one of a series of recent developments regarding religion in South African schools, self-confessed agnostic scholar

George Claassens announced his intention to persecute public (state) schools that offered Christian education on the grounds that

in terms of the 2003 Policy on Religion and Education, confessional religion education had been officially prohibited in

such schools (De Villiers 2009:1). He found this practice also to be in contravention of the Constitution of the Republic of South

Africa (Act 108 of 1996). According to Du Preez (2009:388), Claassen later decided not to proceed with his plan as a result of

pressures exerted on him and his family by proponents of confessional religion education in public (i.e. state) schools.

Claassen is not alone in denouncing confessional religion education in public schools. Roux and her co-researchers (refer Roux 2003;

Ferguson & Roux 2004; Roux & Du Preez 2005:279ff.; Roux 2005, 2006) are also critical of the fact that many South African

schools persist with confessional religion education despite official policy. In their opinion, religious literacy programmes should

be offered in public schools instead of confessional religion education; the former will better equip learners to cope with the religious

diversity prevalent in South African schools as well as in the broader community. A Professor of Theology of the Reformed Churches in South

Africa, Kruger (2009), also joins forces with them in arguing for confessional religion education to be removed from public (state) schools.

He contends, amongst others, that confessional religion education, specifically Christian religion education, cannot be adequately presented

in the conditions currently prevalent in public schools. It should therefore rather be provided by the church, the parental home and private

(Christian) schools.

This conundrum of whether confessional religion education should be included in the formal curriculum of the public (state) school is understandably

not restricted to South Africa. Literature abounds with reports about parents and teachers involved in the battle on both sides. Some of the contending

parties have pursued their cause right up to the highest international courts and councils (see, for instance, Hagesaether & Sandsmark 2006; Weisse

2003; Leirvik 2004).

My aim is to approach the problem of religion in and/or education from a different viewpoint. I contend that the place and role of religion in

education cannot be properly determined unless one understands the anatomy of religion in its entirety. This thesis springs from the work of

Abdool, Potgieter, Van der Walt and Wolhuter (2007), who describe religion as a multi-faceted phenomenon and claim that each of its facets has

important pedagogical consequences for religion in and/or education. Although I concur with what they say (Abdool et al. 2007:545–547)

about the basic structure of religion, I think that their analysis of the anatomy of religion is deficient on at least two counts, namely their

failure to recognise the numinous as the core of religion and their structuralist approach to the analysis of religion.

Firstly, evidence will be presented to support the contention that our current view of the structure of religion should be improved by inclusion of

the numinous, as well as that religion has to be viewed from a post-structuralist (interpretive-constructivist) vantage point to do justice to its

dynamic nature. I shall then put the more detailed picture of religion that I proffer to the test by applying it to the South African Policy on

Religion and Education that has been in effect since 2003. I intend to demonstrate that the Policy, as it stands, cannot do justice to

religion education as a seamless whole.

I follow an interpretive-constructivist and critical heuristic, the object of which is to determine the nature of a specific

situation, in this case the religious diversity which has to be regulated in schools. This heuristic enables one to discover the meaning

a certain situation has for those participating in it, in this case in the religious diversity in schools (Feinberg & Soltis 1985:89;

McKay & Romm 1992:48ff.). Interpretive-constructivist researchers maintain that there are multiple constructed realities and rather

than trying to be totally objective, they apply their own professional judgements and perspectives when interpreting the data. They insist

that the meaning of particular forms of social life, in this case education and religion, should be interpreted and thus reconstructed, in

order to be understood. As a result, they place more emphasis on values and context than on hard and fast data (McMillan & Schumacher

2010:6). Application of this heuristic enables me to look at religion as such and how it should be regulated in (state, public) schools as

constructed and interpreted realities of human interaction in social context. I draw meaning from the analyses of the constructs education

and religion and of associated constructs. This provides me with insights of a hermeneutical, interpretive and qualitative nature and of the

various contexts in which they appear (Onwuegbuzie, Johnson & Collins 2009:122–123). The post-conflict type of critical analysis

(Jansen 2009:255 et seq.) that I combine with interpretive-constructivism, furthermore helps me understand the sources of discontent

about how religion is currently accommodated in education (schools) and ‘to demonstrate that such discontent can be eliminated by

removing the structural contradictions that underlie it’ (Babbie & Mouton 2004:36).

