|

This article proposes that the notion of liturgical space, understood in conjunction with the original Greek concept of space, is not only a quantitative, physical locality, but also a primary qualitative possibility for existence, a meaningful womb, a neighbourhood for imagination and a space for anticipation. Threeconsequences of this proposal are discussed, namely liturgy as waiting on the elusive presence (presence of absence) of God, celebration as (metaphorical) dance of hope, and the need for liturgical refiguring.

The famous play, Waiting for Godot, by Samuel Beckett, has become iconic for depicting people who are waiting for nothing.1 Or perhaps we should say that they do expect

someone (something?) called Godot, but that he orshe orit never shows up. It is anticipation without answer; expectation without event, hope withouthappening. Time, the present, is

filled with a vacuum or at best, with depleting impatience and intolerable boredom. The play, a ‘tragicomedy in two acts’, according to the subtitle, covers two days in the lives of a pair of men waiting expectantly, but in vain. One gets theparadoxical

impression that these two men know Godot, but also not; as a matter of fact, they admit that they would not recognise him should he make an appearance. So they fill their time of waiting

with things like eating, sleeping, conversing, arguing, singing, playing games, exercising, swapping hats and contemplating suicide. In effect, they try everything to ‘kill the

time’, to counter-act the ‘terrible silence’ of waiting, up to the point where time almost kills them (cf.Knowlson 1996:57). The void of an empty present simply becomes

too painful. One is reminded of Shakespeare’s Macbeth, another tragicomedy of sorts, who boldly declares: ‘Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player that struts and frets his hour upon the stageand then is heard no more. It is a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

signifying nothing’. (Shakespeare, W., 1914, The tragedy of Macbeth, Harvard University Press, Act 5 Scene 5, lines 22–31)

|

The present of the present

|

|

Liturgy, and specifically the Eucharist, have and should have, a different take on time and on waiting. One could say that a type of condensation of the times takes place in the Eucharist: the past is presented in such a way that a yearning for the future is created, but a future that continuously breaks through into the present (cf. Van Wengen-Shute 2003:101; also Wainwright 1983:131). The Eucharist represents a form of punctual coincidence: the past and the future coincide in such a way in the present that the present becomes an epiphany, a point of revelation.2 In this regard Purcell refers to the phenomenon of ‘Eucharistic Time’, which signifies ‘the presence of Transcendence’ (2001:141−144). The Eucharist is not only a present event; it creates the present as present. It constitutes the present as a gift (a present). It interprets the present time in order to transform it into a kairos. In the same way the Eucharist does not simply signify a conjunction that connects the present with the past and the future, but it is also a gift of ‘new time’. The gift of the Eucharist ‘arises in a past covenant; it points to an eschatological future charged with hope and promise; and because of this, it establishes a present’ (Purcell 2001:141). This filling of the present, or constitution of the present through the gift or present of the Eucharist (presence of Christ), could be called infinituding. Time is filled with the infinitude;

it becomes infinitude. The presence of Christ in the Eucharist and liturgy is not so much about the description of time, as it is about theinfinituding of time and people’s experience

within this time. It is about ‘moments of eternity’, about experiences of the ‘presence of Transcendence’.

