|

Article Information

|

Author:

Jonathan A. Draper1

Affiliation:

1School of Religion and Theology, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

Correspondence to:

Jonathan Draper

Email:

Jonathan Draper

Postal address:

School of Religion and Theology, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Private Bag X101, Scottsville, Pietermaritzburg 3209,

South Africa

Dates:

Received: 19 July 2010

Accepted: 09 Aug. 2010

Published: 07 June 2011

How to cite this article:

Draper, J., 2011, ‘The moral economy of the Didache’, HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 67(1), Art. #907, 10 pages.

doi:10.4102/hts.v67i1.907

Copyright Notice:

© 2011. The Authors. Licensee: OpenJournals Publishing. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License.

ISSN: 0259-9422 (print)

ISSN: 2072-8050 (online)

|

|

|

|

The moral economy of the Didache

|

|

In This Original Research...

|

Open Access

|

• Abstract

• Introduction

• Aaron Milavec: The economic safety net

• The moral economy of the Didache

• God as Patron

• Community members

• Housetables

• The food market

• Outsiders

• Conclusion

• References

• Footnotes

|

|

This article applies the model of the moral economy in the ancient world, as formulated by Karl Polanyi and applied by Halvor Moxnes, to the

economic relations reflected in the Didache. The study partly confirms Aaron Milavec’s contention that the instructions in the

text would provide an ‘economic safety net’ for members of the community by putting in place a system of generalised reciprocity

and redistribution, although Milavec’s depiction of the community as an ‘urban working class’ movement is found to be

anachronistic. The ‘communion of the saints’ is very much an economic system with aspects of resistance to the Roman imperial

system. However, the moral economy of the Didache is seen to reflect a number of ambiguities, particularly in its adoption of the

Christian Housetable ethic but also in its adoption of the patron client terminology in the dispute between prophets and teachers on the one

side and bishops and deacons on the other.

In his recent book, Jesus in Context: Power, People, and Performance (2008), Richard Horsley builds on many years of work on the

‘Q’ community to propose that this hypothetical text reflects the ‘moral economy’ of the peasant villages of Galilee.

In this, he argues, it reflects the quintessential shape of the Jesus movement as a movement of social renewal in a period of social and economic

crisis brought about by Roman imperial rule. He bases his hypothesis largely on the work of James C. Scott (1976, 1985, 1990), which explores the

dynamics of peasant society and the conditions leading up to peasant revolts in many cultures. What excites Horsley’s interest, in particular,

is Scott’s insistence that social-religious movements amongst the peasants are key to the defence and mobilisation of this moral economy:

This symbolic refuge is not simply a source of solace, an escape. It represents an alternative moral universe in embryo—a dissident sub-

culture, which helps unite its members as a human community. (Scott 1976:238, 240 cited by Horsley 2008:214)

Here, Horsley finds the key to the nature of Jesus’ covenant renewal movement in the peasant villages of Galilee as expressed in ‘Q’,

an analysis I find convincing in its broad outlines (Draper 1995; Horsley & Draper 1999; Draper 2006).

In pushing this perspective forward, I would like to pay tribute to Professor Andries van Aarde for his pioneering work in introducing many South African

scholars to the use of social scientific tools in the study of New Testament texts, particularly in research into the historical Jesus. Professor van Aarde

has also emphasised the importance of extra-canonical texts in understanding the New Testament context.

In a more nuanced earlier study, The Economy of the Kingdom: Social Conflict and Economic Relations in Luke’s Gospel (1988), Halvor Moxnes utilises

many of the same theorists to provide an analysis of Luke’s presentation of Jesus’ approach to the economic relations of the peasants with the

elite in his gospel. He begins his study by observing that the Pharisees are characterised as philarguros and seekers for epainon and doxan,

arguing that these terms are part of a topos concerning leadership linked to patron-client relations. Prominent in his study is the concept of the

embedded economy, based on Karl Polanyi, Trade and Market in the Early Empires (1957) as modified by M. Granovetter (1985). This analysis argues that

economic activity in the premodern era was subordinate to the norms, values and goals of the ‘moral universe’ of particular cultures and that

economic activity was constrained by these to the extent that economic profit was not the prime goal of economic activity. Polanyi’s famous ‘double

movement’ argues that in the modern era the economy has escaped from its embeddedness in the moral and social order to become autonomous and then in turn

to colonise the moral and social order, so that in the end everything else is embedded in the new market system.1 However, in the ancient world, the

market and the accumulation of capital do not operate independently of social and cultural factors, as ‘the social and economic exchange was embedded

in a highly meaningful context of cult and ritual, linking the mundane to the transcendental’ (Moxnes 1988:38). Profit is not the primary motive in

economic activity for the elite but rather honour, expressed by the ‘conspicuous consumption’ of the elites (Moxnes 1988:40). Increased productivity

is not the way in which wealth is accumulated but rather the acquisition of land. Moreover, in a ‘limited goods’ culture, it is assumed that a

person can only accumulate wealth by depriving others of the same, often by conquest and redistribution of the spoils of war in exchange for loyalty in a

system of imperial patronage. The elite were more concerned with status and expansion of land holdings than accumulation of capital, whilst the peasants

were concerned with survival and the maintenance of the social and moral order. This is the understanding of a ‘moral economy’, which is adopted

in this article. Particularly suggestive in Moxnes’ analysis is the study of patron-client relations and their control of economic exchange in Luke’s

Gospel, based especially on Eisenstadt and Roniger (1984), Patrons, Clients, and Friends. This will be explored further in this article.