Although I understand the importance of scientific objectivity and disinterestedness, I approach the problem of the anatomy of religion

and its pedagogical ramifications as a Christian educationist. All the research methods mentioned previously are therefore somehow interpretively

and constructively imbedded in my belief and conviction system. In saying this, I align myself with De Muynck and Van der Walt’s (2006:41)

view that we can only interpret, construct and criticise that which we have at hand as already having been given to us in creation and which are

subject to the order-giving laws of God as the Law-giver. Our activities as knowing subjects are confined to the boundaries of rationality. Put

differently, our rationality is exercised within the boundaries of the lawful structure of reality that we experience as pre-given by God.

|

Conceptual-theoretical framework

|

|

The main thrust of Abdool et al.’s (2007) work regarding respect for and tolerance of other religions and their adherents

in pedagogical settings is that students (learners, pupils), irrespective of religious affiliation, should attend the same schools and

classes. Well-trained teachers (educators) should further guide them not only to understand the generic structure and significance of

religion as a phenomenon, but also inculcate in them a spirit of respect for and tolerance of all the religions represented in their

particular environs. They contend that if learners understood that all forms of religion had some or other form of spirituality at their

core, they would be able to connect with one another at a deep spiritual level and that respect and tolerance would follow from that. This

view of the structure of religion was retained in their subsequent publications (Van der Walt 2009a, 2009b; Van der Walt, Potgieter &

Wolhuter 2010).

In terms of Abdool et al.’s ‘onion’ metaphor, every form of religion, ranging from atheism through agnosticism and

Gnosticism to the mainstream religions, consists of several layers, from the superficial and most conspicuous (rites, rituals, cults, worshipping

practices) on the ‘surface’, to the least directly observable (i.e. the deepest, inner spiritual layer). Respect for and tolerance of

their own and other religions can and should be brought home to learners with respect to each of these layers (Abdool et al. 2007:545–548).

Although this analysis of religion goes some distance towards understanding the structure of religion, I would argue that another structural

element, the numinous, lie at the core of all forms of religion and not spirituality. Their ‘onion’ metaphor furthermore depicts

religion as a static entity, consisting of a number of layers that can be theoretically peeled off one after the other for closer analysis;

therefore, I also contend for the propriety of another metaphor, provisionally referred to as the ‘smoke’ metaphor, as a depiction

of the dynamic ‘structure’1 of religion. In terms of this metaphor, religion is not a static, concrete phenomenon

(‘thing’; static onticity) with a fixed structure, but rather something more like a constantly changing state of mind that expresses

itself in a variable set of beliefs2.

This re-envisioning of religion helps us to see religion not as a ‘thing’ or an entity, but rather as a dynamic process involving all

of its ‘components’. It embodies the notion of dynamic interaction between the different ‘layers’, ‘components’

or ‘elements’ of religion. Given that religion is a dynamic state of mind and series of experiences, including of the numinous, terms

such as ‘structure’, ‘blueprint’ or ‘anatomy’ seem inappropriate and should be relinquished in favour of more

dynamic terminology.

|

The numen at the heart of religion as dynamic entity

|

|

Working on the analysis of Abdool et al. (2007), Van der Walt, Potgieter and Wolhuter (2010:36–37) contend that all

forms of religion reveal the following basic structure:

• Religion has a directly observable outer ‘layer’, which is of a cultic or ritual nature (Greek leitourgia, Latin

officia, English service, duty, ministry).

• Closely associated with this first ‘layer’ is the second: that of a sense of awe and respect owed to the god or gods (Greek

eusebia, Latin reverentia, English reverence or worship).

• Religions tend to have a theological, dogmatic and confessional ‘layer’ (Greek dogma, derived from dokein, to seem good;

Latin confessus, derived from confiteri, to admit).

• Religions also have a philanthropic or caring ‘layer’ (Greek philanthropia, philadelphia; Latin humanitas,

caritas; English love of humanity, brotherly love, charity).

• Religions have a faith or ‘pistic’ ‘dimension’ (Greek pistis, Latin pietas, English faithfulness, loyalty).

• At a deep level, religions have a spiritual ‘dimension’ (Greek pneuma, Latin spiritus, English breath or spirit)3.

On Abdool et al.’s (2007) analysis of religion, understanding and tolerance amongst adherents of different religious groups, for

instance in pedagogical settings, should in essence rest on an understanding of religions at the spiritual level, that is, the level that they

assume to be the deepest or innermost ‘level’ of religion. As I have said, my analysis of religion reveals Abdool et al.’s

view of religion to be inadequate in two respects: the true core of religion and its dynamic character.