|

The presence of the future

|

|

In order for the present time to become ‘moments of eternity’, it needs to be filled with the future, and for this it needs the art of anticipation. Liturgy, as exemplified in the Eucharist, is not only about remembrance and presence, but also about (anticipation of) the future. We are called to re-tell the message of Christ’s death ‘until He comes again’ (1 Cor 11:26). Liturgy is not just about incarnation and inhabitation, but also anticipation. Obviously the future by implication means ‘not now’, the future is the future, but this is often misunderstood as an experience of time exclusively related to afuturum, that is, an attitude or mentality that somehow bypasses the present in its eagerness for the future. In the New Testament sense of the word, ‘advent’indicates a close connection between the saving presence of Christ who has already come and the future. The hour that is coming already is now (cf. Jn 4:23; 5:25; also Mundle 1975:324). Anticipation is more about adventus (the coming of the present One) than it is about futurum. The future is not something in a far away distance, but an active force of promise and hope and resurrection in the present (cf. Moltmann [1969:177−178]). This understanding of the future as adventus clearly has profound implications for the liturgy. The present (presence of Christ) is celebrated precisely because the future is already here. It prevents us from practising a type of liturgical escapism, or an ‘apocalypticisation’ of our hope. Anticipation is not about waiting for certain(apocalyptic) events, but about participation in the future. Liturgy could indeed be called an anticipatory participation in the presence of the coming One. In the light of this understanding of adventus, it could be a fair question to ask whether the future is not strangely absent from our liturgies. Often the future is treated as a distant and totally unknown phase of time, rather than celebrated as gift that already fills the present with meaning. The latter point does not negate the fact that we have ‘not yet’ reached the telos of time. On the contrary, the liturgical act of lament, for instance, does not only take place in the light of evil because it is simply there, but because the tension between what is (the presence of the future) and the discrepancies and paradoxes calledforth by evil cries out for a ‘final’ answer and solution (i.e. the future of the presence). This tension between the future that is already with us and simultaneously not yet, finds its best expression in the Eucharist. Purcell (2001) elaborates:The present celebration of the Eucharist is referred to a past which exercises a certain judgment over the present and summons the present celebration to be responsible and faithful celebration. But, so too with the future orientation of the Eucharist. The life, death and resurrection of Christ which establishes the new covenant inaugurates the kingdom of God, and thus provides a substantial anchor for that ’pledge of future glory‘ (pignus futurae gloriae). The future is not an emptypromise; it has already been established… It already has a content which has been realized in the life, death and resurrection of Christ… Thus, as with the past, the future has a certain exteriority with regard to the present. It is that which, along with the past, gives a present. (Purcell 2001:142−143) Indeed, what are the signs of the sacraments other than representations of this eschatological tension of our faith? In the sacraments we ‘see’ the connectionsbetween our faith, our senses and our existential questions concerning the meaning of life, or put in other words: the theology and praxis of the sacraments make manifest the sensorial and supra-sensorial, as well as the existential dimensions of our faith. In the sacraments we have symbols that strongly cry out for sensory exploration and utilisation, symbols that can help us not only to celebrate creation, but also salvation and anticipation of the summation, the ultimate triumph ofGod’s beauty, goodness and truth (cf. Höhn 2003:248). Even for postmodern people, with their fundamental distrust of anything that even faintly resembles metaphysics, the Eucharist offers a meaningful, iconicexpression of the search for meaning, also in religious terms. Postmodern concepts such as ‘presence’ and ‘absence’ gain a deeper meaning in the Eucharist (cf. Mitchell 2005:143) Through the Eucharist we are incorporated into the tension of faith in the present absent God, the already and not yet that permeates our existence. But this experience of the tension of times (the already and not yet) cannot be abstracted from our experience of space. Time and space cannot, and indeedshould not, be separated.

|

Liturgy: A space for anticipation

|

|

In recent years there has been a renewed interest in the notion of ‘space’ in various sciences. Whilst spatiality was predominantly seen as a chartable reality up till the seventies, the works3 of people like Lefebvre and Soja have paved the way to understand space as ‘always becoming, in process, and unavoidably caught up in power relations’ (Hubbard, Kitchin & Valentine 2004:4, 10). Soja in particular pointed out the historical and socio-dynamical characteristics of space, that is, the factthat society simultaneously produces, and is a product of space (1996:72). It is therefore important to remember that space is also a culturally determined phenomenon, as every culture continuously forms its own concepts of space,resulting in a variety of interpretations of the notion: ‘Physical space is continuously redefined by human presence and individual interpretation of the ideology of place’ (Matthews 2003:12). For different cultures, powers and individuals ‘space’ could mean different things. The very same space could for instance be interpreted differently, even radically opposing, from the viewpoint of a farmer, a land developer, an ecologist, or a homeless person or community. The quality or potential ofa specific space is determined inter alia by the attitude, perspective and expectation of those that view it. Space is also constituted by the way in which we approach space. Although space could be chartered by geologists and chartists, it represents much more; it is also asymmetrical to charts, is also ‘neighbourhoods of, and for, imagination’

(Friedland & Hecht 2006:35). In recent sociological studies, space has been classified in terms of at least three categories, taking the cue from scholars like Soja and Lefebvre:

• ‘Firstspace’, which can be chartered and indicated geographically, e.g. physical places like Cape Town and Jerusalem

• ‘Secondspace’, which indicates imagined space (concepts, ideas on how space is or should be), in other words idealised space

• and ‘Thirdspace’, i.e. lived or existential space, which indicates the immediate, real surroundings in which people find themselves every day. ‘Thirdspace’

is often decorated aesthetically and symbolically with personal items (like furniture, paintings), or cultural expressions of communal agreements (like monuments,parks, etc; cf. Matthews 2003:12, 13).

