|

This article sought to respond to Wessel Stoker’s interpretation of transcendence, specifically his last type: transcendence as alterity. It explored

the possibilities of this last type as it moves beyond categories, proper names, types and norms toward a fragile openness of différance, always

from within the text. This transcendence of alterity paves a way for discussion on what is beyond being or beyond language, either horizontally or vertically,

so as to move away from dogmatic assertiveness toward a more poetic humility. This poetic humility, because of its openness (Offen-barkeit) and its

‘undogmaticness’, offers a fragile creativeness to our cultural–social–environmental encounters and praxis. Such poetics is found in

Heidegger’s work, as he interpreted humanity to dwell poetically in the house of being (language), if language speaks as the Geläut der

Stille. Yet Heidegger did not move far enough beyond names and proper names, as he named and identified the kind of poetry that would be ‘proper’

to respond to the Geläut der Stille. Derrida deconstructed Heidegger’s interpretation and exposed Heidegger’s disastrous method of

capitalising cultural-political names, moving beyond such capitalisation of ‘proper’ names toward différance and a messianic expectation

without Messiah. In this artricle, both Heidegger and Derrida’s conceptions were brought into dialogue with the types of transcendence proposed by Stoker.

This showed that Derrida’s thoughts deconstruct Heidegger’s proper poems and, in doing so, move towards openness and a continual response to

différance not with grand German-Greek poetry, but with fragile, temporary and maybe even prophetic poetry that is wounded by the continuous

expectation of the messianic still to come. As an (in)conclusion, the article explored the possibilities that such a hermeneutics of différance

can offer religion and culture in a particular local and highly divided national context of post-apartheid South Africa as a microcosm of a global world, whilst

being fully aware of the dangerous return of too many proper names and Begriffe within such an (in)conclusion.

|

The turn to language beyond the opposition

|

|

Transcendence or immanence

The turn to language, or the linguistic turn, makes traditional ontological interpretations of transcendence impossible as ‘there is nothing outside

of the text [there is no outside-text; il n’y a pas de hors-text]’ (Derrida 1997:158). What Derrida means here is that there is nothing

outside of the text that one can have access to without language, which is not also text. These thoughts are echoed in Wittgenstein’s (1961:68) statement

from the Tractatus: ‘5.6 The limits of my language mean the limits of my world’, that is, there is no beyond language. The Freudian

unconscious, which was, for some, the last vestige of a beyond, has made a turn towards language in the work of Lacan, who argues that the unconscious

is structured as language – ‘the unconscious is the discourse of the Other (with capital O)’ (Lacan 1966:143). Thus, there is no beyond language,

which is not also language and this enslavement to, in and of language could lead us into what Stoker describes as ‘radical immanence’

(Stoker 2010). Yet the turn to language is more radical than radical immanence, Stoker argues, in the sense that it is the deconstruction of the very opposition

between transcendence and immanence. It is a turn that opens the possibility to think beyond such oppositions in a Heideggerian sense of overcoming these

categories (Heidegger 2003). Heidegger argues that in the history of metaphysics, which is closely related to the history of transcendence, not only was the dif-ference (Austrag)

between Being and beings not thought, but the role of language was not thought either (Heidegger 1996). The all-important role that language plays in bringing

beings to appearance, in letting them be in their Being, was not thought. Heidegger’s radical critique of metaphysics is therefore also a critique of the

Western conceptualisation of language. In a sense, one can argue that Heidegger’s metaphysical turn (Überwindung der Metaphysik) is a linguistic

turn, in that it is a turn towards a new understanding of language, encompassing how humanity, Being and beings are of language and thus ‘God’

(transcendence) is of language. For Heidegger, it is language that opens up the metaphysical difference and thus humanity is implicated in that difference through language or through difference

in language. That means that the dif-fering in the difference, which belongs to all metaphysics, is an essentially linguistic event (Caputo 1982:158). Thus, both

the Being of beings and the humanity of humanity are linguistic events. ‘The way in which mortals, called out of the dif-ference into the dif-ference, speak

on their own part, is by responding’ (Heidegger 1971:209). For Heidegger, the dif-ference is essentially a linguistic event and thus the wounding of

metaphysics is essentially a linguistic event, albeit not in the sense that it happens in language, but that it is the happening of language

(Caputo 1982:162). The metaphysical turn is therefore a linguistic turn – not in language, but of language. Beings (things) appear in the

opening which the dif-ference creates, but this opening is cleared by language. The dif-ference bids metaphysics, science, ontology to come into thought and that

is a function of language, the speaking or calling (peal of stillness) of language. It does not only take place in language, but it is a function of

language – a response to the calling, the bidding, of the dif-ference into the dif-ference which is the pure poetic speaking of language. The structure of appearance is governed by the structure of language and thus the appearance of the world is different according to the different languages: The destiny of Being which is bestowed on each epoch is a function of the linguistic structure in which it is articulated … The dif-ference itself, as a

pre-linguistic structure, opens up the shape of appearance in a given age by addressing a call to that age, the response to which constitutes its language.