What is surprising is that, even though the relationship of Didache to the ‘Q’ tradition is widely acknowledged (even if some attribute

it to use of Matthew), little attention has been paid to the economic relations of the Didache. As most of the ‘Q’ texts cited by

Horsley to build his picture of the moral economy of ‘Q’ are found also in the Didache, one would expect this to be an enlightening

point of comparison, particularly because the Didache seems directed towards Gentiles, at least in terms of initiation. Is the moral economy of

‘Q’ maintained and still understood in the Didache’s ‘redaction’ (if ’Q’ was actually a text, rather

than an oral tradition as I would maintain) and how is it further developed? What are the dimensions of its embedded economic relations? A further

point of interest would be whether the ‘moral economy’ is found only in the Jesus tradition in 1:3–6 or whether the Didache

as a whole presents a consistent picture of economic relations. The economic relations in scholarly discussion of the Didache have only

really become prominent in relation to tithes and whether the community behind the text is rural or urban (Schˆllgen 1985).

|

Aaron Milavec: The economic safety net

|

|

A notable and commendable exception to this is Aaron Milavec (2003:173–227), whose commentary has an extensive section on economic relations in the

Didache, which he titles, ‘The Economic Safety Net’. Although he does not use the terminology of the ‘moral economy’ and

is more dependent on the Marxist analysis of GEM de Sainte Croix (1981), it does enter his discussion implicitly through his use of J. Dominic Crossan

(1989, 1998). Milavec rightly notes that ‘economic training occupies over one-third of the Way of Life’ because in a system of patron-client

relationships ‘someone entering into a new religious movement might urgently need a new set of commercial alliances to replace those that would

inevitably be ruptured by his or her new religious commitments’ (Milavec 2003:176). Before examining his hypothesis, it should be noted that

Milavec’s discussion presupposes a number of hermeneutical moves. Firstly, he rejects source criticism or any literary relations between Didache

and the canonical gospels and so presupposes a very early date. Secondly, he sees the work as a unitary, oral catechetical composition for prospective members

of the community, reflecting a ‘pastoral genius’ in which information is delivered sequentially through oral performance according to the programme

of initiation. Thirdly, he presupposes rather an urban, ‘working class’ rather than a rural setting. As this supposed environment is the basis for

his analysis of the economy of the text, it is important to examine his grounds for this assumption.

Milavec advances three arguments. Firstly, whilst Didache 1:5 requires one to give to anyone who asks, without question and without asking for

it back, Didache 4:6 qualifies this by saying, ‘If you have anything through your hands, give a ransom for your sins’, so that the

context for the existence of a surplus must be manual labour. This is a rather weak argument, because the expression ‘through your hands’

need not be taken literally nor as a reference to manual labour. In Hebrew and Aramaic, the expression beyad comes to

mean simply ‘by means of’. It could also refer to trade, one assumes, or teaching for that matter. The principle, ‘let him work and let

him eat’ (Didache 12:3) is extended to the prophet and teacher since he ‘is worthy just as the worker of his hire’ and is used to

justify payment in cash and kind of prophets and teachers in Didache 13:1.

Secondly, Milavec points to the widening of first fruits to bread making, opening wine or oil, silver, clothing or any possession (Didache 13:5–7).

However, this is again not a strong argument; Georg Schˆllgen (1986) has already shown the fallaciousness of this conclusion:

• agrarian products form only one member of a four membered literary structure in which first the raw and then the processed products are mentioned and not

every first fruit is expected of every person – they are simply examples of the duty to support the prophets

• the widespread legal requirement of first fruits is probably post-Constantinian and in Hippolytus the same rural products are specified for great

cities like Rome, which are not predominantly concerned with agriculture

• both agrarian produce and its processed forms are available in both country and city – the majority of whose inhabitants typically worked

the surrounding lands.

Thirdly, Milavec argues on the basis of the permission in Didache 12:3 for those with a craft to settle (‘let her work and let her eat’)

that members of the Didache community were ‘neither freeloaders nor rich’, neither exploiters nor exploited, nor poor without skills (‘They

were not living a hand-to-mouth existence that opened them to random acts of exploitation’) (Milavec 2003:181). However, this unproblematic case is

supplemented by a second category: those who wish to settle but who do not have a craft. They must also be taken in by the community, as long as they do not

live an idle life (Didache 12:4). Presumably, many of them would have been peasants or day labourers in the surrounding fields, since this class

formed the majority of a city’s inhabitants. Whilst an urban origin is not unlikely, it cannot be proved any more conclusively than a rural one on this basis.

This makes the anachronistic language about the ‘urban working class background presupposed by the membership of the Didache communities’

(Milavec 2003:183) problematic, in my opinion. Whether it was urban or rural, it is likely to have been diverse. Elite or non-elite, slave or free(d) (wo)man,

peasant or artisan, male or female, rich or poor are perhaps better terms than ‘upper class’ and ‘working class’, with its modern

baggage, particularly since Milavec envisages these working class folk owning slaves and having large workshops; excavations from Ostia indicate that the

urban poor lived in extreme squalor and cramped conditions in the insulae (the crowded tenament apartments inhabited by the urban poor; see

Wallace-Hadrill 2003). Certainly, the more prosperous artisans may have bought slaves to assist them, but then ‘working class’ ceases to apply

in any meaningful sense. Fundamental, however, is the question of whether the Didache reflects the background of a peasant village in Galilee from which,

as argued by Horsley and many others, the ‘Q’ source emerged as a programme for renewal of community. This seems to me extremely unlikely, because

the teaching is orientated towards Gentile converts (at least in its present form it constitutes ‘Teaching of the Lord through the Twelve Apostles to the

Gentiles) and envisages numbers of outsiders coming into the community. Peasant village communities, on the other hand, are notoriously closed and cautious about

outsiders. This is not to say that there are no elite representatives or outsiders in such rural peasant villages, but that those that are there remain outsiders,

no matter how long they live there. Renewal movements for Horsley are reformulations of the Great Tradition of the culture from the perspective of the Little

Tradition (Scott). Whilst the Didache certainly reflects the cultural tradition of Israel, its debates seem close to the debates of the Pharisees,

representatives of the Great Tradition, whom it sees as its rivals (the ‘hypocrites’ mentioned in Didache 8:1−2). Moreover, adherence

to the ‘great tradition’ of the Torah is made optional for gentile members of the community: ‘if you can bear the whole yoke [of the Torah]

you will be perfect, but if you can’t bear what you can’. The kind of proselytising movement implied by this text seems to me best placed in a situation

at the crossroads of peoples and cultures and hence most probably in an urban setting, rather than a homogenous peasant village.