The numen at the heart of religion

Despite the controversial nature of his theology, including his views about the numinous, my investigations lead me to agree with Otto’s

remark that ‘there is no religion in which [the numen or numinous] does not live as the real innermost core … without it no religion

would be worthy of the name’ (Otto 1923:6). The second meaning of ‘numen’, provided by Sinclair (1999:1015), resonates with this

view, namely that it is a guiding principle, force or spirit. The word is derived from Latin, literally meaning a nod (indicating obedience to a

command) and figuratively denoting divine power. The numen denotes ‘presence’ and is a Latin term for the power of either a deity or

a spirit that is present in places and objects, as in the Roman religion.4 The notion of ‘nodding’, contained in the numen

concept, refers to a sense of inherent vitality and presiding and associations with notions of ‘command’ and ‘divine majesty’.

It is etymologically akin to a word used by Immanuel Kant, namely noumenon, a Greek word referring to an unknowable reality underlying all

things (Wikipedia 2009b). According to Otto (1923:6), the numen or numinous was referred to in Hebrew as qadosh, to which the Greek agios

and the Latin sanctus and more accurately later still, sacer, are the corresponding terms. In essence, numen refers to life-energy.

This is the core meaning that I focus on in this discussion of numen5.

Numen refers to a quite specific element or moment in religious experience that is not rational in the normal sense of the word (though not irrational

in the normal sense of the word). It is a non-rational, non-sensory experience or feeling whose primary and immediate object is outside the self. It

therefore remains inexpressible, an (Gr.) arreton; ineffable6, in the sense that it completely eludes comprehension in terms

of concepts, a concept of the ‘supernatural’ (Paley 2008:3). There is, according to Slater (2004:246), no means of sharing, affirming and

acknowledging numinous experiences. Paul’s encounter with the Lord on the road to Damascus comes to mind. According to Acts 9:7, the men travelling

with him stood there speechless; they heard the sound but did not see anyone. Chopra (2009:215) refers to this encounter as ‘spectacular’,

one that made of him ‘a fiery believer’ whose further life and work were an ‘explosion of spirit’. On this account, Paul’s

conversion was an encounter with the Numinous: ‘In a flash a sinner sees the light and recognizes God’.7 Augustine’s

descriptions of the conversions of a friend and of himself to the service of the Lord are also reminiscent of encounters with the Numen. In the case

of the former, Augustine relates:

Then suddenly, filled with an holy love, and a sober shame, in anger with himself he cast his eyes upon his friend, saying, ‘Tell me, I pray thee,

what would we attain by all these labours of ours? what aim we at? what serve we for? Can our hopes in court rise higher than to be the Emperor’s

favourites? and in this, what is there not brittle, and full of perils? and by how many perils arrive we at a greater peril? and when arrive we thither?

But a friend of God, if I wish it, I become now at once.’ So spake he. And in pain with the travail of a new life, he turned his

eyes again upon the book, and read on, and was changed inwardly, where Thou sawest, and his mind was stripped of the world, as soon appeared. For

as he read and rolled up and down the waves of his heart, he stormed at himself a while, then discerned, and determined on a better course; and

now being Thine, said to his friend, ‘Now have I broken loose from those our hopes, and am resolved to serve God; and this, from this hour,

in this place, I begin upon (emphasis added). (Augustine 1909–1914: Book 8, line 40)

His own encounter with the Lord was as follows:

Thou, O Lord, while he was speaking, didst turn me round towards myself, taking me from behind my back where I had placed me, unwilling

to observe myself; and setting me before my face, that I might see how foul I was, how crooked and defiled, bespotted and ulcerous. And

I beheld and stood aghast; and whither to flee from myself I found not. And if I sought to turn mine eye from off myself, he went on with

his relation, and Thou again didst set me over against myself, and thrustedst me before my eyes, that I might find out mine iniquity, and hate it.

(Augustine 1909–1914: Book 8, line 41)

Experience of the numinous, says Mathew (2005:388), is like ‘an experience out of the blue, from the other side of the rainbow’.

It is possible, according to her (2005:385–386), that an experience may open a window in the perimeter of a person’s experienced

mind with the potential for connection (or even reconnection) with the numinous, or, as Greene (2004:29, 31) refers to it, the ‘totally

other’ super-nature.

Space constrains me from expanding much on the averred characteristics of the numinous or on experience of the numinous. Encounters with the

numinous are only reserved for people; only a human being can feel connected with the numen or archč, which from then on forms the heart, core

or reference point for the person, whether in transcendent or immanent sense (see Calvin 1584. I, ch. 3, paragraph 1; Barge 2004:39; Slater

2004:246, 251; Wilhelm 2004:565; Matthew 2005:386–390; Crosby 2007:508; Schlamm 2007:404–405; Swer 2008:245; Aronson 2008:20; Jung

in Colman 2008:356, 362; Jarvis 2008:65). Connectedness with the numinous, in other words, religiosity-in-essence, forms part of a human being’s

search for meaning (Kruger, Lubbe & Steyn 1996:4–5). The numinous provides religious knowledge inaccessible to rational understanding. It

falls outside the limits of the canny, is contrasted with it and fills the mind with blank wonder (Schlamm 2007:405).