These sociological distinctions are clearly useful, inter alia in view of our liturgical understanding of space. It could and should however also be expanded from aliturgical perspective,

in order to express more adequately the unique character of so-called ‘liturgical space’. Therefore we venture a further distinction:

• ‘Fourthspace’, which links to ‘Secondspace’ (imagined space), but also transcends it. ‘Fourthspace’ could be called anticipated space, in the sense of

ananticipatory prolepsis of transcendent realities, in such a manner that not only imagined space is viewed from a distance, but rather that the viewer already partakes in the object

of prolepsis. The transcendent reality enters the viewer’s immanent reality, but never to the degree where the transcendent reality can be grabbed and controlled; rather the viewer takes hold

of it through faith. To understand (and enter) this form of space one needs a distinctive form of spirituality, and therefore‘Fourthspace’ could also be called a spiritual space,

calling for a spirituality of anticipation.

Reflection on the phenomenon of space is of course nothing new. The Greeks for instance attributed specific meanings to space. The Greek word chora originallyindicated something like

an open space or piece of land, but was also understood by someone like Plato as a medium within which the cosmos was originally created, thus a type of space before space.

Therefore the Greeks also described chora in terms of feminine categories, for instance as womb, as giver of life, as space for nurturing and caring, a chora that triumphs over

chaos, and so effecting space for living (the Greeks also called the latter topos; cf. Flanagan 1999:15−43). Within this context chora gradually developed the ethical meaning of ‘creating or giving space to the other’. Within this gift of space the potential or ability for intellectual

and spiritual understanding is consequently born, it becomes a type of container or conduit for meaning, originating especially through discourse.Derrida calls space, probably following the Greek

meaning of chora, a ‘hermeneutical dynamics of interactive discourses’ (cf. Økland 2004:154). In this sense chora can simple mean ‘potential’, the possibility for interpretation and analyses, which in turn implies the further possibility to discover new truthsand formulate new visions. Precisely for this reason space is imaginative and anticipatory: it can envision other spaces in such a manner that these spaces are in fact called to life. Baudrillard (1994:3) calls this imagination and anticipation simulation: simulating the other, unknown space in such a manner that this simulation becomes reality. It is clear that space is a multidimensional concept, which could include all four of the aforementioned categories. In this article I propose that, although ‘liturgical space’ could and should incorporate Firstpace and thirdspace (physical and existential space), it must also be said that liturgical space intends to recreate andtranscend these forms of space to become Secondspace and Fourthspace, that is, imaginative and anticipatory space. ‘Liturgical space’ is therefore understood, in conjunction with the original Greek concept, not only as a quantitative, physical locality, but also as a primaryqualitative possibility for existence, as meaningful womb, as neighbourhood for imagination and space for anticipation. One could probably also call liturgical space an ‘atmosphere’ of imagination and anticipation, which enables one to hermeneutically transcend reality in such a manner that this reality is in fact changed, or even better: it enables one to live from and within the discovery that this reality has already been changed, irrevocably changed, through the cross and resurrectionof Christ. Such a liturgy, that represents and opens up a space for imagination and anticipation, has certain consequences. I limit myself to three, namely anticipation aswaiting, celebrating, and refiguring.

Anticipation as waiting - for whom?

In liturgy we grapple in anticipation with, and of, the Deus absconditus, the hidden and elusive God, posing our existential questions and waiting for the answers in silence. Actually, we pose only one fundamental question: ‘who is God?’ When we say ‘God’, this is a question, the most profound question of our lives: ‘who are You, O God, what is Your Name, where are You to be found?’ Miskotte (1976) wrote a moving, homiletic paragraph about this most profound question: The preacher stands there and the people are waiting for him. An awesome moment! To sink through the floor. Because he may not give a lecture, nor a speech, nor tell a story. The people lift their faces and with their silent attention, pose their question. The people say – and they are quite right: now youmust understand that this is a meeting, not of only people, but of God with us. Now you also wish to hear God speak, you yourself have created the expectation, therefore you bring our most profound question to attention, the question that elsewhere is kept strictly secret, although it always worries us: the question about God, about the living God. Woe to the preacher who should ask this one question. And also: happy is the preacher who does this, because he senses the terribleand wonderful pressure of the impossible, he feels that but one thing remains: to become an instrument, a droning and comforting organ, played by God (freely translated). (Miskotte 1976:200) This waiting upon God could also be called a hermeneutics of expectation (cf. Cilliers 2008:70). Ricoeur used the concept ‘hearkening’ [l’écoute] to refer to a pre-ethical form of obedience, before you do anything, you should listen (quoted in Snodgras 2002:29). It represents a mode of being, before it can become a mode of doing. In this process of expectant listening you are no longer in control, rather dependent on that which you receive. Ricoeur even takes a further step back: before you canlisten you should be quiet, the latter state being the source of ‘hearkening and obedience’ (quoted in Snodgras 2002:29). The memory of God’s presence fills us with hope for the future revelations of God: To be aware of divine hiddenness is to remember a presence and to yearn for its return. The presence of an absence denies its negativity… Presence perceived in an epiphanic visitation, a theophany, or the invaded solitude of a prophetic vision was ‘swift-lived’, yet the acceptance of the promise it carried transformed those who received and obeyed the command. Faded presence became a memory and a hope, but it burnt into an alloy of inward certitude, which was emunah, ‘faith’. WhenGod no longer overwhelmed the senses of perception and concealed himself behind the adversity of historical existence, those who accepted the promise were still aware of God’s nearness in the very veil of his seeming absence. For them, the center of life was a Deus absconditus atque praesens. (Terrien 1978:321, 470) In short: the God whom we are waiting for, is absent in presence and present in absence.