According to Milavec (2003), the whole of Didache 1:3–6 applies to outsiders to the community, so that the catechesis begins with a requirement

that prospective members sacrifice honour, labour and goods to outsiders without any question about their worthiness and without limits. This is to rid them of

the habit of economic productivity and teach them to imitate the free giving of God who is the true goal of the act of giving:

The absence of any grounds for inquiry in the Didache suggests that the ‘expressed need’ of the petitioner overrides the right of the giver

to examine the one asking in cases involving food or clothing. (Milavec 2003:186)

The examination of the worthiness of the petitioner is reserved to the final judgment (Milavec 2003:186). I have suggested elsewhere (Draper 1997:58) that

such unreserved giving would lead to penury for new community members and would have placed an ‘enormous strain upon the community resources’.

Milavec argues, however, that there must have been ‘a natural limit to the unrestrained giving’ (Milavec 2003:197) and that the converts’

families would have continued to support them with food and accommodation even if they withheld access to resources to give. If there was a danger, Milavec

argues, then ‘in practice, the spiritual mentor undoubtedly intervened in order to moderate or entirely set aside the first rule’ (Milavec 2003:198).

There is, however, no evidence for either of these assumptions in the text and they would seem to undermine Milavec’s main argument.

Milavec sees Didache 4:5–8 as applied only to insiders, because it is not now a matter of unreserved giving but of reciprocity. A new modified

form of unreciprocated giving continues, but now such almsgiving is seen as a ransom for sins in the face of the imminent arrival of the Lord. Milavec argues

here that the new members would have faced ‘ruination and be forced to join Christian collectives‘ (Milavec 2003:210–211), but this contradicts

his earlier insistence that unrestricted giving would be suspended by the convert's mentor before it led to financial disaster. He argues that koinonia

refers not to fellowship but to business partnerships, which were at the heart of the Christian economic safety net:

In the ancient world, an entire family normally practiced a trade together working side by side in the same workshop.... [Where anyone other than the head

of the family became a Christian] ’one might expect such “deviants“ to be expelled from the family business and disinherited. Those expelled

were effectively “dead” both socially and economically, for in that moment they would be cut off from their biological family and from their family

livelihood as well. With baptism, such persons were reborn as children of their Father in heaven and gained a new family. Accordingly novices who were ousted

from their family’s business joined with the new family and thereby maintained themselves and their dependents by working at their craft. It was in these

“new” families that everything was shared just s it had been in their former biological families. Even in the case of visitors who decided to settle

into a Didache community, the operative rule was “let him /her work and let him/her eat” (12:3)—the presupposition being that any Christians

would be immediately employed in the “family” businesses within the local community’. (Milavec 2003:210−11)

This interesting hypothesis undoubtedly has some merit and may well have been an important aspect of the social life of many community members, having support

in the practice of Paul, but there seems insufficient evidence in the Didache to put so much weight on it. The only argument Milavec advances is the

supposed meaning of koinonia as a reference to workers’ guilds rather than to community of goods (see Draper 1988).

Finally, Milavec argues that the Didache community rejected the patron-client system of the ancient world, seeing God as the sole patron (based on

Didache 3:9–10). Freed in this way ‘from the patronage of men’ and from the necessity of attendance at pagan festivals and other

compromising associations to please powerful patrons and secure their economic position (Milavec 2003:224−225), members instead entered empowering

and honest economic partnerships with each other. No doubt they did so, but in this they would be following a well-worn track in the business associations,

funeral societies and kyrios or kyria cults of dying and rising gods and goddesses in the ancient world, such as those of Mithra, Isis and

Osiris, Dionysis and Orpheus. What Milavec leaves out of account is the likelihood that better off or well-positioned members of the Didache community

would have been expected to act as brokers and patrons for the benefit of the community and its members and received honour as a reward, as I have argued

elsewhere (Draper 1995). Overall, Milavec’s hypothesis is an interesting exploration of possibilities in the text, but perhaps rather inclined to

romanticise the community relations.

|

The moral economy of the Didache

|

|

Perhaps we should begin with the model of reciprocity and redistribution, which Moxnes uses in his analysis of the moral economy of the Kingdom

in Luke, based on Sahlins’ Stone Age Economies development from Polanyi’s model of reciprocity, redistribution and market exchange.

He sees three forms of reciprocity based on ‘span of social distance’:

• generalised reciprocity (exchange is altruistic or a pure gift – in theory at least)

• balanced reciprocity (seeks ‘a near-equivalence in goods and services’)

• negative reciprocity (trying to get something for nothing by violent or other means).

Close kin incline to forms of reciprocity based on social proximity, whilst strangers and outsiders incline to the general and balanced

reciprocity. It may not seem obvious at first to view the instructions in the Didache as a system of redistribution. However, in

the ancient world ‘the social and economic exchange was embedded in a highly meaningful context of cult and ritual, linking the

mundane to the transcendental’ (Moxnes 1988:38). The Didache clearly does provide a system which is both continuous with and

provides an alternative to the norms of the surrounding society. Whilst redistribution serves a practical function of logistical redistribution,

its greater purpose is social bonding, that is, a ‘double effect of redistribution and its embeddedness in the most central aspect of a

common culture’ (Moxnes 1988:39).