(Caputo 1982:163) Language opens up the field of presence in which we dwell (house of Being) and thus language structures and shapes the whole understanding of Being which is at work

in any given age. Language structures and shapes any sending of Being into an age in the history of metaphysics. Thus, in the history of metaphysics, the distinction between Being and beings is, itself, a bestowal of language, a gift of the historical movement of

‘Es gibt’. The ‘Es gibt’ of language gives to the thinker the following: • the sphere of openness in which the distinction between Being and beings is manifest • the historical moment (Zeit-Spiel-Raum) in which to say it • the specific language in which it comes to birth. This wounds metaphysics (transcendence) fatally and fatefully, as all epochal sendings of Being into a specific grammar of a particular time are relative to

previous and future sendings of Being and different ‘simultaneous’ sendings into different openings (places). Heidegger’s understanding fatally

wounds any metaphysical God-talk that speaks within the language that is given. In a sense, it makes God-talk (i.e. reference to an ontological transcendent) that

speaks within the grammar of any metaphysics impossible (or, at least, relative). However, Heidegger never believed this to be the end of God-talk, but the

possibility of a beginning – a beginning for a God-talk (metaphysics) that is fully aware of (awakened to) its limitations, the possibilities of which I

will come back to at a later stage. It is in this textual layer beyond the opposition between transcendence and immanence, in other words in the overcoming of the distinction, that Stoker (2010)

posits transcendence as alterity.

|

Transcendence as alterity as a function of language

|

|

Heidegger and Lacan

To understand this turn to language one first needs to move beyond the interpretation of language as a human tool used to re-present things. Language,

in Heidegger’s view, is not such a tool that humanity uses to bring things into presence, to re-present them, but rather language is the doing of

Being in humanity (in human speech). There is no beyond language because, for Heidegger (1971:197), it is not humans who speak, but language itself that

speaks, and this Lacan (1966:114) describes as being a slave to language. Lacan, strongly influenced by the work of Heidegger, argues that it is not humans

who impose an order on ‘reality’ through words, but language, by its mere functioning as it introduces a law (Braungardt 1999:11). Human speech

is thus a response to a more primordial address which issues from language itself. ‘Speaking is not man’s representation of Being; rather,

language is Being’s own way of coming to words in human speech’ (Caputo 1982:159). Or, in Lacan’s (1997) terminology, ‘The message,

our message, in all cases comes from the Other by which I understand “from the place of the Other”’. The Other, for Lacan, is the unconcious,

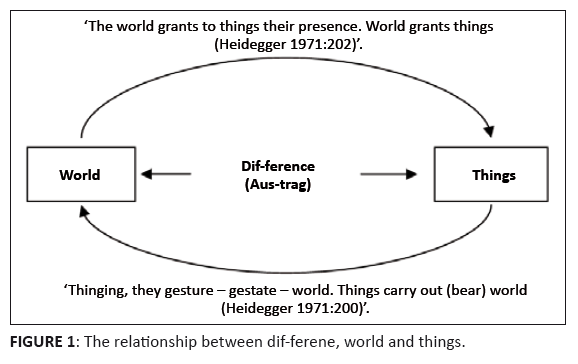

which is language. To understand the above one will need to return to Heidegger’s interpretation of dif-ference (Austrag) and how dif-ference is profoundly linguistic.

It is out of the dif-ference and into the dif-ference that ‘thinging’ things gestate world and thus world grants things their

presence1 (see Figure 1). This is an event of language that speaks as the peal of stillness (Geläut der Stille). The dif-ference is that

which calls inasmuch as it is the silent source (stillness) from which things and world emerge. It is the pure speaking of language, to which mortal speech responds.

The peal of stillness is the double stilling in that it lets things rest in the world’s favour by letting the world suffice itself in the things (Heidegger

1971:206). The dif-ference is both the bidding (call) and the place to which world and things are called. This is what Heidegger (1971: 207) means when he says:

‘Language speaks as the peal of stillness [Geläut der Stille]’.

|

FIGURE 1: The relationship between dif-ferene, world and things.

|

|

It is a silent call to which human mortal speech responds. It is the creation of a world through the gathering of things (signifiers), which, through the bidding

out of absence into presence, gestate a world via metaphor. Poems call into the realm of the absent, summoning into presence what remains absent and

therefore the poem (metaphor) does not represent things, but manifests things – it creates: poiesis. Signifiers are barred from any direct re-presentation

and only ever refer to other signifiers. This referring to other signifiers allows for the vertical unfolding of meaning, which is the poetic orientation of

language (Braungardt 1999). Words (signifiers) call into absence and bring into presence what is absent through other signifiers and this chain of signifiers

carries with it a dimension of promise or expectation, which is equivalent to desire for the other on the basis of the lack (absence) of the other. This gathering

of things – this chain of signifiers – is not enough to create meaning; a creative spark is necessary. Lacan (1966:125) argues that the creative spark

springs from metaphor where one signifier has taken the place of another. Metaphor is the substitution of signifiers (things), whereby the substituted signifier

becomes the signified element (Braungardt 1999). This substitution is equivalent to crossing the bar or barrier that separates signifier from signified, but if one

signifier is substituted for another then the substituted signifier moves below the bar as the signified and meaning is created. Thus this becomes a process of

self-authentication and, by this very principle, poetic speech is pure: the reference must be empty, no external recourse can be permitted as there is no

meta-language or an other of the other (Lacan 1977:310f). Metaphor creates world out of nothing, out of the dif-ference and in the dif-ference, and thus creates

meaning out of non-meaning and presence out of absence. One could say it creates a world ex-nihilo. We see, then, ‘that metaphor occurs at the precise

point at which sense comes out of non-sense, that is, at the frontier …’ (Lacan 1966:126−127). Or, as Lacan (1977:158) says in Ėcrits,

metaphor is the trope which ‘occurs at the precise point where meaning occurs in non-meaning’. Thus language, in its pure speaking – the peal of

stillness – is the poetry (metaphor) to which humans respond. Transcendence as alterity is thus a function of language. Alterity in the Heideggerian and Lacanian sense is interpreted as the lack or absence of the Other, it is

the non-meaning, or the abyss that one does not fall into, but it becomes a height and a groundless depth, the realm or the house of Being.2 It is this

abyss that is bridged when meaning is created out of nothing, presence out of absence, in the calling of dif-ference into dif-ference. Here, where things

gestate, world and world grants things their place, through substitution, an event of language – a function of metaphor.

|

Levinas and the radicalisation of the Other

|

|

Levinas was not content to respond to this poetic language of dif-ference with Gelassenheit, as Heidegger suggests, where one would let the

Other be Other and passively (gelassen) receive the sendings of Es gibt. The question for Levinas was not about letting the Other be other,

but how the Other fundamentally affects me (Visker 2000:248). Levinas begins, just as Heidegger and Lacan, by challenging the traditional view of language, knowledge and the concept of I think, where the

identity of the I is constructed by a reduction of the other to the same in the re-presentation of the other within the same of the I.