The dynamic nature of religion

According to Gibson (1984:6–12), a structuralist approach, in this case of religion (the seven ‘layers’ thereof: the six

distinguished by Abdool et al. plus the numen or numinous at the heart of religion), embodies the following six structuralist ideas:

• It emphasises the wholeness of religion, despite the fact that it is perceived to consist of several ‘layers’.

• Its reality does not lie in the different components or layers of religion, but in the relationships between them.

• The person who observes (analyses) religion becomes part of the religious system.

• The whole religious system maintains itself; it governs its parts such that they change, if required to do so, to ensure the preservation of the totality.

• One can only study and describe a structure, in this case, religion, at a given moment rather than its development over time.

• The laws of the entity (religion) are both structured and structuring, that is, they allow a dynamic between part and part, part and whole.

In that dynamic, change is a necessary consequence. This transformation is a key idea of structuralism.

A structuralist description of religion goes some way towards explaining the ‘anatomy’ of religion, but it places insufficient emphasis on its

dynamics. A post-structuralist perspective (McKay & Romm 1992:48) is helpful here in that it depicts religion as a structure, the meaning of which is

constantly (re-)constructed, (re-)constituted and sustained through the ongoing interpretive activities of the social actors (researchers like myself,

readers of this article, people who practise a particular religion, believers, etc.). This constructive process is, however, not an epistemology of

shaping knowledge out of nothing; knowledge is (re-)interpreted and (re-)constructed on the basis of a pre-given, law-governed reality or creation.

The emphasis in an interpretive-constructivist approach is on the activity of all the participants, in other words, the transformation of knowledge

(Lagerweij & Lagerweij-Voogt 2005:286, 327).

In terms of a post-structuralist or constructivist approach, the different components or elements of religion are viewed as dynamics of religion as an

onticity, that is, as an ontic being (literally: be-ing) that is constantly subject to dynamic change and adaptation, according to circumstance.

Religion in any particular form should therefore not be seen as a monolithic system of neatly arranged compartments, components and/or levels,

but rather as an abundance of experiences and awarenesses that confusingly ‘bleed’ into one another and resultantly, changes shape

continuously. To borrow a remark by Crosby (2007:508) from a slightly different context, it is a complex blending of unity and diversity, order

and disorder, continuity and novelty, persistence and change.

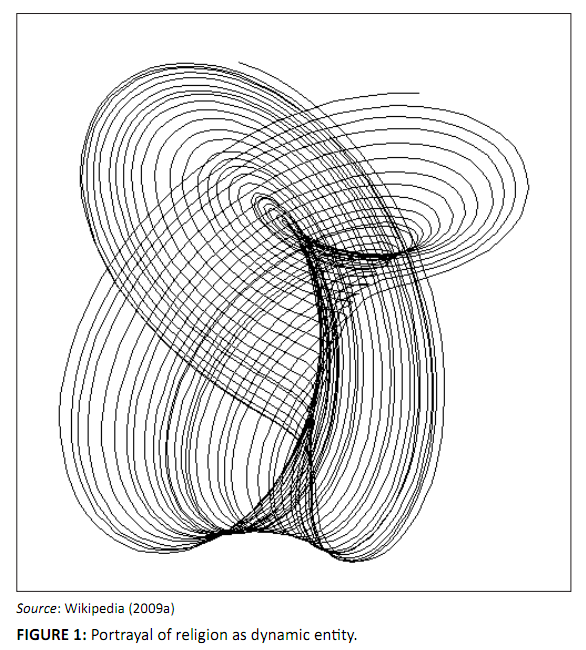

After casting around for an appropriate metaphor to portray religion as dynamic entity, I found the following graphic to fit the bill:

This graphic (see Figure 1) portrays religion as a swirling, twirling and whirling spiral, less like a solar system with a central body and certain

religious aspects orbiting around it, or a pyramid with the numinous, for instance, at the base and spirituality at the apex, or an onion, the layers

of which can be figuratively or theoretically peeled off. The spiral, like a column of smoke, turns and returns again and again to the same point as

it continues to grow in a particular direction. Like the particles in a column of smoke, the actual behaviour of the elements of religion appears

unpredictable and random, but as Davies (1992:30–31) argues, nothing in creation behaves unrestrictedly chaotic in a lawless universe. The relative

probabilities of the different possible states of the various elements of religion are determined within a law-governed cosmos. In doing what they do

in response to the circumstances and as a result of human actions and decisions, the various elements of religion serve a creative purpose, namely, to

provide form for something new (Young 2001:28). Although religion can be termed a ‘structure’, it is essentially a dynamic one, constantly

subject to change depending on the interpretive and constructive actions of the actors involved. The job of the religion scientist is to uncover

patterns in religion and to try to fit them in theoretical schemes. The question of why there are patterns (cosmic laws for religion) and why such

theoretical schemes are possible, lies more in the ambits of philosophy and theology than in the scope of religion science as such (also see Davies 1992:31).