Anticipation as celebrating: To dance the future

This waiting on the present, absent God, should however not lead us into theological depression. The ‘killing of time’ should not kill us, but rather kindle a new energy for life, that is, a re-energiSed hope. Those who anticipate and celebrate; those who hope, dance (speaking metaphorically, not excluding the fact that those

that can, can, literally!).

Nowhere are the connections between dancing and hope expressed more movingly than in the writings of Victor Frankl (1947). On the second night that Frankl

was in Auschwitz he was woken up by the sound of a violin playing a mournful tango. He thought of someone who had to celebrate her birthday in a cellblock

only a few hundred metres from where he was. So near, and yet so far, he thought. It was his wife. In his imagination he stood up and danced with her, and in his

imaginative dancing, he filled the dark hours of the present with a hope against all hope (Frankl 1947:56−60).

Or, consider the writings of Henri Nouwen (2004), compiled after his death and entitled: Turning my Mourning into Dancing: Finding Hope in Hard Times. In this he

says:

Mourning makes us poor; it powerfully reminds us of our smallness. But it is precisely here, in that pain or poverty or awkwardness that the Dancer invites us to rise

up and take the first steps. For in our suffering, not apart from it, Jesus enters our sadness, takes us by the hand, pulls us gently up to stand, and invites us to dance.

We find the way to pray, as the psalmist did, ‘You have turned my mourning into dancing’ (Ps 30:11), because at the centre of our grief we find the grace of God.4

(Nouwen 2004:6)

There indeed seems to be a definitive relationship between hope and dance. Joan Erikson wrote the following poem only weeks before her husband’s death:

“Hope”

The word “Hope” the learned say

is derived from the shorter one “Hop”

and leads one into “Leap”.

Plato, in his turn, says that the leaping

of young creatures is the essence of play –

So be it!

To hope then, means to take a playful leap

into the future – to dare to spring from firm ground –

to play trustingly – invest energy, laughter;

And one good leap encourages another –

On then with the dance. (quoted in Capps 1995:176)

To dance is to hop in hope. It is to leap, like a young creature, into the future. To hope is to hear the melody of the future. Faith is to dance it (Alves 1972:195).