Levinas specifically challenged the circularity and totalising tendency of such circular ego-logical thought.3 Levinas also believed this including

of alterity into the same to be the logic of traditional views of language understood as a human tool for re-presentation: Language can be construed as internal discourse and can always be equated with the gathering of alterity into the unity of presence by the I of the

intentional I think. (Levinas 2002:78) Levinas questions this immanence or ego-logy of language by arguing that this immanence of discourse (language) is only possible because of a forgotten

sociality which is presupposed by the rupture, ‘however provisional, between self and self, for the interior dialogue still to deserve the name

dialogue’ (Levinas 2002: 79). This sociality is prior and irreducible to the im-manence of re-presentation as it is other than the knowledge that an

ego can gain of an other as a known object: Does not the interior dialogue presuppose, beyond the representation of the other, a relationship to the other person as other, and not initially a

relationship to the other already apperceived as the same through a reason that is universal from the start? (Levinas 2002:79) Levinas argues that thought, knowledge, language are summoned – or invented – not in and of dif-ference, but on the basis of certain exigencies

that depend on the ethical significance of the other, inscribed on his or her face (Levinas 2002:80). Levinas thus radicalises the absolute alterity of

Heidegger’s dif-ference by recognising this opening of dif-ference that summons and into which the summoned arrives (the event of language) in the face

of the other. The difference or otherness of the other is not to be thought of in terms of certain parts of a whole that are marked off in opposition to one another, where

this one is different to that one. Levinas argues that the alterity of the other is more primary than such a difference between parts, as the face of the other

obligates the I, which, from the first – without deliberation – is responsive to the other. ‘From the first: that is, the self

answers “gratuitously,” without worrying about reciprocity’ (Levinas 2002:78). It is the concrete other, the neighbour, or, more importantly,

the widow, orphan and stranger, that radicalises this alterity that moves us from Gelassenheit4 towards ethics and justice. It is no more just a matter of

receiving the different sendings of Being and the relativity of the different sendings in Gelassenheit, but it is a radical call into ethical responsibility

towards the other who summons me. It is the face and the facing of the other, which cannot be contained and which escapes sameness and thereby questions sameness as the self, which places

the self in an inescapable responsibility towards the other. It is in and through the face of the other that the self is held hostage in an infinite

responsibility, as Lacan would say – a slave to the other, but, for Levinas, not the abstract Other of the unconscious or the abstract Other of

dif-ference, but the concrete other of the neighbour who demands: Thou shall not kill! Thou shall not let me die! Thou shall not assimilate me into the

same and thereby kill my otherness!5 This otherness is inescapable and it knocks on the door of every metaphor that creates world ex-nihilo where beings (things) have their place. It is

an otherness that disturbs and disrupts all signifying chains of metonymy as it is the stranger, the other other which is not included as one of the

‘things’ gathered, that through metaphoric substitution creates world and then world grants privileged place to the things. It is the other who seeks

asylum in that created world, it is the orphan and the widow of that world seeking welcome by seeking hospitality, a place, amongst the citizens (things) of that

world, but who – in seeking place in that world – challenge the gestating of the world, challenge the metaphor, disrupt the metaphor. The host

(creation through metaphor) becomes the hostage of the other seeking hospitality, seeking a place in that world. The other challenges the unity and the order of the

poetic world by seeking place, but in seeking place the world is challenged. The dif-ference calls and thus bids one to name, to create ex-nihilo, but every

response, every creation is not enough, is not final, as it does not silence the bidding; the bidding is infinite, the debt of responsibility cannot be paid and the

bidding continues unabatedly.6 This would leave the self with an infinite responsibility that cannot be met, which would leave the self before an abyss,

were it not for the third person and human plurality. It is in the presence of the third person that the self is obligated to compare unique and incomparable others: this is the moment of knowledge and, henceforth, of an objectivity beyond or on the hither side of the nakedness of the face; this is the moment of consciousness

and intentionality. An objectivity born of justice and founded on justice, and thus required by the for-the-other, which, in the alterity of the face,

commands the I. (Levinas 2002:81) It is this call for justice in the presence of the third that is also a call for re-presentation that ceaselessly covers over the nakedness of the face and

that thus gives it content and composure in the world. But this objectivity and re-presentation can never forget the primary call and summoning of the other and

is thus always wounded. For Heidegger, transcendence as alterity was the opening, the event of language – dif-ference. For Levinas, transcendence as alterity is not so much this

opening, but time (Caputo 2007:190). The time of the other who disrupts the language of the same, the language of re-presentation. Not time as in the movement

between the different modalities of time, namely past to present to future, but an interruption of time by answering a call that one has never heard (pure past)

(Levinas 2002:83−85) and answering a call one cannot foresee (pure future) (Levinas 2002:85−86). The other summons the self even before the self is

aware of itself and thus summons the self from an immemorial past. This summons cannot be answered adequately and thus the summons cannot be foreseen or foreclosed.

|

Derrida and transcendence as alterity

|

|

There are certain similarities between Derrida’s understanding of différance and Heidegger’s dif-ference, as Derrida himself acknowledges

in ’The end of the book and the beginning of writing’.7 Derrida uses the term ‘différance’ in addition to the

term ‘trace’ to speak of the infinite chain of signifiers signifying each other, which always creates both a difference and a deferment of meaning.