In the first centuries CE, the Roman empire had created a vast system of asymmetric redistribution with itself at the centre, which impoverished

and subjugated its client states, but which also promised reciprocal benefits (however illusory) namely security, peace and infrastructure. The

central institution in the social model of exchange was that of patron-client relations, with the emperor as the chief patron and a network of

brokers radiating outwards and downwards through myriads of local brokers who mediated access to power, privilege and hence to material resources.

This has been well described by Moxnes and many other scholars working with the social sciences and the New Testament (NT) (e.g. Malina 1981; Neyrey

2005). The patron-client system cemented bonds of unequal relations, which were also patriarchal and gendered. Women and slaves were at the bottom

of the pile, although elite women had negotiated some position of relative autonomy and privilege. Some classicists have even spoken of the ‘new

Roman woman’ (Winter 2003).

This patriarchal network was legitimated by a social and religious order which projected a cosmic symbol system of stability and ‘nature’

underpinning the systematic exploitation of the under classes whilst obtaining their acquiescence. However, as Moxnes has pointed out, this system was

contested continuously and challenged by the underclass, so that there was a constant tension with its claims to be the God-given and unchangeable order

of nature. Patron-client relations were thus ‘not stable and continuous, but rather characterized by change and lack of stability’ (Moxnes 1988:45).

If we try to chart the economic relations in the Didache against this background, we come up with in Table 1.

|

TABLE 1: Reciprocity and redistribution in the Didache.

|

God as Patron

Let us proceed to analyse Table 1. Firstly, we can observe that God’s role is ambivalent. God acts on the one hand as a typical patron in the

patron-client system: as Sahlins points out, the ‘chieftain’ is expected to give generously, often with handouts of food, in exchange for

honour. God acts in this way, giving life, food and drink generously to all in order that they may love and praise him. God also requires loyalty on

pain of loss of favour and punishment. God requires community members to give freely also in imitation of him, but such giving is really giving to

God and will be rewarded by him by forgiveness of sins. On the other hand, God breaks the unwritten code of patron-client relationships in blessing

and giving spiritual food and drink and eternal life free to members of the community. He protects the poor and needy and works in all things for the

good of all rather than for gain. However, the great patron of the 1st century world was the Roman emperor, who claimed to be doing the same things!

Yet, a key factor is that God has no favoured ‘clients’. God does not favour those who can give back more than others can. Indeed, before

God masters and slaves share the same status (4:10); it is possession of the Spirit which God sends that determines their status before God. As a result,

there is a difference in the genuine sharing of resources required of members of his community to all who ask good and bad in response to his gifts.

God judges justly and requires just judgement and righteousness from community members without favouritism, double standards or prevarication (4:3–4;

3:9), so that the skewed justice of the patronage system is forbidden within the community.

Community members

The fundamental rules of community life are based on the Old Testament (OT) norms: love God, love of neighbour as the self and do not do to others

what you do not want them to do to you. This could be interpreted as a balanced reciprocity: if it is contained within the family or community as a

kinship relationship, real or fictive, where one could expect or even enforce a mutual adherence to these principles. However, the addition of the

‘Q’ tradition in 1:3–6 as an interpretation of these basic rules transforms it into a requirement to practice generalised reciprocity:

the rules apply to relations with outsiders who behave with negative reciprocity towards them – enemies who hate and persecute them, shaming them

with dishonourable violence, impressing them into forced labour and seizing their possessions (even their clothing). Yet not only are community members

to practice non-retaliation, they are to reflect the shame back onto their persecutors by going beyond what they are required to do: turning the other

cheek, going two miles when commanded to go one and declining to ask for anything back when it has been forcibly seized! Furthermore, they are to give

to everyone who asks without asking for anything back, an attitude of generalised reciprocity without expectation of profit or material benefit. However,

they do receive the balanced reciprocity from God of knowing they give to God and that he will reward them and remove their sins (1:6, 4:7).

A tricky question is whether the required act of giving in Didache 1:5–6 is intended to be to all outsiders good or bad, right or wrong, or

primarily to insiders. The problem is that unrestricted giving of this kind would impoverish and ruin any community. As we have seen, Milavec argues for

this interpretation and I have also done the same elsewhere (Draper 1997). On the other hand, he sees this as only required during the period of initiation,

which does not seem likely to me. Moreover, the instructions do raise the question of need (χρεία, twice in 1:5). The target of

giving in Didache 4:8 is the needy person [τὸν ἐνδεόμενον], which is synonimous

with ‘having need’ [χρείαν ἔχων]. In Didache 11:5 an exception to the rules on hospitality

to apostles is grounded on the same principle of need [χρεία] as the fundamental principle of giving and receiving based on

their overriding sense of justice – a prime hallmark of the kind of peasant moral economy described by James Scott. Again, the needy person arriving

in the community without any skills to support him or herself is to be assisted as far as possible – although the word is not used this time –

provided that the person does not live idly and exploit the community’s provision (Didache 12:4). Members are required to give freely with God

as the goal of their giving, the God who wishes to give to all out of his own gifts (given in the first place to the community members in trust). In my opinion,

Didache 1:3−4 provides a rule for conduct to outsiders, whereas Didache 1:5−6 provides rules of conduct to insiders. My reasoning is

based on the provision in Didache 1:5 that the one taking without need would have to give account and, being in distress

(συνοχή, the word does not mean ‘prison’, except by extension), would not get out of there until she or he

had paid back the last farthing. In the Matthean (5:26) and Lukan (12:59) versions of ‘Q’ the word used is specifically called

φυλακή and it follows the advice that one should be reconciled with one’s accuser whilst on the way lest she

or he press a charge and one winds up in debtor’s prison. However, in Matthew the context is that of a quarrel with one’s brother