Anticipation as refiguring: An aesthetical perspective

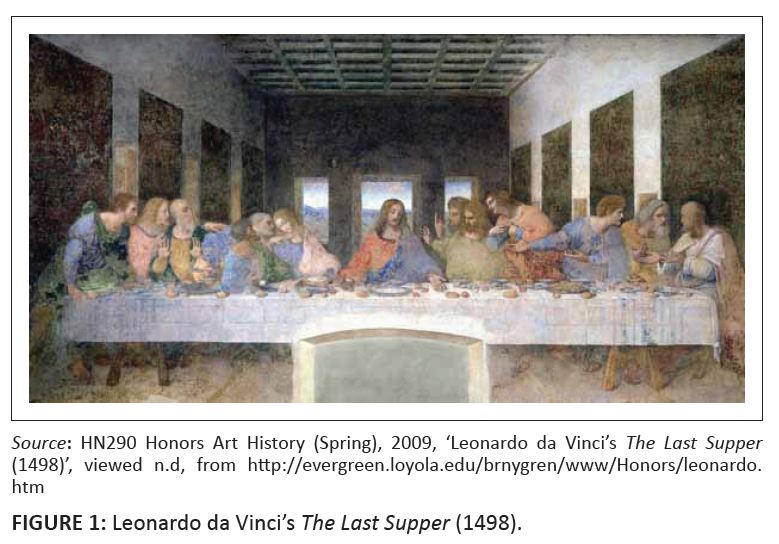

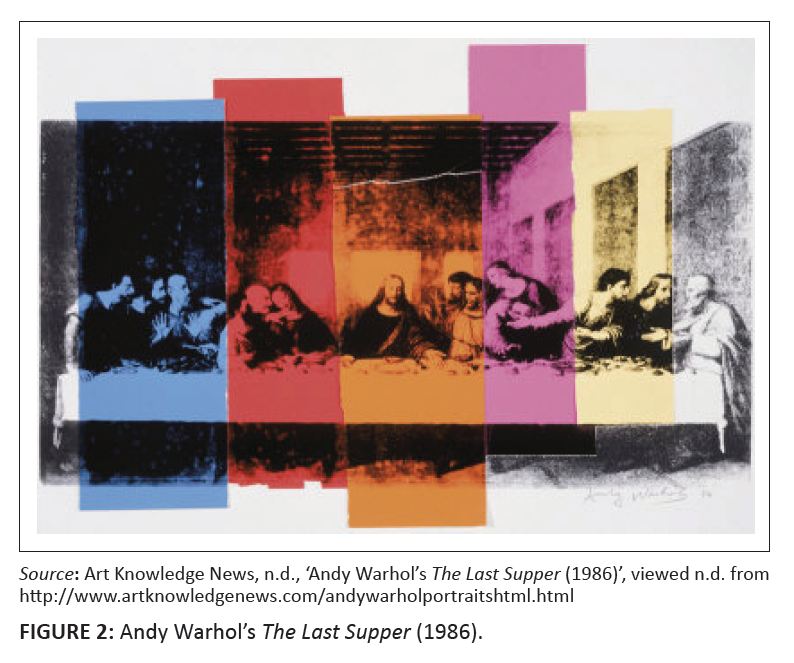

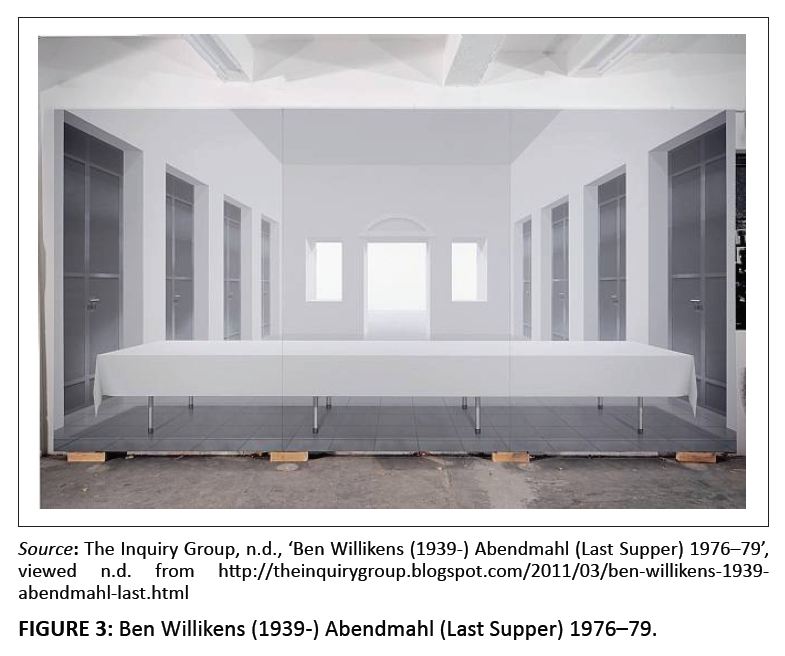

Nowhere is anticipation (hope) better expressed than in the Eucharist. The Eucharist could obviously be understood in a variety of ways. Instead of following the lines of well-known dogmatic and ecclesiological differences and nuances, I prefer to refer to three art examples in this regard. First, the classic work of Leonardo daVinci, entitled The Last Supper (completed in 1498; see Figure 1). It should be said outright that it is impossible to do justice to this work within the limitations of an article of this nature. So the scene is set: Jesus has told the disciples that one of them would betray him. He is the focal point of the whole painting: all angles and lighting point towards the vanishing point for all perspective lines, which is Jesus’ head. All twelve apostles react differently to the news, ranging between anger and shock. All the disciples face the viewer, together with Jesus, that is, they all sit on one side of the table. Judas leans back into the shadow. Jesus states that the one who will betray him willtake bread simultaneously with him. With his left hand Jesus points to a piece of bread on the table. Judas, distracted by a conversation between John and Peter, reaches for a different piece of bread, not noticing that Jesus too is stretching his right hand towards this bread. Broadly speaking, one could say that the painting is filled with a sense of serenity, but also uncertainty. Lord, am I the one? What will happen if You are betrayed? What will happen to us? One of the first recorded commentators on the mural, Luca Pacioli, wrote the following on 14 December 1498: One cannot imagine a keener attentiveness in the apostles at the sound of the voice of ineffable truth which says, ’Unus vestrum me traditurus est‘. Through their deeds and gestures, they seem to be speaking amongst themselves, one man to another and he to yet another, afflicted with keen sense of wonder. (quoted in Nicholl 2004:297) The Last Supper indeed becomes a womb for the creation of new meaning through dialogue, a chora for hermeneutical dynamics of interactive discourses. The words of Jesus about the betrayal linger in the air. They are disruptive words, creating a liminal space, a dangerous space, eating suddenly becomes a hazardous enterprise, but also a space filled with unthought-of promises and possibilities, of sharing bread with Jesus in a salvific manner. The space of the Last Supper becomes electrified with the anticipation of a multitude of possibilities. The past (the history of Jesus with these twelve men) is re-interpreted in this Eucharisticpresent; this present becomes inundated by future uncertainties and possibilities. Time and space becomes connected in a specific way, through the words of Jesus. In the process, the Last Supper becomes a prolepsis of the crucifixion, and therefore resurrection. This interpretation is not the case in Andy Warhol’s version of The Last Supper (see Figure 2). In Warhol’s painting, or rather poster, he (deliberately) makes use of a cheap black and white reproduction of the classic portrayal of The Last Supper (seen here behind the segments of added colour), but in the process falls victim to a ‘commonplace mass media motif’ (Van de Hoogen 2000:170). By emphasising the clichéd dimensions, the motif loses its original, spiritual resonance, as experienced when viewing Da Vinci’s masterpiece. In Warhol’s art, which represents the so-called American pop art revolution the: gods and goddesses were the cardboard heroes of