In Derrida’s interpretation of language, language seeks to transcend itself as it explores its own limits, seeking to reach that u-topia (no-place) beyond

language in language – a mystery place that does not exist. It seeks to reach the place of the unthought that gives to thought – the event of language,

or the event of thought which is very similar to Heidegger’s dif-ference. It is a beyond in and of language. If one wants to talk of God, this could be the name given to such a non-place that constantly erases itself, that gives to thought, but cannot be thought

itself. ’”God” “is” the name of that bottomless submerging, of the endless desertification of language’ (Derrida 1998:59).

For Derrida, the passion for the ‘beyond’ takes the form of the passion for the place, the impossible place, but which is also a passion for

existence.8 One could say that it is a passion for a non-place or a passion for an impossible place – u-topia, but with this passion Derrida

does not return to an ontological place beyond or a transcendent place, but remains within Levinas’s idea of transcendence as time: The passion for the impossible is for something that breaks up and breaks into the world that otherwise tends constantly to settle in place all around us; it

means something that extends us, that draws us out of ourselves beyond ourselves. This would also be the passion of existence – the spark that drives

existence past itself and ignites a certain self-transforming. (Caputo 2007:190) This is what time does, as it is the event of alterity. Lives are pried open by the coming of the other, ‘by something “coming” to us from beyond

the horizon of foresee-ability, something that destabilizes us even as it constitutes us as wounded or destabilized, as cut or circum-cut subjects’ (Caputo

2007:190). It is for this reason that one can speak of a messianism without messiah or a religion without religion. It is the coming of the unknown, the one that

cannot be capitalised, who does not have a proper name. It is the coming of the nameless, the unthought, one who or what breaks open the thought (language) of the

given so as to make room (offer hospitality) for the other. This is a passion for justice by offering the unthought (other) hospitality. It is a passion for democracy

by offering the unheard other voice a chance to speak and to be heard in the given. Both these passions (justice and democracy) are passions not for a place, but are

the passions for u-topia of a non-place which is absolutely other, but, being an absolute other and therefore an impossible other, this passion disrupts the present

(what is present or given in the present moment) with what is to come – the coming of the other. All texts, thought (metaphor), any world as a creation ex-nihilo, has holes in it, namely the holes or gaps of the unthought other. It is the task of thinking

to think the unthought (Heidegger 1962:207), that is, to think the difference and the deferment of thought and the unthought and this is the basis of

Dekonstruktion or deconstruction. In Levinas’s terms, it is to think the other, the neighbour and, more importantly, to think the widow, orphan and

stranger, and if one adds the second element of Derrida’s (1982) différance, namely deferment, it would mean to think the not yet born,9

who all seek a welcome – hospitality.

|

Ricoeur’s transcendence as alterity within the text and a poetic hermeneutic

|

|

From Heidegger and Derrida one learns that there is no beyond language or text and that language is purely poetic (Heidegger) or metaphoric (Derrida10).

This linguistic turn certainly makes it impossible to speak of a metaphysical onto-theologically existing God outside of language and, in that sense, this linguistic

turn is the death of the metaphysical God. Yet, it does not prevent one of speaking of the God of the text and, more specifically, of the God of the sacred text

– not that one wants to make too strong a separation between sacred and mundane texts, for all texts contain alterity that has the creative potential

to create worlds before the text.11 Ricoeur understands this potential as a capability inherent in both texts and humans (Meylahn 2005:124). This

concurs with Derrida’s understanding of metaphor, in that this ability is that which is proper to humanity.12 There is no beyond metaphor,

as even the beyond will be metaphor (Derrida 1974). Yet, one can argue that in most language games this metaphoric event of language has been forgotten. Within

religious language or mythological language, the metaphorical character of language is not forgotten,13 but, in a sense, as Jüngel (1989:32)

explicitly argues, it is religious language which challenges what is as the ultimate reference, thereby challenging what is with what is Other and, in doing

so, it employs metaphor which does not refer to the world as it is, but as it should or could be. For Ricoeur (1995:230), theology develops from this linguistic

matrix of metaphor and limit-expression and this, in turn, characterises the originary poetic language of faith. This alterity within texts allows for openness towards interpretation and thus a non-foundationalist approach to hermeneutics. Ricoeur refers to the

‘surplus meaning’ that exists in texts that is bound up with the inexhaustibility and arbitrariness of language as discovered above. Every word

is ‘multiply located, possessing multiple significations and references, associations and implications’ (Ross 1994:22). This surplus meaning

(alterity – that which is other or beyond the given meaning) is what questions the given meaning. It is this surplus meaning that challenges the given and

opens up the possibility of other interpretations by continuously creating an alternative world before the text. Thus hermeneutics is not just interpreting texts, but it is about producing meaning from the semantic surplus of a text. Does this mean that all interpretations

(i.e. productions of meaning from the semantic surplus) are equal and relative to each other? Ricoeur (1981) offers a two-pronged approach to circumvent this

relativism in hermeneutics – a subjective approach and an objective approach. For Ricoeur (1976:92), the subjective approach is not to try and discover the

intentions of the original author or the interpretations of the original readers, but ‘what has to be appropriated is the meaning of the text itself,

conceived in a dynamic way as the direction of thought opened up by the text’. Ricoeur (1991:169) insists that imagination is the linguistic potential that

works within and through the speaking of language (metaphor) to create and discover new possibilities of meaning and existence. This is more than the traditional

understanding of imagination that is understood as conjuring up images of past or absent objects. He interprets imagination as semantic in nature, working in and

through linguistic tropes and texts to create and discover new possibilities of meaning and existence (Ricoeur 1978:148). This is an event in texts as semantic

imagination exploits the polysemy of words and the plurivocity of texts (i.e. the alterity of texts), in order to call into question (and deconstruct) the status

quo and to project new, different worlds as possible ways of restructuring reality (Putt 2004:962). Yet one needs to be critical of one’s own ideology and

thus one needs to undergo a self-interpretation, whereby the reader becomes aware of the lenses that he or she uses to read the texts. Ricoeur’s second approach (1980:101) – the objective approach – is to discern the labour of the text itself. It is not a free imagination, but

the imagination is determined by the effects of the text itself. Jüngel, according to Fides, was critical of Ricoeur’s approaches and argued that, in both approaches, the possible is subordinated to the actual of the

text. In this sense, the possible is always understood as the not yet of the ‘actual’ (text) (Fiddes 2000:39). For Jüngel, it was important to think

of the possible not in terms of what is possible in the actual (text), but to think of the possible in terms of what God can create. ‘That which God makes

possible in his free love has ontological priority over that which he makes actual through our acts’ (Jüngel 1989:103). Thus one can speak rather of the

impossible possible that is truly other in the text and that is, and always is, a creation ex-nihilo (i.e. a creation out of absence or out of non-meaning).