(πρῶτον διαλλάγηθι τῷ ἀδελφῷ

σου 5:24). Milavec assumes the reference in the Didache to be a reference to eschatological judgement, but there seems no

justification for this. It seems that, whilst none was allowed to refuse a request for assistance, anyone taking advantage of this principle to accumulate

wealth would face some kind of community investigation and if found guilty would face some kind of retributive justice, whether it was actually prison or

not (it would more likely be exclusion from the community), until they had repaid the full amount. It seems unlikely that this principle could be followed

through in civil courts against outsiders, but very likely it could be undertaken against community members (‘you shall judge justly’,

Didache 4:3). In this case, it might indicate that Didache 1:6 (‘But indeed concerning this it was also said, “Let your alms

sweat in your hands until you know to whom you give”’) refers to a human supplicant and not to God and that the supposed reference to Sir.

12:1 is a red herring (it is, in any case, equally slippery). Then it would mean, ‘don’t give to someone who abuses the trust’ and puts

a limit on the principle of unreserved giving which is stated at first. Of course there is a long debate about this, well set out by Milavec. The sense of

Didache 4:6–7 implies that the giving of alms is ultimately to God and that it is rewarded by the atoning of sins, and 1:6 could also be taken

in that light.

The instruction in Didache 4:5–8, in any case, has far more of the familiar feel of the kind of ‘redistribution’ advocated by

Jesus, where people in the villages of Galilee in a time of economic crisis are urged to the solidarity of resistance against the crushing effects of

Roman imperialism, where they are called to forgive the debts of their neighbours in view of their own debt to God, to give to those in need without

requiring it back, to invite the hungry to their tables and not the well off and so on. You must not stretch out the hand to receive but shut it when

it comes to giving (Didache 4:5); if you have earned a surplus give (Didache 4:6). What is highly significant is the legititmation provided

for the giving here. It is not simply village reciprocity or redistribution to guarantee the survival of families in the village, but rather it is seen as

a sign of a new kind of spiritual community. Members of the community are already κοινωνοί in immortal things,

so how much more should they share with one another in the material things. This is the basis on which they should call ‘nothing their own’.

In the Greek patron-client culture, the principle is that κοινωνία [communion] is only possible where there

is ἰσότης, that is, between friends who are equal in rank and wealth since otherwise there

would be a debt between them (see Draper 1988). The Didache turns this principle on its head, making all members of the community equal

on a spiritual basis, and so sharing everything in a material fellowship with each other

[συγκοινωνήσεις] as equals. The argument runs qal wa homer

[‘from light to heavy’] in Rabbinic fashion, but it is directed against the Hellenistic principle of ‘sharing between

[social and material] equals’.

Other forms of general reciprocity, which fit into the category of a moral economy, were the weekly communal meals, which were full meals

(μετὰ δὲ τὸ ἐμπλησθῆναι 10:1) shared by

all, including the poor and needy. The effect of this should not be minimised, as normal weekly rations for the poor would probably be close

to starvation rations, whilst this would imply a meal with meat and wine. Secondly, travellers belonging to the Christian movement of all

description, whether religous functionaries like apostles and prophets or ordinary travellers, are to be welcomed and provisioned whilst they

travel, though they may only stay for a day or two and may not ask for money. But they may also settle, even if they do not have a trade to

support themselves. The community must make a plan! Milavec’s suggestion that they might have been taken into the workshops of Christian

craftsmen has no evidence to support it, but is a likely senario for some of those who wished to settle, especially if they already had a skill.

However, the wandering poor probably included those peasants who had lost their land through debt or war, or who simply walked off it

– ἀναχωρήσις – and who now wanted to settle in the community. Whilst

this may not have been an option in every case, the Christian κοινωνία clearly involved making

plans to integrate them into the material and social life of the community, as they were not to remain idle (Didache 12:4). Most

probably, such peasant refugees would also have been drawn into the task of tending and harvesting the fields of those members who were

agriculturalists as day labourers or as members of extended households sharing roof, board and labour. Thirdly, the community reserved the

first fruits for the poor, if there were no prophets (Didache 13:4). This may often have been an important means of redistribution

in the community, particularly as it may have grown in size and prosperity and particularly if prophets began to be thin on the ground.

Fourthly, prophets might order a meal or table for the hungry (Didache 11:9 – even if we consider it a eucharist it amounts

to the same thing, as it was a full meal) or might ask the community to give money or goods to the needy, the poor and inferior

(περὶ ἄλλων ὑστερούντων

Didache 11:12); in both cases the prophet was not allowed to share in what he prescribed.

Prophets and teachers form a particular category within this moral economy. Both may be remunerated after they have been tested and found true,

probably on the basis of reciprocity for the spiritual work they did, since the instruction on the legitimacy of provisions for the prophets and

teachers come after the statement of the principle: ‘Let him/her work and let him/her eat’ (Didache 12:3). The allocation of

first fruits to the prophets is interesting in itself (see Draper 2005). It is appropriate since first fruits were not required on what was produced

outside of historical eretz Yisrael [the ‘land of Israel’, the land of covenant which bound Israel to fulfil the Torah and to give

the land’s first fruits to the God of the covenant], but were still felt to be an obligation, even by those who may have been paying temple

tax as Jews to the Romans through the local Jewish communities. In the Holy Land they were offered to local priests when it was not possible to get

them to the temple (because perishable), and the principle is extended here to the prophets as the ‘high priests’ of the new community