the mass media ... Andy Warhol did more than draw on the experiences of the advertising world ... he actuallyused the techniques of mass-reproduction to create his pictures. (Muller & Bellido 1985:213) In this depiction of the Last Supper, time and space are connected (or rather disconnected) through kitsch. Or, should we say that Warhol specifically wanted to bring to our attention (in a type of anti-aesthetical manner) the degeneration of image into cliché in our society and particularly in our religion? He was obviously enough of a keen observer of culture to be able to do just that. He simply ‘held up a mirror to society and paintedwhat he saw – perhaps in the long run the most damning indictment of all?’ (Muller & Bellido 1985:213) If the aforementioned interpretation of Warhol’s poster is the case, then the added segments of colour could be interpreted as an attempt to restore some ‘life’ to the scene, exactly because cliché has eroded the spiritual meaning of the Eucharist into commonplace and unimaginative repetition. Does Warhol’s depiction not exposeour many efforts at ‘brightening up’ the liturgy and Eucharist, efforts that in fact contain no depth, but are born out of an urge for commodification? Does it express a space that is no longer a (spiritual) prolepsis, but rather a (pop) ‘re-production’? A third artwork which I wish to discuss is by the German artist Ben Willikens, entitled – what else? -The Last Supper (see Figure 3). One immediately recognises the analogy with Da Vinci’s famous painting, the setting and lines of perspective are identical. Williken’s painting could clearly also be interpreted in many ways. For some, this may in fact just represent another form of commodification of the most intimate of religious experiences. The scene could be reminiscent of the sterile space of a hospital, the Eucharist table even resembling an operation table, in which all meaning of the Eucharist is being sanitised; all spirituality stripped and sponged away. In my opinion; however, Willikens’ painting seems to be a powerful refiguring of the deepest intention and indeed spirituality of Da Vinci’s classic painting, and not commodification, like in Warhol’s work. Yes, Willikens’ Eucharist table is empty. There is no Jesus, and no disciples. And yet, somehow, the table is cleared, andthen set again for a new understanding of Eucharist. The scene is refigured; the clutter of commodification cleared away, an ‘operation’ that in my opinion is direly needed in many of our current liturgical activities. But there is an even deeper theological meaning in Williken’s painting. Because, theologically speaking, Jesus is in fact no longer here, but has ascended to heaven. Simultaneously, Jesus is in fact still here, through the coming and presence of his Spirit. The ‘empty’ table represents the era of the Spirit, and as such a space ofexpectancy; it is pregnant with possibilities; it portrays the ‘presence of absence’ in an aesthetical, and theological, compelling way. Time and space are connected by Nothing, but not nothing as in the plays of Beckett or Shakespeare, rather the Nothing of a table filled with the presence of Someone. The table waits upon the arrival not of Godot, who never comes. The table waits upon the arrival of God, who has already come.

|

FIGURE 1: Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper (1498).

|

|

|

FIGURE 2: Andy Warhol’s The Last Supper (1986).

|

|

|

FIGURE 3: Ben Willikens (1939-) Abendmahl (Last Supper) 1976–79.

|

|

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no financial or personal relationship(s) which may have inappropriately influenced him in writing this article.