|

FIGURE 1: Portrayal of religion as dynamic entity.

|

|

|

The ‘test’: The complex structure of religion and the current South African Policy on Religion and Education (2003)

|

|

The workability of the foregoing portrayal of religion as complex, multi-dimensional and above all, dynamic entity can be put to the test

by looking at the current South African Policy on Religion and Education (2003). Before I do this, I have to point out that in previous

publications I have been propounding two parallel arguments with regard to respect for and tolerance of religious diversity and differences in

educational settings. Some publications argue for confessional and structural pluralism, that is, a system in which provision is made for the

separate confessional religion education of students (learners, pupils) adhering to different religions, including in separate institutions

(schools). I regard this strategy as of import for very young children who have not yet acquired a good mastery of the religion preferred by

their parents. My parallel argument for accommodating learners adhering to different religions in one and the same class and school is arguably

more appropriate for older learners or in situations where confessional and institutional pluralism is deemed impracticable.

Very young children should receive confessional religion education in their parental homes and in their religious institutions such as churches,

mosques, temples and synagogues, for the simple reason that their tender minds will become confused if they were exposed to the tenets of several

religions during the first few years of formal schooling. This will be detrimental to their mastering of their own religion(s). Students from the

age of approximately 14 should be exposed to the various religions represented by the student population in their school in order for them not only

to understand those religions, but also to learn to respect and tolerate them.

I base this thesis on the following. Every learner as a human being is essentially homo religiosus, in other words, religion forms an

essential part of being human. Students have to encounter all the religions represented in their school in order to understand, know and respect

their own religion as well as those of others. The assumption in the South African Policy on Religion and Education (2003: articles 54 and 55)

that ‘(confessional) religious instruction (with a view to the inculcation or adherence to a particular faith or belief) is primarily the

responsibility of the home, the family, and the religious community’ and therefore ‘may not form part of the formal school programme’

cannot be supported. Religion is a whole, comprising various distinguishable elements; religion instruction (religious instruction, according to the

Policy) should resultantly also be a seamless undertaking for the religious wholeness of the students to be safeguarded.

The South African Policy on Religion and Education (2003) causes an artificial rupture between on the one hand religion education, that is,

instruction for the purpose of inculcating in young people the tenets of a particular faith and religious observances (article 58 ff.) and religion

education as a formal examinable school subject (article 17 ff.) on the other. Most of the stipulations in the Policy are devoted to the

latter as part of the formal school curriculum. What the Policy does is to destroy the unity of religion and hence that of religion education

as an entirety. It bans a core aspect of students’ religious experiences from the school to the parental home and the religious institution.

Although it provides for the accommodation of religion instruction in schools (outside of the formal curriculum and school times), it places religion

instruction in the hands of the parents and of clergy and not the students’ regular teachers. This not only disrupts the unity and wholeness of

religion and religion instruction, but also deprives the students from experiencing the richness of the religious diversity in their school.

The Policy also creates the danger of religious confrontation on the school grounds. Danger lurks when confessional religion is not fairly and

equitably taught and discussed under regulated circumstances, with the necessary pedagogical expertise and guidance. The lack of pedagogical guidance

in this respect in schools is detrimental to the creation of social capital in South Africa and therefore not in the interest of the common or public good.

Religion, composed of several elements or layers and assuming unpredictable shapes as a result of adherents’ interpretations, constructions and

meaning-giving, also embraces spirituality, defined by Nolan (2009:57) as ‘the kind of subjective attitudes and personal consciousness we need

in order to be at all times honest and fair, among other things’ (also refer Rawls 2007:566). Spirituality, according to Abdool et al.

(2007:547), embodies the human being’s quest for depth and values and describes how people relate their beliefs and actions towards god(s) or

God and/or otherness, to their own being and core values and express them in religious practices. Spirituality has to do with the inner life of the

individual (Nolan 2009:58). These definitions imply that students inadvertently and unwittingly bring their spirituality as part and parcel of their

entire religiosity to school with them and teachers should be afforded the time and opportunity to help them encounter the wealth of spiritual diversity

thus brought to school.