It is not only religious and mythological metaphors that have this potential, but all metaphors, and thus all language, as was discussed above. Language therefore

projects a world in front of it as part of a continuing process, because of the unsaid within language, the unthought, the other and thus one can speak of an

a-religious revelation (Fiddes 2000:40) within metaphor (language). If one imaginatively combines the different thoughts of dif-ference and différance of the Other14 (alterity), one can argue that it is

an experience of heteronomy or a heteronymous experience, as Levinas (1986:348) would say, in the text (language). Levinas (1986:348) argues that this experience

is not a contradiction but that it points to a movement of transcendence reaching us ‘like a bridgehead “of the other shore”’ and without

which ‘the simple coexistence of philosophy and religion in souls and even civilizations is but an inadmissible weakness of the mind’. It is here in

the text that philosophy or hermeneutics and religion coexist and need to be thought, which thus brings the article into the province of theopoetics and the talk

of God not beyond the text, but the God of the text – the creative Alterity within the functioning of language: transcendence as alterity within the text.

In a sense, one can speak of an incarnate God, a God who has pitched God’s tent in the house of Being. Transcendence as alterity within text can speak of a

God who, through covenant, has bound God-self to the Zeit-Spiel-Raum of human history. This is a God whose kingdom or realm is not to be found in any beyond,

but it is here as an alternative or alterity. Simon Critchley (2004:xx) argues that ‘after the death of God, it is in and as literature [text] that the issue of life’s possible redemption is

played out’. In other words, it is in the text (i.e. the literary text) that God and salvation is to be found, not an ontological God beyond the text, but in

the name of God in the text, as Caputo argues, that after the death of God we can be nourished anew by the name of God (Kosky 2008:1024). Charles Winquists (1986:49)

insists that theology is writing and, as such, it addresses the knowledge of God by engaging language about God, which, in turn, demands interpretation. How does one

write about God? How does one ‘do’ theology?

|

Theopoetics or theopoetry

|

|

In a short story ‘On angels’, Donald Barthelme (1969:29) wrote: ‘The death of God left angels in a strange position.’ David

Miller (2010:6) argues that theologians or theology currently finds itself in a similar state. Transcendence is interpreted as the experience of alterity

within the text – this leads one to the speaking of language which, according to Heidegger, is poetry and, in a sense, theopoetics. Miller (2010) defines

theopoetics as theological and/or religious thinkers who, in some way or other, are in relation to the ‘death of God’ and, I would add, the death of

God via the linguistic turn of the overcoming of metaphysics. There are different forms of theopoetics, but, according to McCullough (2008), there is something that these thoughts have in common. The thinkers may be viewed as: apologists for the vocation of straying towards an infinite nothing, or erring ‘after God,’ or waiting for the Messiah who never comes, or loving

one’s neighbour in the void as the only alternative to the bad faith of arbitrarily declared absolutes. (McCullough 2008:108) In other words, they have come to terms that there is no beyond language and that which is ‘beyond’ or other is already ‘present’ in the

event of language – the peal of stillness that summons human speech as metaphor. Miller (2010) makes the distinction between theopoetry and theopoetics to try and understand how one writes about God – how one engages in theology.

Theopoetics for Miller is theology and he thinks that if ‘after the death of God’ signifies the continuing impact of an understanding of the times as

severed from any dependencies on transcendental referents, then theopoetics will have to refer to strategies of human signification in the absence of fixed and

ultimate meanings accessible to knowledge or faith’ (Miller 2010:8). It is a poetics conscious of its metaphorical character and thus conscious of its limits.

He continues by saying it ‘involves a reflection on poiesis’ (Miller 2010:8) – the creation ex-nihilo or bringing forth out of the

dif-ference into the dif-ference. Theopoetry, in contrast, is a beautiful way of expressing theology’s eternal truths and thus theology does not end with the death of God, because there is

no death of God in theopoetry, but a creative transformation towards an: artful, imaginative, creative, beautiful, and rhetorically compelling manner of speaking and thinking concerning a theological knowledge that is and always has been

in our possession and a part of our faith. (Miller 2010:8) Theopoetics consciously engages the bringing forth out of nothing, whilst theopoetry fills the opening of the event of language with content – eternal

truths – thereby denying the creation ex-nihilo. Theopoetics, on the other hand, faces the radical crisis of faith and therefore requires a radicalised

poetics to face the nothingness, the void, the absolute alterity.

|

Theopoetry and the danger of theopolitics

|

|

This filling of the void with absolute, beautifully crafted truths is dangerous and world history has seen some great epochal sendings of theopoetry or

onto-theological poetry. There have been so many meanings projected upon us over the years – political, social, religious and ideological meanings.

Amazing empires, worlds, cultures and languages have been created in the summoning of the dif-ference and into the dif-ference, but forgetting the dif-ference.