Alves, R.A., 1972, Tomorrow’s Child: Imagination, Creativity, and the Rebirth of Culture, SCM Press Ltd, London.

Art Knowledge News, n.d., ‘Andy Warhol’s The Last Supper (1986)’, viewed n.d. from http://www.artknowledgenews.com/andywarholportraitshtml.html

Baudrillard, J., 1994, Simulacra and Simulation, University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, MI.

Berlin, N., 1999, ‘Traffic of our stage: Why Waiting for Godot?’, The Massachusetts Review, Autumn.

Capps, D., 1995, Agents of hope: A pastoral psychology, Fortress Press, Minneapolis, MN.

Cilliers, J.H., 2008, ‘Skrifbeskouing en Skrifhantering: perspektiewe op ‘n hermeneutiek van verwagting’, Verbum et Ecclesia 29(1), 62−76.

Cilliers, J.H., 2009, ‘Time out. Perspectives on liturgical temporality’, Nederduits Gereformeerde Teologiese Tydskrif 50 (1&2), 26−35.

Flanagan, J.W., 1999, ‘Ancient Perceptions of Space/ Perceptions of Ancient Space’, SEMEIA 87, 15−43.

Frankl, V.E., 1947, Ein Psycholog erlebt das Konzentrationslager, Zweite Auflage, Verlag für Jugend und Volk, Wien.

Friedland, R. & Hecht, R.D., 2006, The powers of place: Religion, Violence, Memory, and Place, ed. O.B. Stier & J.S. Landres, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, IN.

HN290 Honors Art History (Spring), 2009, ‘Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper (1498)’, viewed n.d, from http://evergreen.loyola.edu/brnygren/www/Honors/leonardo.htm

Höhn H.J., 2003, ‘“Zeig’s mir!” Theologie zwischen Ethik und Ästhetik’, Katechetische Blätter. Zeitschrift für Religionsunterricht, Gemeindekatechese, Kirchliche Jugendarbeit 128(4),

242−248.

Hubbard, P., Kitchin, R. & Valentine, G. (eds.), 2004, ‘Editors introduction’, in Key thinkers on space and place, pp. 1−15, Sage Publications, London.

Knowlson, J., 1996, Damned to Fame: The Life of Samuel Beckett, Bloomsbury, London.

Lefebvre, H., 1991, The production of space, Blackwell, Oxford.

Matthews, V.H., 2003, ‘Physical Space, Imagined Space, and “Lived Space” in Ancient Israel’, Biblical Theology Bulletin 33(1), 12−20.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/014610790303300103

Mitchell, N.D., 2005, ‘Mystery and Manners: Eucharist in Post-Modern Theology’, Worship 79(2), 130−151.

Moltmann, J., 1969, Geloof in de toekomst, Amboboeke, Utrecht.

Moxnes, H., 2003, Putting Jesus in His Place: A Radical Vision of Household and Kingdom, Westminster John Knox, Louisville, KY.

Muller, J.E. & Bellido, R.T., 1985, A Century of Modern Painting, 2nd rev. edn., Methuen, London.

Mundle, W., 1975, Come: The New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology, vol. 1, ed. C. Brown, The Paternoster Press, Exeter.

Nicholl, C., 2004, Leonardo da Vinci: The flights of the Mind, Allen Lane/Penguin Books, London.

Nouwen, H., 2004, Turning my Mourning into Dancing: Finding Hope in Hard Times, W. Publishing Group, Nashville, TN.

Økland, J., 2004, ‘“Men are from Mars and Women from Venus”; on the Relationship between Religion, Gender and Space’, in U. King & T. Beattie (eds.), Gender, Religion and

Diversity: Cross-cultural Perspectives, pp. 152−161, Continuum, London.

Pieters, S., 1996, ‘Dancing for Hope’, Spirituality column 12. The body. The complete HIV/Aids Resource, 18−25.

Purcell, M., 2001, ‘“This Is My Body” Which Is “For You”… Ethically Speaking’, in L. Boeve & J.C. Ries (eds.), The Presence of Transcendence: Thinking ‘Sacrament’ in a Postmodern

Age, pp. 135−152, Peeters, Leuven/Paris/Sterling, VA.

Ricoeur, P., 1995, Figuring the sacred: Religion, Narrative, and Imagination, Fortress Press, Minneapolis, MN.

Shakespeare, W., 1914, The tragedy of Macbeth: The Harvard Classics, Harvard University Press, Harvard, MA.

Snodgrass, K., 2002, ‘Reading to hear: A hermeneutics of hearing’, Horizons in Biblical Theology 24, 1−32.