Nolan’s (2009:58–63) discussion of the role of spirituality pivots on two ideas. Firstly, spirituality is about the search for the truth

about oneself, one’s motives, obsessions, compulsions, desires, fears and self-centredness and about learning about love and compassion for others.

It is about learning about oneself as one is and how to deal with the truth about oneself. Spiritual understanding of the self, he avers, helps one deal

with one’s intellectual pride, swollen ego, emotional immaturity, childishness, prejudice and partiality, self-centredness, competitiveness and

individualism. Secondly, according to Nolan (2009:64), spirituality helps one transcend all of these aspects of self-centredness and to become what he

terms an organic person, in other words, a person who serves the interests of social justice. The organic person, in this case student, is committed:

… to any change that is for the benefit of all the people. Another way of describing this is to say that the [organic person, i.e. the student]

works for the common good, not for his or her own selfish interests nor for the interests of the ruling class. (Nolan 2009:64–65)

My view about the place of religion in schools resonates with Nolan’s about spirituality. The Abdool et al. (2007) analysis revealed the

importance of spirituality; together with experience of the numinous, it lies at the heart of being human and of being a religious being. To artificially

separate the religious (spiritual) experience and orientation of a learner into certain facets that are allowed in school and others that are not, is to

fail to understand the integral nature of religion and hence of spirituality and of being human. This, as we have seen, is not in the interest of promoting

social justice and the search for the common or public good.

What would we gain by amending the South African Policy on Religion and Education (2003) so that it would provide social space for all the

students’ religious experiences in the formal school programme? Firstly, we would still have Religion Education as a formal examinable school

subject, as stipulated by the Policy. Secondly, we would still have space for religious observances as currently provided for by the Policy.

Thirdly and most importantly, we would have provided social space for religion instruction (‘Religious Instruction’, according to the

Policy) during the formal school programme, under regulated circumstances and managed by teachers specially trained8 to present

and manage diversity programmes. Instead of banning religious differences from the formal school programme we would have deliberate encounters with

religious differences and diversity within the school programme, presented and managed by appropriately trained teachers.

In the social spaces specially designed for (confessional) religion instruction in schools, the students will be exposed to (inter alia) the

numinous experiences of their classmates (Barge 2004:39), to the rationale behind the various rituals of the different religions, their worship practices,

their dogmas, their ways of caring for others (essential for creating social capital, and for promoting social justice), their faith and belief structures

and their spirituality. Jarvis (2008:71) is correct in saying that ‘at this point different faiths can join together and this lies at the heart of

inter-faith dialogue’.

The current approach bans religious diversity from schools as a measure to pre-empt possible religious conflict. This not only promotes ignorance

about others and their religious tenets and peculiarities but also inspires suspicion about others and their faith. The alternative approach proposed

above will promote deeper understanding and tolerance of others and what they believe (Gray 2006:307) and will contribute to the common good, that is,

to the promotion of social justice and also to our store of social capital (Van der Walt 2009c:2–5). The promotion of Rawlsian justice as fairness

(Rawls 2007:565) is closely connected to the development of ethical standards (see Scott & Marshall 2009:381; Strauss 2009:515, 569; Nieuwenhuis

2010:15, and particularly Sankowski 2005:463).

This article commenced with the contention that religion has to be viewed from a post-structuralist interpretive-constructivist

point of view. I offered several sets of evidence in support of this contention. I firstly argued that the view put forward by Abdool

et al. (2007) and others about the structure of religion was incomplete in that it did not also embrace the notion of the numen

(numinous), which is at the heart of religion. I then demonstrated that a structuralist view of religion was inadequate for a proper

understanding of the dynamic nature of religion. A post-structuralist interpretive-constructivist view of religion enables us to construct

a more sophisticated picture of religion. Evaluation of the current South African Policy on Religion and Education (2003) revealed

that the Policy should be revisited to also provide for the teaching of confessional religion to older students for the purpose of

inculcating knowledge, insight and understanding of the religious diversity in schools (and in the surrounding communities). Such understanding

will lead to the more successful creation of social capital amongst South Africans and will contribute to greater social justice (fairness

for all) and hence to the common good.

Abdool, A., Potgieter, F.J, Van der Walt, J.L. & Wolhuter, C.C., 2007, ‘Inter-religious dialogue in schools: a pedagogical and

civic unavoidability’, HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 63(2), 543−560.

Aronson, R., 2008, Living without God, Counterpoint, Berkeley, CA.

Augustine, Saint, 1909–1914, The Confessions of St Augustine, Book 8, pp. 354−430, The Harvard Classics, Harvard.