Forgetting the void, the opening of the event of language, forgetting that there is no beyond metaphor. One only needs to think of the great cultures of the world

that have given so much to history. Es gibt has given to history great imperial metaphors that encompassed large expanses of thought, land and people. These

metaphors continued to expand so as to include large expanses of the unknown within the same. There are powerful metaphors that are not easily challenged because

they have given too many things (beings) a fixed place. We only need to think of the current Gestell of science and technology, as Heidegger would call it

– the current sending of Es gibt as the technological world and its machination that incorporates everything in its positive faith in science, technology

and capitalism. How does poetics differ from these grand poems of meaning that so easily become theopolitics? Mark Hederman (1985), reflecting on the so-called Fifth Province in Ireland, a province that does not exist except in the imagination of poets as the heart of

Ireland, one could say is a u-topia as it is a non-place, it is a non-existent place and yet it is the place that gives birth to all places as it erases

itself.15 The danger is that such u-topias can easily be filled with content and not erase themselves, but establish themselves as they become ideological

in the political sense or idolatry in the religious sense (cf. Hederman 1985). Is this not what happened to Heidegger’s poetry as it became filled with too much

geographical and ideological content? It became filled with capitalised German-Greek poems and thus was no longer a non-place, but a very specific place – a

place that one is prepared to die for and go to war for. The void was filled with the beautiful Greek-German theopoetry that too easily translated into a theopolitics

of German nationalism. The question of how to keep this u-topia free from idolatry and ideology is the challenge of theopoetics. Miller (2010:11−18) describes four makers of

radicalised poetics that respond to the void and nothingness left by the death of God and that prevent theopoetics from becoming theopoetry – a small step

from theopolitics – by filling the void with proper capitalised names.

No author

Roland Barthes (2002) wrote in his 1968 essay, ‘Death of the author’, that the author’s intentions are not and cannot be known. It is difficult

to know with finality the true source of signification in a poem or any text, because the signification itself is finally unknown and unknowable. As Heidegger argued,

as mentioned above, it is language that speaks and not mortal humanity; mortal humanity only responds to the speaking of language. Richards (1963) said something very

similar when he wrote: the great writer seldom regards him [or her] self as a personality with something to say; his [or her] mind is simply a place where something happens to words ...

Whatever the author may think that he or she is entitled to do to a poem, the poem has the last word. (Richards 1963:169) Poetry leads not only to the death of the subject, but more importantly to the death of the ego, believing that he or she has something universal to say. In

Levinas’s thought, it would be the other that speaks and our speaking is only a response to the other. This links up with the next marker of theopoetics.

No meaning

Meaning cannot be reduced to a single fixed meaning, as it is always multiple and heterogonous. There is always a différance as meaning is not

only different, but also deferred as something still to come. This concept of the multiplicity of meaning is echoed through the thoughts of Heidegger, Levinas,

Derrida and Ricoeur and it is this deferment of meaning that opens the text to Offen-barkeit, namely to reveal, manifest and create worlds before it. Poetics,

in response to transcendence as alterity, is poetic thinking that is fully awakened to the absolute alterity and responds in fragile humbleness to this alterity,

knowing full well that no poetic thought, no metaphor, will ever grasp (Begreifen) the Other in the same of proper names and thus it is playful dance in the

wounded place (Zeit-Spiel-Raum) of the event of language haunted by dif-ference (différance) or alterity.

No order

There is no order, but always complexity, for there is always a difference and a deferment and thus, although one can at times identify order, there is also

always that which interrupts and disrupts the order (the coming of the other), that destabilises and disrupts order. Miller (2010) compares this with complexity

theory, where there is both order and complex order, as in the constitution of a snowflake, and then that which absolutely defies order, namely chaos, and these

need to be thought together in complexity theory. Order, the same, is not absolute as it is always interrupted by alterity. It is always transcended by alterity and

thus opens the order for the event of the other. Poetic thought does not seek to impose order, but plays in that liminal space between order and chaos of the event of

the other – that which disrupts and questions order. It plays in the Zeit-Spiel-Raum of order in the hope and in the constant prayer to and for the other

and thereby offering hospitality to the Other.

No end (enjambment)

Miller (2010) refers to enjambment, which is the breaking of a syntactic unit at the end of the line or between verses, thus creating an expectant openness to

each line and leaving the line or the poem without ending. This open-endedness creates expectancy for the coming of the other, what Derrida describes as a

messianism without messiah, a messianism without fulfilment. Theologically one could speak of deferred eschatology which creates the time that remains, which

is a time of grace where judgement and finality are deferred. It keeps the door open and offers a welcome to the Other with a radical openness, Offen-barkeit,

to what is to come without author, meaning, order or finality.

The theopoetics between theopoetry and theopolitics

The global politics of the last few decades has manifested the danger of theopolitics that arises so easily out of theopoetry. The rise of fundamentalism on

all sides, the traditional religious fundamentalism (Islam, Judaism and Christianity), but also empirical-scientific and rationalist fundamentalism, are part of

the same sending, as Heidegger would probably say. Indeed, Žižek (1997) would argue that this manifestation of fundamentalism is the logical outworking

of global capitalism, for global capitalism is a new universalism or globalism that has forgotten its metaphoricalness – the speaking of language. South Africa is a country faced with so many socio-economic and political challenges and thus there are many who seek to speak a strong word that would

provide clear coordinates to steer the country out of the stormy waters. The desire for certain knowledge, the desire for the Other, can falsely be fulfilled,

with theopoetry becoming absolute knowledge (fundamentalism) and absolute knowledge becoming the imperial politics of an unquestionable language that has forgotten

the primary speaking of language – the summoning of the other. The natural response to such imperialism is with counter-imperialism – to challenge the

absolute good (knowledge of the Other) of the one with one’s own good (knowledge of the other) and consequently demonising the other’s good. Is this

the answer to the death of God – a battle of the goods (gods)? Is the alternative to the battle of the gods a passive Gelassenheit? Is there an ethical

alternative in theopoetics? For Derrida, Levinas and Ricoeur, the battle is not a battle about what lies beyond language, but it is a battle within the text as

transcendence, as alterity, is within the text. It is not about the other outside the text, but the difference or différance within the text. The

unknown Other is not beyond the text, but in the text. Therefore the desire is not for the unknown beyond the text, but for the unknown in the text and thus

theopoetics, which takes transcendence as alterity within the text seriously, does indeed offer an ethical alternative to the battle of the gods or Gelasseneheit.