– particularly appropriate one imagines after the demise of the temple in 70 CE. Nothing is said about how the teachers were to be remunerated,

but one imagines that it would have been by the catechumens they instructed. This was certainly how it was understood in the Ecclesiastical Canons and

the Epitome, other Christian versions of the Two Ways. If the Lord gave the catechumens spiritual food through the teachers, how much more should they

give material food back to them.2

Whilst the prophets and teachers were remunerated in a Reciprocal Distribution manner, they also received honour which technically should be due

to patrons of the community for their benevolent General Reciprocity to the community. In a way, they were getting something for nothing in this

case, in other words Negative Reciprocity. These patrons are indicated by the key words in patron-client relations (Draper 1995):

ἀφιλαργύρους, λειτουργία

and τιμή (Didache 15:1–2). Moxnes has argued at length that these words were part of a trope

concerning appropriate leadership or patronage in the ancient world. They are not to be lovers of money, not just because they should

not be corrupt, but also because they were to be benefactors of the community, ‘generously’ making their resources available

for the public good in what was called their leitourgia [‘public service’]. They were to be humble, not because they

were to be diffident men, but because they should not be seen to be scrambling for power and position. So bishops and deacons are to be

chosen as patrons of the community with the expectation that they would be able to offer the community resources and protection and probably

their houses to meet in on the ‘Lord’s day of the Lord’. What they could expect in return was honour and loyalty. In this case,

however, the prophets and teachers were not only receiving money and resources but were also the recipients of honour and loyalty – their

paid work being considered a leitourgia, such that the bishops and deacons were being despised (Didache 15:2). It is not

surprising that this produced problems in the community. The Didache settles the matter by arguing that all of them – prophets and

teachers, bishops and deacons – should receive the same honour for their work. One wonders how long such a compromise could have survived –

not long it seems, since bishops and deacons subsequently surplanted prophets and teachers completely in the emerging church!

Housetables

Finally, we need to recognise that the koinonia of the equals envisaged by the community had some elements of negative reciprocity: chiefly

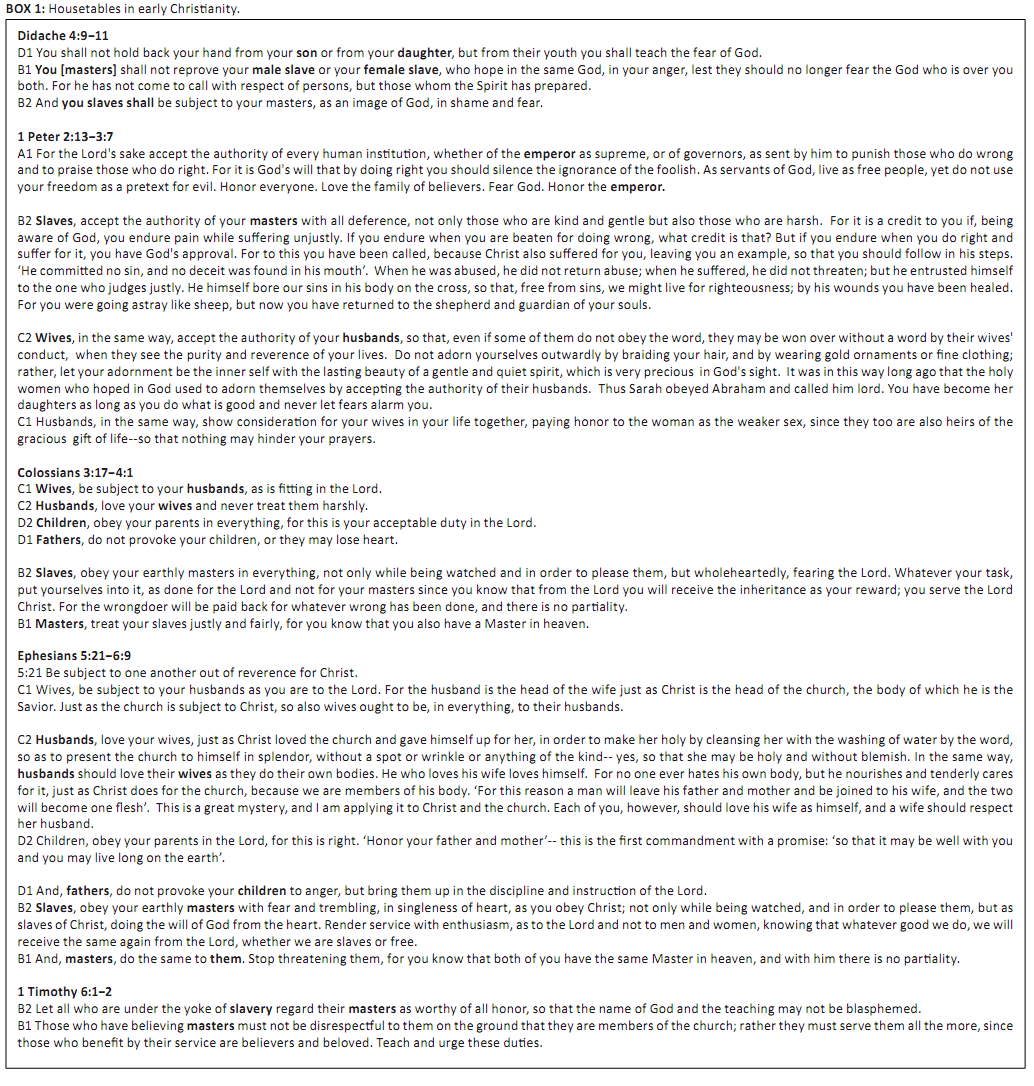

in the Christian table of household behaviour or the Housetable in Didache 4:9–11, which is significant both for what it says and what

it does not say. The underlying schema, tracable in the table of NT exemplars and probably deriving from Hellenistic Judaism, seems to have four

reciprocal components regulating social relations with the state (A1/2), masters and slaves (B1/2), husbands and wives (C1/2), parents and children

(D1/2). The Didache has only two elements, one a single element of parent (D1, probably the pater familias is intended), the other a

balanced couplet of slavemasters and slaves (B1/2). In any event, the Housetable ties the egalitarian koinonia of equals into the extremely

unequal patriarchal structures of the ancient world. 3 The text which follows is arranged with the Didache text first, followed by

texts in a roughly chronological order (in my reckoning).