Soja, E.A., 1996, Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles and other real-and-imagined places, Blackwell, Oxford.

Terrien, S., 1978, The Elusive Presence: Toward a New Biblical Theology, Harper and Row, San Francisco, CA.

The Inquiry Group, n.d., ‘Ben Willikens (1939-) Abendmahl (Last Supper) 1976–79’, viewed n.d. from

http://theinquirygroup.blogspot.com/2011/03/ben-willikens-1939-abendmahl-last.html

Van den Hoogen, T., 2000, ‘Dof zink en megalieten. Over de voorstelling van het onvoorstelbare’, in B. van Iersel, W. de Moor & P. Verdult (reds.), Onuitwisbaar aangedaan: Over

beeldende Kunst en Religie, pp. 153−171, Damon, Leende.

Van Wengen-Shute, R., 2003, ‘Time and Liturgy in George Herbert’s The Temple’, Theology, 98−107.

Wainwright, G., 1983, The Ecumenical Moment: Crisis and Opportunity for the Church, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, MI.

1.The première took place on 05 January 1953 in the Théâtre de Babylone, and it was voted ‘the most significant English language play of the 20th century’. Cf. Berlin, N., 1999, ‘Traffic of our stage: Why Waiting for Godot?’, The Massachusetts Review, Autumn.

2.This means that, although past, present and future could be understood as ‘separate’ tenses or stages of time, they are also intrinsically intertwined. In order for us to understand the present (hic et nunc; here and now), we need discernment (phronēsis). This entails inter alia the incorporation into the present both the past by way of remembrance (anamnesis), as well as the future by way of anticipation of its coming (adventus). ‘If we look closely at the present, we will see the past and the future in it’ (cf. Cilliers 2009).

3.Cf. for example, Soja, E.A., 1996, Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles and other real-and-imagined places, Blackwell, Oxford; Lefebvre, H., 1991, The production of space, Blackwell, Oxford. Also Moxnes, H., 2003, Putting Jesus in His Place: A Radical Vision of Household and Kingdom, Westminster John Knox, Louisville, KY – to name but a few.

4.One hears something similar from the minister, Stephen Pieters, who was diagnosed with HIV and AIDS: for him dancing became a metaphor for hope, for joy and life in its abundance: ‘From the time of my diagnosis, dance has been a major metaphor for my life with AIDS ... dancing has been an effective image of hope for my life with AIDS, because it symbolizes joy, exuberance, and love for life ... dancing in spite of it all is what hope is all about to me. Whether it’s watching it or doing it, dancing gives me joy, and I find I can’t feel hopeless when I’m feeling joyful ... I love the beauty of a dancer’s lines. I admire the grace and style which many dancers embody both on stage and off. I have a real weakness for accomplished dancers that know how to communicate with their whole bodies. I love their poise, their athleticism, their ability to express vibrant emotions with the whole body. I love the joy of exuberant dancing. There is nothing that can express hope and joy quite

as boundlessly as dancing ... I believe God appreciates dancing, too. The scriptures often associate dancing with joy and praise, as in Psalm 30:11: “You turned my mourning into dancing; you stripped off my sackcloth and dressed me with joy” and in Psalm 149:

3: “Let them praise God’s name with dancing”. When joy ends, the dancing stops, as in Lamentations 5:15, “Joy has left our hearts; our dancing has becoming mourning”... In what is thought to be one of the earliest written fragments of the Bible, Miriam and the women celebrate the parting of the Red Sea with singing and dancing (Ex 15:20−21). The story of David is punctuated with dancing throughout. When David kills Goliath, it is celebrated with singing and dancing (1 Sm 18:6−7). The people of ancient Israel commemorated other victories of David with dances, such as in 1 Samuel 21:11. David himself praised God with his joyful and triumphant dancing (2 Sm 6:14−16). It seems God loves dancing too. It’s very hard to confess that in spite of how important dance is to me, I really can’t dance, as hard as I’ve tried ... I’ve always been kind of awkward, stiff, and uncoordinated. I know that I’ll never be a featured dancer in a big musical as much as I’d love to. I’m just not very good at it. But that doesn’t stop me from being a dancer in my heart, and enjoying all the emotional benefits of dancing. Even when I was the sickest, and least able to dance, my soul danced. And that is perhaps when we all need that dancing spirit the most. A professional choreographer tells me, “everyone can be a dancer, at least in their heart”... Discover the dancer in your heart. Love, nurture, and encourage that dancer. There’s hope in dancing! And everyone can do it. Dancing with HIV and AIDS is a statement of faith!’ From: ‘Dancing for Hope’, Spirituality column 12. The body. The complete HIV/Aids Resource May 15, 1996:20. |