The ethical alternative is a passive auto-deconstruction combined with an active hope for the unknown and/or unthought and/or other still to come. This passive

auto-deconstruction as a function of différance brings with it a vulnerable in-conclusivity (continuous auto-deconstruction) and an active expectant

openness (Offen-barkeit) in the theopoetics (without author, meaning, order or finality) of the unknown, unthought and impossible other always still to come.

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no financial or personal relationship(s) which may have inappropriately influenced him in writing this article.

Barthelme, D., 1969, ‘On angels’, The New Yorker 45, 09 August, p. 29.Barthes, R., 2002, ‘Death of the author’, in G. Stygall (ed.), Academic discourse: Readings for argument and analysis, pp.

101−106, Thomson Learning Custom Publishing, London. Braungardt, J., 1999, ‘Theology after Lacan? A psychoanalytic approach to theological discourse’, Other Voices: The (e)Journal of Cultural

Criticism 1(3), 1−29. Caputo, J.D., 1982, Heidegger and Aquinas: An essay on overcoming metaphysics, Fordham University Press, New York, NY. Caputo, J.D., 2007, ‘Temporal transcendence: The very idea of à venir in Derrida’, in J.D. Caputo & M.J. Scanlon (eds.),

Transcendence and beyond: A postmodern inquiry, pp. 188−203, Indiana University Press, Indianapolis, IN. Critchley, S., 2004, Very little ... Almost nothing, Routledge, New York, NY. Derrida, J., 1974, ‘White mythology: Metaphor in the text of philosophy’, Literary History 6(1), 5−74.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/468341 Derrida, J., 1978, Writing and difference, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL. Derrida, J., 1982, Margins of philosophy, transl. A. Bass, Harvester Press, Brighton. Derrida, J., 1993, ‘Khōra’, in J. Derrida & T. du toit (eds.), On the name, pp. 89−127, Stanford University Press, Palo

Alto, CA. Derrida, J., 1995, On the name, ed. T. du Toit, Stanford University Press, Palo Alto, CA. Derrida, J., 1997, Of grammatology, transl. G.C. Spivak, John Hopkins, Baltimore, MD. Derrida, J., 1998, ‘God’: Anonymus, transl. R. Sneller, Agora, Baarn. Derrida, J., 2005, ‘The end of the book and the beginning of writing’, in J. Medina & D. Wood (eds.), pp. 207−225, Truth:

Engagements across philosophical traditions, Blackwell Publishers, Oxford. Fiddes, P.S., 2000, ‘Story and possibility: Reflections on the last Scenes of the Fourth Gospel and Shakespeare’s “The Tempest”’,

in G. Sauter & J. Barton (eds.), Revelation and story, narrative theology and the centrality of story, pp. 29−52, Ashgate, Burlington. Hederman, M.P., 1985, ‘Poetry and the fifth province’, The Crane Bag: Contemporary Culture Debate 9(1), 110−119. Heidegger, M., 1962, Kant and the problem of metaphysics, transl. J.S. Churchill, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, IN. Heidegger, M., 1968, What is called thinking?, transl. J.G. Gray, Harper, New York, NY. Heidegger, M., 1971, ‘Language’, in Poetry, language, thought, pp. 189−210, transl. A. Hofstadter, Harper & Row, New York, NY. Heidegger, M., 1996, Being and time: A translation of Sein und Zeit, transl. J. Stambaugh, State University of New York Press, New York, NY. Heidegger, M., 2003, ‘Overcoming metaphysics’, in Martin Heidegger: The end of philosophy, transl. J. Stambaugh, pp.

84−110, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL. Jüngel, E., 1989, Eberhard Jüngel: Theological essays, transl. J.B. Webster, T&T Clark, Edinburgh. Kosky, J.L., 2008, ‘Review of “After the death of God” by John D. Caputo and Gianni Vattimo’, ed. J.W. Robbins, Journal of the

American Academy of Religion 76(4), 1021−1025. Lacan, J., 1966, ‘The Insistence of the letter in the unconscious’, Yale French Studies, Strucutralism (36/37), 112−147. Lacan, J., 1977, Ėcrits: A selection, Norton, New York, NY. Lacan, J., 1997, Of structure as the inmixing of an Otherness prerequisite to any subject whatever, viewed 10 May 2010, from

http://www.lacan.com/hotel.htm Levinas E., 1986, ‘Trace of the Other’, in M.C. Taylor (ed.), Deconstruction in context, transl. A. Lingis, pp. 345−359,

University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL. Levinas, E., 2002, ‘Diachrony and representation’, in J.D. Caupto (ed.), The religious, pp. 76−88, Blackwell Publishers, Oxford. McCullough, L., 2008, ‘Death of God reprise: Altizer, Taylor, Vattimo, Caputo, Vahanian’, Journal for Cultural and Religious Theory 9(3),

97−109. Meylahn, E.P., 2005, ‘’n Narratief-Kritiese Benadering as Hermeneutiese Raamwerk vir ‘n Vergelykende Studie Tussen die Boeke Openbaring en

The Lord of the Rings’, ongepubliseerde PhD proefskrif, Department of New Testament Studies, Universiteit van Pretoria. Miller, D.L., 2010, ‘Theopoetry or Theopoetics’, Crosscurrents (March), 6−23.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-3881.2010.00103.x Putt, K.B., 2004, ‘Imagination, kenosis, and repetition: Richard Kearney’s Theopoetics of the possible God’, Revista Portuguesa de Filosofia

60(4), 953−983. Richards, I.A., 1963, ‘How does a poem know when it is finished?’, in D. Lerner (ed.), Parts and wholes, p. 169, Free Press of Glencoe,

New York, NY. Ricoeur, P., 1976, Interpretation theory: Discourse & the surplus meaning, Texas Christian University Press, Fort Worth, TX. Ricoeur, P., 1978, The philosophy of Paul Ricoeur: An anthology of his work, eds. C.E. Regan & D. Stewart, Beacon Press, Boston, MA. Ricoeur, P., 1980, ‘Toward a hermeneutic of the idea of Revelation’, in L. Mudge (ed.), Essays on biblical interpretation, pp. 47–77,

Fortress Press, Philadelphia, PA. Ricoeur, P.,1981, ‘What is a text? Explanation and understanding’, in J.B. Thompson (ed.), Hermeneutics and the Human Sciences, pp.