It can be seen immediately that whilst the core components of the Housetable are remarkably consistent, they are not all utilised in any one of the

lists below at the same time. The table should ideally be constructed of a set of four couplets, comprising the mutual responsibility of the senior

and junior partners (in terms of status and power): emperor or subject; master or slave; husband or wife; parent or child. However, not all the units

A−E are included in any of the texts nor do all of them have the mutual components 1−2, nor do they occur in the same order. The inclusion

or exclusion and order of any of the units clearly depend on the social and economic priorities or problems experienced by each community. Hence they

offer important information on the moral economy of each early Christian community which produced them.

|

BOX 1: Housetables in early Christianity.

|

|

Only one of these tables mentions honouring the emperor, which probably belongs to the Hellenistic Jewish substratum of the Housetable. Its omission

from most of the Christian tables, including the Didache, is not surprising given the claim of the Caesar to be the ‘son of God and high

priest‘ or even dominus et deus. However, the words ‘husband’ and ‘wife’ occurring together is remarkably constant

and its absence in the Didache indicates that the community may well have had women who were not subject to husbands (widows or other female headed

household) or whose husbands were hostile unbelievers who might have forbidden their wives from joining the Christian community (in which case commanding

obedience would have been counterproductive). Secondly, those tables, which mention the parent or children relationship, include instructions to both

parties. That Didache mentions only the responsibility of the (father) parent to punish corporally the children into the faith and not the rights

of the children to fair treatment. This may indicate problems in a family when the parents converted to Christianity and the children did not (bearing

in mind even adults would still be subordinate to their pater familias). Moreover, the long instruction to the slave owner not to mistreat the male

and female slaves, as was common practice, indicates that this was a problem in the community. Owners are so harsh that there is a danger that slaves may

cease to believe, particularly because they would have been required to join the community when their owners converted. They would have understood the

koinonia of the new community of faith to have altered their status to that of equals. The Didache settles this by acceding their equality

before a God who has no favourites, but then re-establishing the patriarchal hierarchy with particularly poignant religious legitimation: the owner is a

typos of God to whom they must be subordinated ‘in shame and fear’ (Didache 4:11).

The food market

Although space is limited (and I have written on it elsewhere, Draper 1991, 2003), the requirement that new members commit themselves to

observe as much of the Jewish food law as they are able to and to keep strictly from eidolothuton [‘food offered to idols’],

has significant economic consequences (Didache 6:3). It would force them out of the normal food markets, where virtually everything has

been offered to the Graeco-Roman gods at some stage or another. It would force members of the Didache community into the alternative market

systems of the Jewish communities in the Mediterranean world, where food could be known to be kashrut (food originating and prepared in

accordance with the food laws in the Torah). Alternatively, they would buy food and drink only from other members of the community, if it was

large enough (much as the Pharisaic communities or haburoth used to do). This, in my opinion, is one of the reasons that Paul is willing

to relax this condition (1 Cor 10:25−31). He only prohibits his communities from eating meat and drink that they have been told has been

offered to the gods (do not ask, do not tell). However, in the Didache communities, the requirement to keep strictly from food offered

to idols would encourage economic solidarity and an exit from the markets they previously frequented as gentiles.

Outsiders

Outsiders are mainly characterised by Negative Redistribution, taking goods, labour and honour from members of the community without recompense,

something for nothing (Didache 1:3–6). Unsurprisingly, they are the reverse of community members. Those walking on the Way of Death (5:1),

besides breaking the Ten Commandments are guilty of the economic behaviour characteristic of the imperial system: thefts [klopai] and rapines

[harpagai]. Their conduct matches that of the patrons and brokers with which the poor in the ancient world were very familiar: ‘jealousy,

over-confidence, loftiness, duplicity, deceit, haughtiness’ and, above all, acquisitiveness [pleonexia]. They do not recognise the

‘reward for righteousness’, namely the goal of all things in God. The poor are at their mercy as they are both exploiters and unjust

judges who protect their own elite class. They are those who oppress the poor and pervert justice in favour of the rich:

Those sleepless not for good but for evil; those from whom meekness and perseverence are far; those loving vain things; those pursuing bribes. Those

not having mercy on the poor: those not working hard to aid the down trodden those not knowing the One who made them: murderers of children, corruptors

of the creation of God. Those who turn away the needy, those who tread down the oppressed: advocates of rich people, lawless judges of the poor. Those

altogether sinful. (Didache 5:2)

Just as the patrons of the Didache community were characterised as aphilarguros and praus [‘not lovers of money’

and ‘meek’], so the patrons outside the community are philarguros and kenodoxos (‘lovers of money’ and ‘

vainglorious’, Didache 3:5), treacherous liers whose pseusma [‘lying’] leads to theft, the exploitation and plunder

of the weak and the poor. Such people are excluded from the community’s meal and from their hospitality (Didache 9:5).

Our brief and rather tentative study of the moral economy of the Didache has confirmed that it functions as an alternative economy to the

exploitative and oppressive patron-client networks of the ancient Roman Empire. God is seen as the only true patron protecting and providing for

the community in exchange for love and praise. There is an element of ambiguity here: if God provides in exchange for praise, this is practising

balanced reciprocity; on the other hand, on the other hand, if God does it as a free gift, God practices generalised reciprocity. Emulating the

God who ‘wishes to give to all out of their own gifts’ (Didache 1:5), the Didache puts in place a system of general

redistribution that would not allow the poor in the community to fall into ruin and starvation. It provides hospitality and refuge for members

who are travellers or refugees from other communities and come ‘in the Name of the Lord’. The koinonia tou hagiou [communion

of the saints] is very much an economic system for those who join the community and thus pool their labour, goods and services for the common good.