Babbie, E. & Mouton, J., 2004, The practice of social research, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Barge, L., 2004, ‘Exploring the numinous in literature: Learning from Paul on Mars Hill’, Journal of Education and Christian

Belief 8(1), 35−52.

Calvin, J., 1584, Institution, transl. into the Afrikaans language by A. Duvenage & L.J. du Plessis, 1951, Die Institusie van

Calvyn, SACUM, Bloemfontein.

Chopra, D., 2009, The Third Jesus, Rider Books, London.

Colman, W., 2008, ‘On being, knowing and having a self’, Journal of Analytical Psychology 53, 351−366.

doi:10.1111/j.1468-5922.2008.00731.x

Crosby, D.A., 2007, ‘Further contributions to the dialogue’, Journal for the Study of Religion, Nature &

Culture 1(4), 508−509.

Davies, P., 1992, The Mind of God: Science and the search for ultimate meaning, Penguin, London.

De Muynck, B. & Van der Walt, J.L., 2006, The call to know the world, Buijten & Schipperheijn, Amsterdam.

De Muynck, B., 2008, Een Goddelijk beroep, Groen, Herenveen.

De Villiers, J., 2009, ‘Hare waai oor skolegodsdiens’, Rapport, 20 September, p. 1.

Du Preez, M., 2009, Dwars: Mymeringe van ‘n gebleikte Afrikaan, Zebra Press, Cape Town.

Feinberg, W. & Soltis, J.F., 1985, School and society, Teachers College Press, New York.

Ferguson, R. & Roux, C., 2004, ‘Teaching and learning about religions in schools: Responses from a participation action

research approach’, Journal for the Study of Religion 17(2), 5−23.

Gibson, R., 1984, Structuralism and Education, Hodder and Stoughton, London.

Gray, D., 2006, ‘Mandala of the self: embodiment, practice and identity construction in the Chakramsamvara tradition’,

The Journal of Religious History 30(3), 294−310.

Gray, J., 2003, Straw dogs, Granta Books, London.

doi:10.1111/j.1467-9809.2006.00495.x

Greene, J.T., 2004, ‘Covenant and Ecclesiology: Trusting human and God’, International Congregational Journal 4(1), 29−42.

Hagesaether, G. & Sandsmark, S., 2006, ‘Compulsory education in religion – the Norwegian case: an empirical evaluation of RE in

Norwegian schools, with a focus on human rights’, British Journal of Religious Education 28(3), 275−287.

doi:10.1080/01416200600811402

Hewson, D. & Carter, L., 2007, ‘Book review. The idea of the numinous. Contemporary Jungian and Psychoanalytic

perspectives’, Journal of Analytical Psychology 52, 237−243.

doi:10.1111/j.1468-5922.2007.00655_1.x

Jansen, J.D., 2009, Knowledge in the blood, Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA.

Jarvis, P., 2008, ‘Religious experience: Learning and meaning’, Transformation 25(2), 65−72.

Kruger, J.S., Lubbe, G.J.A. & Steyn, H.C., 1996, The human search for meaning, Via Afrika, Pretoria.

Kruger, P.P., 2009, ‘Godsdiens in openbare skole… ja en nee’, Die Kerkblad 112(3229), 10−12.

Lagerweij, N. & Lagerweij-Voogt, J., 2005, Anders kijken, Garant, Apeldoorn.

Leirvik, O., 2004, ‘Religious education, communal identity and national politics in the Muslim world’, British Journal of

Religious Education 26(3), 223−236.

doi:10.1080/0141620042000232283

Mathew, M., 2005, ‘Reverie: between thought and prayer’, Journal of Analytical Psychology 50, 383−393.

doi:10.1111/j.0021-8774.2005.00539.x

McKay, V. & Romm, N., 1992, People’s Education in Theoretical Perspective, Maskew Miller-Longman, Pinelands.

McMillan, J.H. & Schumacher, S., 2010, Research in education. Evidence-based inquiry, 7th edn., Pearson, Boston, MA.

Nieuwenhuis, J., 2010, ‘Social justice in education revisited’, paper presented at Örebro-Unisa International Conference, UNISA

Muckleneuk Campus, Pretoria, 01−03 February.

Nolan, A., 2009, ‘The spiritual life of the intellectual’, in W. Gumede & L. Dikeni (eds.), The poverty of ideas: South African

democracy and the retreat of intellectuals, pp. 56−66, Jacana Media, Sunnyside.

Onwuegbuzie, A.J., Johnson, R.B. & Collins, K.M.T., 2009, ‘Call for mixed analysis: a philosophical framework for combining qualitative and

quantitative approaches’, International Journal of Multiple Research Approaches 3, 114−199.