145−164, Cambridge University Press, New York, NY. Ricoeur, P., 1991, From text to action: Essays in hermeneutics, II, transl. K. Blamey & J.B. Thompson, Northwestern University Press,

Evanston, IL. Ricoeur, P., 1995, Figuring the sacred: Religion, narrative, and imagination, ed. D. Pellauer, transl. M.I. Wallace, Fortress Press, Minneapolis, MN. Ross, S.D., 1994, The limits of language, Fordham University Press, New York, NY. Stoker, W., 2010, ‘Culture and transcendence: Shifting religion and spirituality in philosophy, theology, art and politics’, paper presented at the

Culture and Transcendence Conference, Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam, 28−29 October. Visker, R., 2000, ‘The price of being dispossessed: Levinas’s God and Freud’s trauma’, in J. Bloechl (ed.), The face of the Other &

the trace of God: Essays on the philosophy of Immanuel Levinas, pp. 243−275, Fordham University Press, New York, NY. Winquist, C., 1986, Ephiphanies of darkness: Deconstruction in theology, Fortress Press, Philadelphia, PA. Wittgenstein, L., 1961, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, Routledge, London. Žižek, S., 1997, ‘Multiculturalism, or, the cultural logic of multinational capitalism’, New Left Review I(225), 34−51.

1.Heidegger (1971:206) says: ‘The dif-ference let the thinging of the thing rest in the worlding of the world.’2.Heidegger (1971:191) refers to language itself as the abyss, the groundless ground. He argues that this abyss, groundless ground, creates a loftiness and a

groundless depth which is a space or a realm, a home which is the dwelling place of humanity. ‘To reflect on language means to reach the speaking of

language in such a way that this speaking takes place as that which grants an abode for the being of mortals’ (Heidegger 1971:192). 3.Traditionally, ‘all alterity which is brought together, received, and synchronized in presence within the I think, and which then is taken up

in the identity of the I – it is a matter of understanding this alterity that has been taken by the thought of the identical as one’s own

and, in so doing, of reducing one’s other to the same. The other becomes the I’s very own in knowledge, which secures the marvel of

immanence. Intentionality, in the aiming at and thematizing of being – that is, in presence – is a return to self as much as an issuing from self’

(Levinas 2002:77).

4.‘... calling into question that restful identity – there arises, awakened by the silent and imperative language spoken by the face of the other (though

it does not have the coercive power of the visible), the solicitude of a responsibility I do not have to make up my mind to take on, no more than I have to identify

my own identity’ (Levinas 2002:83). 5.‘Face of the other – underlying all the particular forms of expression in which he or she, already right “in character,”

plays a role – is no less pure expression, extradition with neither defence nor cover, precisely the extreme rectitude of a facing,

which in this nakedness is an exposure unto death: nakedness, destitution, passivity, and pure vulnerability. Face as the very mortality of the other

human being’ (Levinas 2002:81, see also 2002:82). 6.‘The risk of occupying – from the moment of the Da of my Dasein – the place of an other and thus, on the concrete level,

of exiling him, of condemning him to a miserable condition in some “third” or “fourth” world, of bringing him death’ (Levinas 2002:83). 7.‘To come to recognize, not within but on the horizon of the Heideggerian paths, and yet in them, that the sense of being is not a transcendental or

trans-epochal signified (even if it was always dissimulated within the epoch) but already, in a truly unheard of sense, a determined signifying trace,

as to affirm that within the decisive concept of ontico-ontological difference, all is not to be thought at one go; entity and being, ontic and ontological,

“ontico-ontological”, are, in an original style, derivative with regard to difference; and with respect to what I shall later call différance,

an economic concept designating the production of differing/deferring’ (Derrida 2005:221).

8.See Derrida (1995:59).9.With reference to the unborn I am purely referring to the future and what is still to come and not hinting at the moral debates concerning abortion or gene-technology. 10.See Derrida (1974).

11.Through various creative genres of literature (wisdom, prophecy, hymn, parable, as well as eschatological sayings) one encounters a ‘call, into the heart

of the existence, of the imagination of the possible’. This summoning of revelation manifests the ‘grace of imagination’ as the revelation of new

possibilities, unknown, impossible possibilities in the gifts of freedom, hope and a redemption through imagination (Ricoeur 1978:237). 12.‘Our present position, then, is that metaphor is what is proper to man. And more properly to each individual man, according to the dominance of

nature’s gift in him. But what of this dominance? And what is the meaning here of “what is proper to man”, in connection with such a capacity?’

(Derrida 1974:47). 13.Within the text of religious mythological language the role of metaphor is not forgotten, but this does not exclude the fact that those who interpret these texts

might have forgotten the metaphorical character of the text and interpret it literally. 14.I am not arguing that these words can be equated with each other, thereby integrating them into the same and totally ignoring what is different, but simply that

there are enough similarities between them to validate this point.

15.This sounds very similar to Heidegger’s dif-ference as the site for the sendings of Being, but which is itself not Being or Derrida’s Khōra

(Derrida 1993).

|