It also spills over into open rejection of the Roman system in the public sphere by refusing to resist the seizure of money, goods and honour (acts

of negative reciprocity) whilst simultaneously challenging the honour of the system by voluntarily doing extra (and so practising generalised reciprocity).

They would also begin to buy their food and drink from different markets. This cements the solidarity and in-group interaction of the new eschatological

Christian community. In broad outlines, then, this study affirms Aaron Milavec’s claim that the Didache provides an economic ‘safety

net’ for its members. However, contrary to his depiction, I would argue that this would not be only by means of cooperation between artisans in

workshops, as the community would have had members in all kinds of economic situations, including slaves, wives of unbelievers, agricultural workers

without skills, teachers and wealthier members who could act as patrons.

Furthermore, we should avoid minimising the inherent contradictions or weaknesses in this social and economic ‘safety net’. The Housetable

regulations continue to hold the slaves under the strict regulation of their masters, with an added religious sanction, and children are required to

convert and remain faithful to their parents’ newfound faith. Furthermore, whilst prophets and teachers are given honour though they are drawing

on the resources of the community, a contradiction of the patron-client expectations, the community does make use of well connected and better off patrons,

who should be aphilarguros [‘not lovers of money’] and share their wealth and houses as their leitourgia [‘public

service’] and be rewarded with honour. These two factors provide an ambivalence and potential point of conflict in the community and open it

up, in the long run, to re-colonisation by the Roman patron-client system and imperial exploitation.

Crossan, J.D., 1991, The Historical Jesus: The Life of a Mediterranean Jewish Peasant, Harper, San Francisco, CA.

Crossan, J.D., 1998, The Birth of Christianity: Discovering What Happened Immediately after the Execution of Jesus, Harper, San Francisco, CA.

De Saint Croix, G.E.M., 1981, The Class Struggle in the Ancient Greek World, Duckworth, London.

Draper, J.A., 1988, ‘The Social Milieu and Motivation of Community of Goods in the Jerusalem Church of Acts’, in C. Breytenbach (ed.),

Church in Context, pp. 79−90, NGK Boekhandelaaar, Pretoria.

Draper, J.A., 1991 [1996], ‘Torah and Troublesome Apostles in the Didache Community’, Novum Testamentum 33(4), 347−372; reprinted

in J.A. Draper (ed.), The Didache in Modern Research, pp. 340−363, Brill, Leiden.

Draper, J.A., 1995, ‘Wandering Radicalism or Purposeful Activity? Jesus and the Sending of Messengers in Mark 6:6−56’, Neotestamentica

29(2), 187−207.

Draper, J.A., 1997, ‘The Role of Ritual in the Alternation of Social Universe: Jewish Christian Initiation of Gentiles in the Didache’,

Listening 37(2), 48−67.

Draper, J.A. 2003, ‘The “Yoke of the Lord” in Didache 6:1−3 as a Key to Understanding Jewish-Christian Relations

in Early Christianity’, in P. Tomson (ed.), The Image of Judaeo-Christians in Ancient Jewish and Christian Literature, pp.

106−123, Mohr Siebeck, T¸bingen.

Draper, J.A., 2006, ‘Jesus’ “Covenantal Discourse” on the Plain (Luke 6:12−7:17) as Oral Performance: Pointers to

“Q” as Multiple Oral Performance’, in Oral Performance, Popular Tradition, and Hidden Transcript in Q, pp.

71−98, ed. R.A. Horsley, Scholars, Atlanta/Brill, Leiden. [Semeia Studies]

Eisenstadt, S.N. & Roniger, L., 1984, Patrons, Clients, and Friends, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Horsley, R.A., 2008, Jesus in Context: Power, People, and Performance, Fortress, Minneapolis, MN.

Horsley, R.A. & Draper, J.A., 1999, He who hears you hears me: Prophets, Performance, and Tradition in Q, Trinity Press International, Harrisburg.

Malina, B.M., 1981, The New Testament World: Insights from Cultural Anthropology, John Knox, Atlanta, GA.

Milavec, A., 2003, Faith, Hope, and Life of the Earliest Christian Communities, 50-70 C.E, Newman, New York.

Moxnes, H., 1988, The Economy of the Kingdom: Social Conflict and Economic Relations in Luke’s Gospel, Fortress, Philadelphia, PA.

Neyrey, J., 2005, ‘God, Benefactor and Patron: The Major Cultural Model for Interpreting the Deity in Greco-Roman Antiquity’,

Journal for the Study of the New Testament 27, 465−492.

doi: 10.1177/0142064X05055749

Polanyi, K., Arensberg, C. & Pearson, H., 1957 [1971], Trade and Market in the Early Empires, Henry Regnery, Chicago, IL.<

p>

Sahlins, M., 1972, Stone Age Economics, Aldine, Chicago, IL.

Scott, J.C., 1976, The Moral Economy of the Peasant, Yale University Press, New Haven, CT.

Scott, J.C., 1985, Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance, Yale University Press, New Haven, CT.

Scott, J.C., 1990, Domination and the Arts of Resistance, Yale University Press, New Haven, CT.

Wallace-Hadrill, A., 2003, ‘Domus and Insulae in Rome: Families and Households’, in D.L. Balch & C. Osiek (eds.),

Early Chrstian Families in Context: An Interdisciplinary Dialogue, pp. 3−18, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, MI/Cambridge, MA.

Winter, B.W., 2003, Roman Wives, Roman Widows: The Appearance of New Women and the Pauline Communities, Eerdmans, Cambridge.

|

|