Otto, R., 1923, The idea of the holy, viewed 14 December 2009, from

http://books.google.co.za/books?id=0-9yrD6HOxUC&dq=rudolf+otto&printsec

Paley, J., 2008, ‘Spirituality and Nursing: a reductionist approach’, Nursing Philosophy 9, 3−18.

doi:10.1111/j.1466-769X.2007.00330.x

Pickthall, M.M., 1994, Introduction to The Holy Q’uran, Millat Book Centre, Delhi.

Rawls, J., 2007, ‘A theory of justice’, in H. LaFolette (ed.), Ethics in practice, pp. 565−590, Blackwell, Malden, MA.

Republic of South Africa, 2003, ‘National Policy on Religion and Education. National Education Policy Act, 1996 (Act no. 27 of 1996)’,

Government Gazette, 459(25459), Government Printers, Pretoria.

RSA (see Republic of South Africa).

Roux, C., 2003, ‘Playing games with religion in education’, South African Journal of Education 23(2), 130−134.

Roux, C., 2005, ‘Religion in education: perceptions and practices’, Scriptura 89(2), 293−306.

Roux, C., 2006, ‘Innovative facilitation strategies for religion education’, in M. de Souza, K. Engebretson, G. Durka, R. Jackson &

A. McGrady (eds.), International Handbook of the Religious, Moral and Spiritual Dimensions in Education, part 2, pp. 1293−1306,

Springer, Dordrecht. doi:10.1007/1-4020-5246-4_91

Roux, C. & Du Preez, P., 2006, ‘Religion in education: an emotive research domain’, Scriptura 89(2), 273−282.

Sankowski, E.T., 2005, ‘Justice’, in T. Honderich (ed.), The Oxford Companion to Philosophy, pp. 463−464, University Press, Oxford.

Sayers, D.L., 2009, ‘The Lost Tools of Learning’, Redeemer Classical School, viewed 10 December 2009, from

info@redeemerclassical.org/http://www.redeemerclassical.org

Schlamm, L., 2007, ‘C G Jung and the numinous experience: Between the known and the unknown’, European Journal of Psychotherapy

and Counselling 9(4), 403−414.

doi:10.1080/13642530701725981

Scott, J. & Marshall, G., 2009, Oxford Dictionary of Sociology, University Press, Oxford.

Sinclair, J.M., (ed.), 1999, Collins Concise Dictionary, HarperCollins, Glasgow.

Slater, T.S., 2004, ‘Encountering God: personal reflections on geographer as pilgrim’, Area 36(3), 245−253.

doi:10.1111/j.0004-0894.2004.00221.x

Strauss, D.F.M., 2009, Philosophy: The discipline of the disciplines, Paideia Press, Grand Rapids, MI.

Swer, G.M., 2008, ‘Nature, Physis and the Holy’, Journal for the Study of Religion, Nature and Culture 2(2), 237−257.

Van der Walt, J.L., 2009a, ‘So waai die hare oor skolegodsdiens!’, Word and Action 49(410), 14−18.

doi:10.1080/09637490903500507

Van der Walt, J.L., 2009b, ‘Spirituality: the new religion of our time?’, In die Skriflig 43(2), 251−269.

Van der Walt, J.L., 2009c, ‘Metaphorical bridge-building for promoting understanding and peaceful coexistence’, HTS Teologiese

Studies/Theological Studies 65(1), 280−284.

Van der Walt, J.L., Potgieter, F.J. & Wolhuter, C.C., 2010, ‘The Road to Religious Tolerance in Education in South Africa (and Elsewhere):

A Possible ‘Martian Perspective’, Religion, State and Society 38(1), 29−52.

Weisse, W., 2003, ‘Difference without discrimination: religious education as a learning field for social understanding?’, in R.

Jackson (ed.), International perspectives on citizenship, education and religious diversity, pp. 191−208, RoutledgeFalmer, London.

Wikipedia, 2009a, ‘Mandalas’, viewed 10 December 2009, from

http://images.google.co.za/images?sourceid=navclient&rlz=1T4SKPB_enZA282ZA283&q=mandalas&um=1&ie=UTF-8&ei=8DQhS-rQAeOZjAe7tIzbBw&sa=X&oi=image_result_group&ct=title&resnum=1&ved=0CBgQsAQwAA

Wikipedia, 2009b, ‘Numen’, viewed 10 December 2009, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Numen

Wilhelm, V., 2004, ‘Body, Numinous, words’, The Southern Review 40(3), 555−567.

Young, A.J., 2001, ‘Mandalas. Circling the square in education’, Encounter: Education for Meaning and Social Justice 14(3), 25−33.

|

|